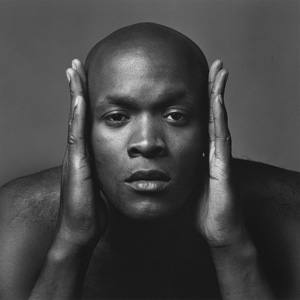

ONE HUNDRED and three black-and-white portraits hang with precise tastefulness at eye level, subtly lit, meaningfully annotated and experientially revelatory.

One hundred and three squarish rectangles, mostly a little taller than wide, all of moderate size, modestly framed, offer few high-contrast shadows, melodramatic compositions or outlandish angles, but rather flattering head-and-shoulder shots of people against a neutral background from a traditional perspective at middle distance: each subject’s head and chest occupies most of the rectangle. A few faces spill over the edges, shot achingly close.

With its new show, “Robert Mapplethorpe: Portraits” (traveling from the Palm Springs Art Museum), the San Jose Museum of Art deploys to perfection its well-designed gallery space in presenting this sequence of images in a syncopation that draws the viewer into one work and then along from portrait to portrait in an ever-deepening appreciation. Despite the consistency of size, tone and composition, each is a singular biography. In totality, “Portraits” illuminates a time and a place—and the man behind the camera.

At first glance, these images seem to fall within the glamour-portrait tradition that helped create the star system of Hollywood’s “golden age” in photographs by George Hurrell, Laszlo Willinger and Clarence Bull. Their subjects were not humans, however, but dramatically lit, fastidiously retouched icons eternally ready for their close-ups.

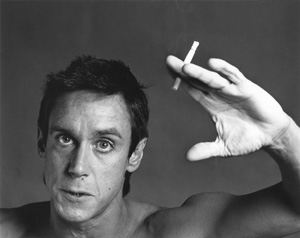

Mapplethorpe, too, aimed to flatter those who sat for his camera; however, his subjects were not products of the star factory but instead were determinedly individualistic denizens of the hectic and hard-edged world of celebrity and notoriety that was New York, the epicenter of the art world in the 1970s and 1980s.

Actors and artists, socialites and sex workers, bankers and bikers: the objects of Mapplethorpe’s portraits were so used to being photographed that the camera seemed simply an extension of their ego. Perhaps in the course of the sitting, something in each of them moved toward and merged with the camera—the dumb witness to this performance of themselves to the world. The eyes that look out to the viewer are looking at a mirror, not posing but caught at an in-breath of recognition. After all, the man behind the lens was not a stranger but one of them.

An Irish Catholic boy from Queens propelled by an innate and relentless quest to create something distinctly his own, Mapplethorpe became the most extreme version of himself and lived hard on that shiny sharp edge within a world that exalted edginess and extremity. He died from complications of AIDS in 1989 at age 42. His work had already been celebrated for more than a decade.

On book covers, center spreads and billboards, many of his portraits merged with the history of his subjects—a luminous Susan Sarandon with her daughter looking out with loving trust; a relaxed David Hockney sinking into his own composition; Annie Leibovitz uncomfortable on the other side of a camera; Andy Warhol, his white hands and trademark white fringe both shielding parts of himself. These images were familiar beyond the art world, part of the published texture of the decade.

Within the more discreet milieu of galleries and museums, Mapplethorpe was celebrated also for his dramatic images of flowers and nudes—bodies of work exhibited worldwide and which sold for huge prices. Shortly after his death, however, Mapplethorpe became notorious when the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., refused to hang its scheduled National Endowment of the Arts funded “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment” due to the homoerotic and sado-masochistic content of the work. The incident ignited an international scandal about publically funded artwork, threatened the existence of the NEA and provoked countless public and private discussions of censorship and the line between pornography and art.

This is not the Mapplethorpe revealed in “Portraits.” Rather, as Gordon Baldwin states, this is the body of work that is his most lasting legacy.

Robert Mapplethorpe: Portraits

Through June 5