Wooden crates, produce boxes and discarded coffee cups are some of the unconventional materials used as canvases in “Our Connection to the Land.” The exhibit reminded me of what we can all easily ignore: There’s a group of fieldworkers who’ve spent hours, days or weeks harvesting the fruits and vegetables we buy at the market.

These narratives endow their subjects with a specific sense of individuality. We can see that they’re just trying to make a living like everybody else.

In his work, Narsiso Martinez confronts the state of being carelessly unconscious ofor indifferent towhere our food comes from. “My motivation for representing farmworkers is really to shine a light on their plight,” Martinez said in a 2018 interview with the Long Beach Post. He has also worked in orchards, at times, in order to earn a living, so he isn’t acting like a voyeur or an artistic tourist.

For the mural-size Always Fresh, Martinez reclaimed and flattened produce boxes. Using complex layers of ink, charcoal and gouache, the artist created a triptych. When you stand up-close to the connected boxes, you can make out patches of the original branding. A smiling orange with dancing feet waves at you. An apple exudes the arc of a rainbow and a tiny cloud. But from a few feet away, the dense foliage of trees darkens most of the background.

On the left half, four workers pour fruit into a bin. None of them are as happy and carefree as that dancing orange. The right half depicts another group of four workers taking a break in the orchard. A crop duster flies in the sky above them. Linking the two halves at the center is the framed head and shoulders of a worker, inside of a golden crest like a president on an American dollar bill. Rendered in black and white, this gender-ambiguous figure looks like a masked avenger. Their face is covered in a bandana. Their eyes are hidden behind dark goggles. We concentrate our gaze on this hero’s image and recognize their worth.

In two other companion pieces, Francis and Viviana, Martinez flattens and mounts Starbucks coffee cups, trimming the edges off and collaging them so that they fit onto square canvases. He then arranges 14 of them into the shape of a cross. Each one is an ink and charcoal portrait of a fieldworker standing over a plant that hangs with the heavy burden of ripe coffee beans. The white coffee cup with the green logo takes on a different meaning altogether when you see the faces of the people who’ve plucked the beans from their stems.

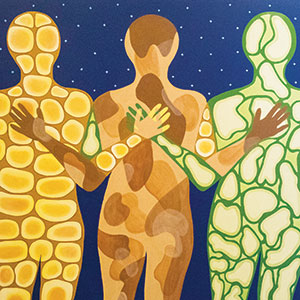

More abstract is Suzy Gonzalez’s acrylic painting, Three Sisters. Three faceless figures stand next to each other, arms linked, staring into a starlit night. Each body carries or contains a random internal pattern, one with yellow orbs, one with brown oblong shapes and the last with a variety of green blobs. They could be archipelagos of misshapen vegetables that have been absorbed into their blood streams. On an adjacent wall, similar shapes recur in Gonzalez’s Revolutionare they, after all, different varieties of tubers, beans or nuts? Has she freed them from the three sisters so that they can float freely, unconsumed, in a space of their own?

Abiam Alvarez’s sculptures concentrate on morbidity (Box of Cantaloupes and The Skulls of Those Who Picked Them) and decay (Broken Picking Unit). They’re as weighty and fraught with meaning as Karen Miranda Rivadeneira’s series of black and white photographs of human bodies and foreboding landscapes.

In her series “Mujeres,” which is not included here, Arleene Correa Valencia erases the faces of street food vendors but paints their wares in bright tropical colors. Those women are between places, both seen and unseen. With Cesar Valencia and Wilber Valencia, Correa Valencia comes up with an inventive way to make use of shipping crates, staining the wood and then painting fieldworkers onto them. Because of the spaces between the planks, the portraits double as a commentary on the idea of a wall. The fieldworkers look like they’re behind and moving through or beyond the bars that contain them. Like the mujeres, Cesar and Wilber are also finding their way out of limbo, even if they’re only partially in view.

Our Connection to the Land

Thru March 15, 2020, Free

MACLA

maclaarte.org