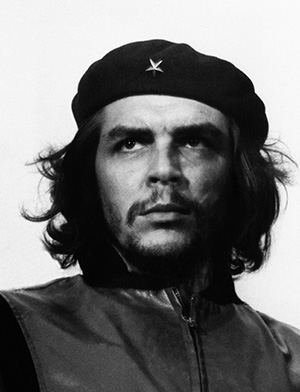

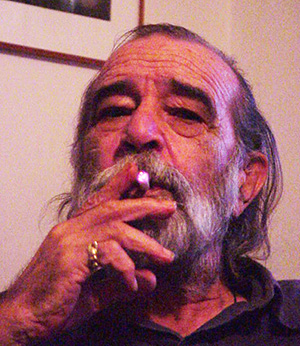

On a rum-soaked Havana afternoon twelve-and-a-half years ago, I asked Alberto Korda about the collection in his back room. After his midday nap, the 72-year-old photographer would ritually greet guests in his modest apartment’s living room, which overlooked a small bay on the capital city’s coast. Between shuttered windows hung Korda’s portrait of Che Guevara with a searing, distant gaze beneath a star-adorned beret, the blown-out version of which is slathered on walls throughout Cuba and screened on t-shirts worldwide.

If a visitor expressed interest in buying a photograph, Korda would disappear for a few moments and emerge with black and white enlargements, often shots of Fidel and Che golfing, fishing or smoking cigars, or chatting with Ernest Hemingway. He’d exchange the prints of the anti-capitalist icons for stacks of U.S. currency and say, between draws on a cigarette, “When I die, these will be worth a lot.”

“I prefer that they remain worth less,” I’d reply. I’d initially been fascinated with the way he manipulated images and had grown fond of a man who was warm and vulnerable.

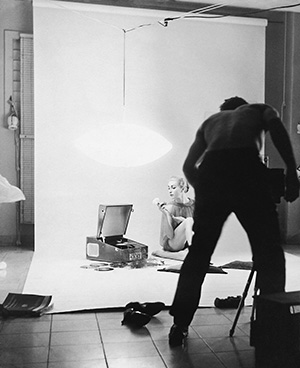

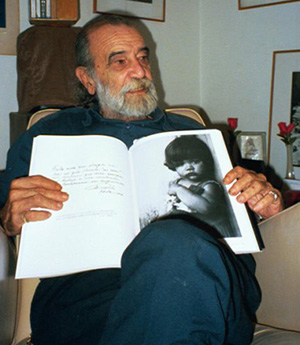

In a spare bedroom, Korda kept stacks of photographs that he didn’t show to the souvenir-seeking tourists and Che-idolizing journalists who showed up at his doorstep. There were elaborately staged fashion shoots and graceful nudes that seemed a world apart from the guns, green fatigues and macho poses he documented as the court photographer to the Cuban revolution. He told me about the women in the photographs. “This was my wife,” he said, as he stared at one of the photos. He lifted another, and said it was of his longtime girlfriend. There was a story behind each photograph.

Six weeks later, Korda died of a heart attack during a trip to Paris. In the inheritance drama that followed, the prints found their way to other countries and collections, and the negatives that survived remain locked up in a state ministry. While a few fashion shots had appeared as counterpoints in shows of his political works, there had never been a comprehensive showing of Korda’s pre-revolutionary photography until the one that’s hanging in a gallery at Foothill College’s Krause Center for Innovation through December 6.

The Los Altos Hills exhibit may not completely answer the question of whether Korda was simply a technically adequate propagandist who lucked his way into fame by capturing the most reproduced photo of the 20th century—or if he was Cuba’s Avedon, an artist who could spot a image that would permanently burn an imprint into the viewer’s brain cells.

A pragmatic chameleon, Korda captured the opulent displays of wealth and excess during the high point of Havana’s mob-controlled casino days, then glamorized the austere militarists who closed the gambling palaces and executed enemies of the revolution.

Korda said he was transformed into a supporter of the campaign to eliminate social injustices when he photographed La nina con la muneca de palo. His ex-wife, the model Norka, recalled that moment during her visit to Santa Clara Valley last week. “I was there when he took this photo in Pinar del Rio. I was the one who saw the girl. He was taking pictures of me next to a deer, and I saw in back of him a girl using a piece of wood as her doll. I whispered to him: ‘Alberto don’t scare her, but behind you there is a little girl using a stick with a little skirt as her doll.’ It was very sad. … The girl was very poor, she was in a poor peasant’s house, a bohio, and she came out of the house when she saw us, some strangers in the area.

Norka says “he definitely was motivated against injustice and the poverty he was exposed to as a photographer.”

She describes Korda as a paradox. “He was a capitalist who lied to Fidel,” she says.

Before his death, I had asked Korda about the photo and the socialist revolution’s failure to solve Cuba’s extreme poverty while Cuba’s leaders lived like millionaires. “He lives like a head of state!” Korda thundered in Fidel’s defense and blamed the U.S. embargo for the island’s economic woes. He vouched for Castro’s character and stayed loyal to him until the end. Castro carried the photographer’s casket when he was buried at the Colon Cemetery, the same one where Korda had snapped the famous Che photograph 41 years before.

Korda’s friendship with Fidel Castro hadn’t saved him from a state enforcement action when he was accused of being a pornographer for taking nude photographs of his models.

“That was the reason they closed the studio and confiscated everything,” Norka recalls.

“It was a great injustice. None of Korda’s pictures were pornography.”

“It was terrible because they accused him of being an antisocial criminal, an immoral pornographer. It was the last business confiscated in Havana in 1968. …Those were difficult years in which the revolution went after the homosexuals and others. Now it is different. Some of the people who were repressed then have been rehabilitated, and some are important and respected people and artists.

“I remember when Alberto came to my house and told me that he lost all my pictures, and he asked me for forgiveness. He asked his friend [Raul] Corrales, another great photographer who was well connected. They talked to Celia [Sanchez, Fidel Castro’s confidant and former lover], and her office rescued all the political pictures. But I don’t know the destiny of other pictures.

“The government confiscated his entire studio, his property, including all our family pictures. The government took all the negatives, the pictures of the time when my children were born, the pictures of me. The government confiscated his entire business and our pictures, but when Fidel called him, he began to work for Fidel. He profited from the same government that took everything from him.”

“I know that some people are selling pictures of me on the Internet, including nudes, and profiting while I am surviving on 10 dollars [a month] with six dogs. Do you know how much my pension is? Only 200 pesos. And now, after an increase, only 240 pesos. Almost 10 dollars.”

Last Wednesday, Norka celebrated her 75th birthday in Los Altos Hills, one of the world’s wealthiest communities, and told her story, while an exhibit celebrating her beauty graced the walls. The restored photographs might provide some small income for Cuba’s greatest model of her time, during the island’s brief moment in the international fashion industry.

The exhibit, and the stories that underlie them, tell a fascinating story of wealth and poverty; truth and propaganda; love, sex and betrayal. That a local college professor pieced together this moment in history to give audiences here the first glimpse of some beautifully curated and recently unearthed images is another improbable addition to the life and legacy of Alberto Korda.

Check out the first time ever in the world these photos have been displayed together at Korda Moda at the Krause Center