One hundred years ago, a war of surpassing violence and cruelty ravaged the world. What Winston Churchill imagined as “a glorious delicious war” turned out to be something that beggared adjectives meant for sunsets or chocolates.

The Great War, later called World War I, murdered soldiers in the mud at the Western Front, in the Alps, in the Russian steppes and in primitive aircraft in the skies—”half the seed of Europe, one by one,” in Wilfred Owen’s words.

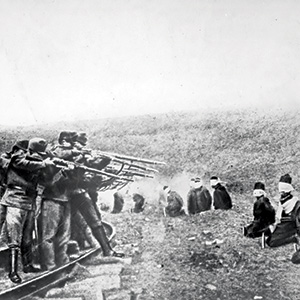

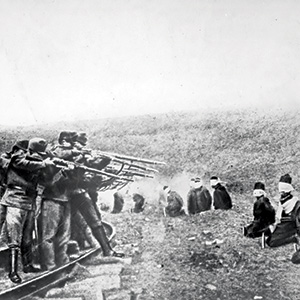

Lesser known heroes of the conflict were the pacifists who stood up to club-wielding mobs, secret policeman and the threat of the firing squad. Alleged defenders of civilization and freedom, the British executed three times as many of their deserting soldiers as the Germans did and 4,000 censors were on the royal payroll. Field Marshall Haig gave the war correspondents captain’s uniforms and these embedded reporters left out everything that mattered. Meanwhile in prisons, conscientious objectors told their stories on a newspaper made of lavatory paper.

Historian and Mother Jones co-founder Adam Hochschild documented these lesser-known stories—and more—in his 2011 best-seller To End All Wars; on April 6, he will appear at Stanford as a guest lecturer for the university’s free series commemorating mankind’s greatest follyÉ so far.

“This terribly destructive war remade the world for the worst in every conceivable way,” Hochschild says, sitting in a cafe in Berkeley. “Twenty million dead, if you count civilians as well as military. But what interests me is the battle between the people who thought it was a noble and necessary cause, and those who thought it was madness and would not fight.”

War museums are crammed with the relics of battle, but little historical traces of the people who risked so much working for peace remains. “Even looking hard for photos, I was never able to find photographs of an anti-war meeting.”

Facing the possibility of execution, an anonymous objector quoted in David Boulton’s Objection Overruled felt he was passing on a truth which the world would one day treasure as “a most precious inheritance.” We legatees should remember Eugene Debs, who got a million votes for President while imprisoned for resisting the war, and Kier Hardie, a coal miner turned member of parliament, who wore himself out in fighting the war. On one day in Germany, thousands of munitions plant workers walked off their jobs. Women’s rights suffragettes—were a part of the rebellion.

Resistors ranged from the unstoppable Lord Bertrand Russell, to the less remembered railway worker and journalist Albert Rochester, a wounded corporal jailed for writing a letter describing the front to the Daily Mail. In prison, Rochester was witnessed the execution of three soldiers condemned for desertion. As it happened they were members of a special “Bantam Batallion” made up soldiers too short for the original draft; the British Army had lost so many soldiers that they were making room for troopers who were 5’4″ and under. Hochschild recalled, “I made contact with Rochester’s grandson, and found the articles he’d written in some pretty obscure places, such as the newspaper of the British Railway Union for the 1920s.” Rochester himself survived the war because of intervention from his powerful union.

We think of all peaceniks as gray and mild, but among them was a lion-tamer turned writer named John S. Clarke. “I like writing about the British,” Hochschild says. “In this country we’ve got lion tamers, and we’ve got war resisters, but we don’t have people who do both.” Maybe on-the-job training taught Clarke to sharpen his claws on others. Hochschild reprinted some journalism worthy of Ambrose Bierce. In a comic eulogy, Clarke imagines the funeral of Alex Gordon, a particularly demented government agent provocateur. Gordon’s testimony of a curare-dart plot to kill Prime Minister Lloyd George caused an activist named Alice Wheeldon to be sentenced to prison for 10 years. Clarke suggested that the obsequies for Gordon would occur inside the grave, “And maggot worms in swarms below/Éshedding tears of bitter woe/É mourn—not eat—a brother.” As they say, WW1 was slightly redeemed by the poetry it created.

Hochschild’s next book is provisionally titled A New Heaven and Earth; it’s about American participation in the Spanish Civil War. I asked where he planned to be for the 120th anniversary of the armistice in 2018. “I hope someone, some group, will be commemorating the resistance,” he says. If I can find something like that kind of commemoration, that’s where I’ll be.”

Adam Hochschild

April 6, 7:30pm, Free

Cubberley Auditorium, Stanford