Manuel Neri’s muses are equal partners in Assertion of the Figure, an exhibit of the Bay Area artist’s work at Stanford’s Anderson Collection. He’s primarily known as a figurative sculptor, one who represents the female body.

While the curators aren’t downplaying his talent, they’re also openly crediting Joan Brown, Makiko Nakamura and Mary Julia Klimenko as the inspirations behind the sculptures and paintings on display.

Collectively, the exhibit makes the argument that a female muse isn’t just a passive subject for the male artist to objectify. Rather, she’s a collaborator. You feel each woman’s presence in the work, side by side with the man who shaped it.

Neri and Nakamura (sometimes referred to as Makiko) met in Carrara, Italy. He established a studio there in order to access marble from those famous quarries. She was the model for Makida III, a large, marble head with unseeing, absent or closed eyes. While her lips and nose are cleanly defined, there are concave, smoothed out spaces where the eyes and ears should be. Neri has applied green and pink paint to accentuate the marble’s natural veins.

These washed-out splashes of color adorn her face as if she’s been marked with aboriginal tattoos. From the back, her hair is made into an impeccably polished round bun. Makida III is situated in the middle of the gallery and she compels your attention.

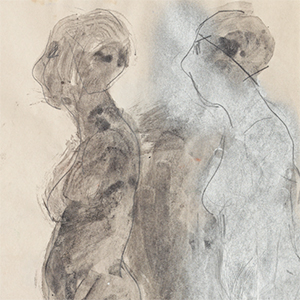

The six figures in the ink-on-paper series Japanese Dancer Study (Makiko) are even more cryptic. These midnight black sketches and smudges are inspired by the human form but missing flesh and bones. They’re apparitions returning from some dark place, an unhappiness the artist glimpsed in his model’s expression or profile. Neri isn’t just recreating the shape of Nakamura’s skull or her body’s tremulous outline, he’s depicting the unknowable self, the one that turns the viewer into an estranged outsider.

Several of Neri’s paintings are included in Assertion of the Figure. Some of the watercolors, like the ones in the K.C. series, mimic the visual effect of an oil or acrylic impasto. Brushstrokes collide in violent layers of muddy greens and putrid reds creating silhouettes of anonymous, faceless souls. Joan Brown Seated in Studio 13a black ink and graphite drawing from 1958anticipates the central sculpture in the exhibit. Neri made Joan Brown Seated (1959) out of aluminum and painted her white with yellow glazes, otherwise known as his “alborada patina” (alborada meaning “dawn” in Spanish). Does knowing that Neri and Brown were married for a time influence the impact or meaning of the work?

The drawing features a more recognizable woman, with a round belly and shoulder-length, stringy dark hair. He gives her a right eye and a nose but then blends the cheek down to the neck without making an attempt to draw in the lines of a mouth or her lips. The sculpture, though, is even more denuded of human features. She has no hair or arms and sits on her pedestal, knees up and almost reaching her naked breasts. Unlike Makida III‘s high-gloss finish, which confers a chilly, divine status on the bust of Nakamura, the woman in Joan Brown Seated sits ravaged by life or fate, or the place where they both converge. Neri leaves the traces of his rasping tool on her body and face so that we can see her scars. She is beautiful, vulnerable and pitiable because we can see the internal damage he’s made visible on the surface of her skin.

Mary Julia Klimenko has been Neri’s model for the better part of four decades. In a 2001 interview with the San Francisco Chronicle the artist said, “Her angularity made my work very sculptural.” Here that quality is represented in nine maquettes, the scale models for the larger series Mujer Pegada (Spanish for glued or attached woman). In the series, the body is not separated from the material out of which she’s being carved. If you’d walked into the museum without knowing who the artist was, you might mistake them for artifacts salvaged from an ancient place like the city of Pompeii or the Parthenon.

Neri strands each figure on her own, a stone woman among the ruins. His work strips the specificity away from their particular bodies until they become something else the muse made solid in plaster, bronze and willowy veins of marble.

Assertion of the Figure

Thru Feb 12

The Anderson Collection, Stanford

anderson.stanford.edu