Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center may be best known for its extensive Rodin collection and, consequently, Romantic humanism, but its Modernist holdings are also considerable, and—with the acquisition of Dotty Attie’s cross-disciplinary cultural commentary Sometimes a Traveler/There Lived in Egypt (1995)—Postmodernism has now invaded the Greco-Roman sanctum.

Attie came to prominence in 1980s New York with the Pictures Generation—media-savvy artists satirizing capitalist culture, American-style, and even our national shibboleth of individuality, which they saw as socioculturally formed and reinforced. (Nowadays, of course, Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine and Barbara Kruger are international art stars, collected by top capitalists—such are the ironies of cultural rebellion, commodification and deification.)

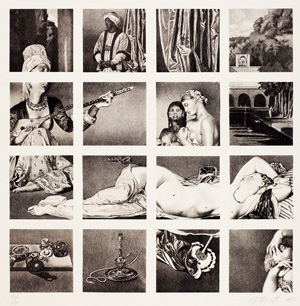

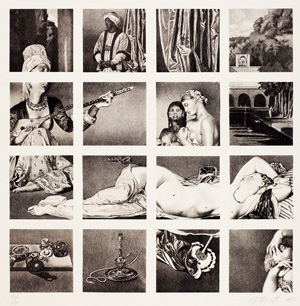

Attie’s piece is a grid of 16 square-format crayon lithographs, in black-and-white, depicting details from two paintings by that paragon of neoclassical tradition, J.A.D. Ingres. Odalisque With Slave (1842) and Turkish Bath (1862) show, with some erotic heat (considering Ingres’ bloodless, austere reputation), the sexual chattels of the Near East, with harem slaves relaxing in poses of refined, voluptuous languor—a theme explored by Delacroix and Matisse, as well.

The artist’s appropriation of Ingres follows similar resamplings of Bronzino, Vermeer and Courbet. Art in America sees her goal as achieving “a narrative effect to suggest the almost illicit excitement of the viewer in the act of perception. Beyond its actual story content, Attie’s narrative paintings imply a deeply voyeuristic gaze whose target is trapped in a small rectangle of painted matter.” Alas, we are all Orientalists, projecting our fantasies into cultures that we can then hypocritically condemn. Assisting this implicit denunciation of the viewer (male or faux-male) is a textual overlay—a kind of mocking voice-over. (“Resistance and Refusal Mean Consent” is one ironic mantra that Attie has used repeatedly to indict rapists’ delusions.)

In the portfolio of 16 prints that accompanies the framed print grid, Attie tells a humorous tale of cuckoldry from The Thousand and One Nights (accompanied by her own stage-whisper asides) that involves an unhappy wife, her lover and a gossipy parrot, which is abused by the illicit couple in such improbable ways that its credibility with the comic-victim husband is destroyed. Although Attie uses Richard Burton’s risque 1885 English version of The Husband and the Parrot, Galland’s 1704 French version, famously bowdlerized for mixed company, is on display here—choose your poison.

Dotty Attie: Sometimes a Traveler/There Lived in Egypt

Shows through June 16