CARTOONIST Art Spiegelman’s new book MetaMaus is a series of literary concentric rings around his Pulitzer Prize–winning graphic novel Maus, which was originally published between the years 1977 and 1991.

These are conceivably Spiegelman’s last words on the subject. He has been drawing “tragics” (as opposed to comics) about the Nazi death camps ever since a three-pager in a San Francisco underground comic in 1972. His main source was his own father, Vladek Spiegelman, a prisoner of both Auschwitz and Dachau. (Spiegelman’s mother, who also made it out alive, later committed suicide in 1968.)

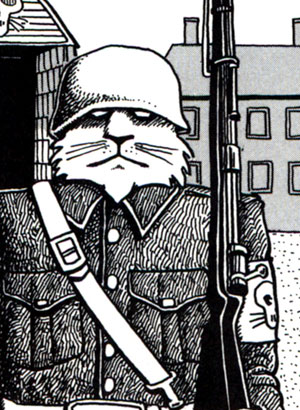

Trying, like so many undergrounders, to free cartoons from the realm of Disney, Spiegelman portrayed the Holocaust as a cat-and-mouse game. In the two parts of Maus, the Nazis are cats and the rounded-up Jews are mice.

Spiegelman began this project when there wasn’t really much business in shoah business. Today though, no comment is necessary under one of his drawings in Maus, critiquing what the artist calls “Holokitsch.” We see a starved, shocked concentration camp prisoner holding an oversized Oscar.

How to communicate this inconceivability? In this collection of transcriptions, documentation, memoirs and interviews—not to mention the sheaf of rejection letters Maus received from a dozen publishers—Spiegelman chronicles his life of being a historian of something people would prefer not to remember. “No one wants anyway to hear such stories,” says his father.

“Maybe everyone has to feel guilty! Forever!” Spiegelman satirically imagines shouting at an interviewer.

Due to its dozens of translations, easy accessibility and frequent assignments in schools, Maus may be the only book a post-literate generation reads about the extermination of the European Jews.

The good news is that the beginner couldn’t ask for a better guide than MetaMaus, which has much better mapping: guides to further reading, along with contemporary illustrations by Nazis and camp prisoners alike. MetaMaus is a fine primer on how to create a graphic novel, with Spiegelman’s early sketches linked to final versions to show the artistic choices he made. More importantly, now we can actually listen to Vladek Spiegelman’s voice (on the accompanying CD) and read a transcript of his interviews.

Of course, the younger Spiegelman tries to refute some of the charges against him. Two reoccur frequently. One is how he used (or perverted) the age-old funny-animals format, which goes back to Aesop. Spiegelman’s Poles are pigs, but in the Warner Bros. bestiary, Porky was always the settled one, the farmer and the straight man. The animals aren’t of any one type. Civilian German cats are less fanged than Spiegelman’s Nazis. No American who knows his historical slang can object to the U.S. soldiers as literal dogfaces. Spiegelman also seems sensitive to those who thought he equated his own personal angst with the sufferings of his father.

Rereading Maus, one gets a fresh exposure to the old man’s abrasiveness. Who was Vladek typical of, except himself? His ingenuity was the reason he was the one among thousands who lived. Vladek was an escape artist, a salesman and a conniver, with poetic syntax (he knew five languages, but his English was idiosyncratic).

He was a racist and a self-aggrandizer. And he was a scavenger. Vladek embarrasses his son by salvaging some wire from a garbage can. Yet this incident makes a subtle lead into a story of the camps—of one Mandlebaum who prayed to God for a length of string, because he couldn’t guard his soup and hold up his sagging uniform pants at the same time.

As one of the ones who made it back, Vladek was never entirely sure that the Nazis might not return. And he wanted to pass his prison education to his child. Many would have run away from such lessons for good.

Critics have pointed to this cartoon version of Art Spiegelman as a bad son, angry, neglecting and neurotic. In fact, such a slaved-over and haunting preservation of a father’s history shows nothing but a son’s devotion.

MetaMaus

By Art Spiegelman

Pantheon; $30