Last week, I was trying to make room for Nathan Myhrvold’s six-volume Modernist Cuisine series. The 40-pound cookbook to end all cookbooks expanded my culinary book collection to about nine linear feet and forced me to displace some guacamole bowls and cheese-serving plates to free up a third shelf.

My expanding collection of physical books is clearly counterintuitive in the digital media age. It may be even more irrational given that no one actually reads cookbooks, and I rarely cook with them. Yet, for some reason, I just had to own the $500 cookbook considered the most impressive example of the genre ever to roll off an offset press.

Like most things that can be digitally accessed, locating a recipe in a cookbook is inefficient. I developed expertise in limoncello production with a few web searches. And I converted three bags of organic spinach into Mark Vetri’s famed spinach gnocchi when I found an online scan of his book.

I pasted some screen shots into the Evernote syncing app and tediously paged through the paragraphs on my smartphone. The gnocchi, after two days of spinach processing, turned out beautifully green and bouncy, though not quite as intensely spinach-y as the ones I sampled at Vetri in Philadelphia before a Nine Inch Nails concert. (I think Mr. Vetri saves the real recipes of his signature dishes for patrons of his eponymous restaurant.)

Nonetheless, I bought Il Viaggio di Vetri, and it arrived a few days later. I ran my fingers softly over the embossed title, dropped out of a Tuscan orange background above a black-and-white photo of four laughing chefs. Inside there are ample photos of sensual rare meats, cannoli orgies and dripping strands of pasta curled around fat pieces of lobster, along with Vetri tricks, such as reducing 50 pounds of onions for eight hours to make six servings of white truffle onion crepes. That pretty much explains why it’s easier to validate one’s credentials as a foodie by displaying a good cookbook collection than it is to actually spend time crying over onions.

Over the years, I’d pieced together a modest collection of cookbooks by California chefs like Alice Waters, Wolfgang Puck, Joyce Goldstein and Jeremiah Tower, some of them autographed as souvenirs of visits to their restaurants. I’d more recently added Charlie Ayers’ Food 2.0, one of the rare books by a Silicon Valley chef—until David Kinch publishes his—and purchased the display copy of Michael Mina’s cookbook at Arcadia before his Cinequest visit.

But the collection needed further updating. It was clearly missing some Keller. So I plunked down $50 for The French Laundry Cookbook (Artisan, New York). The large-format book is filled with images of hands caressing chunks of butter, pink sliced figs and a precariously cantilevered pastry curl atop mascarpone sorbet. Keller also has another 11-by-11-inch sous vide tome that I have yet to crack, and I’m looking forward to doing so.

Keller’s work straddles the art vs. science divide nicely, offering aesthetic warmth, graphic minimalism and advanced technique.

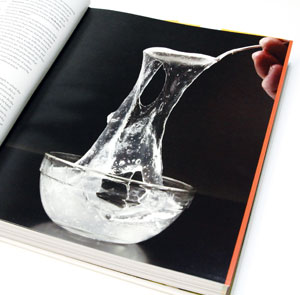

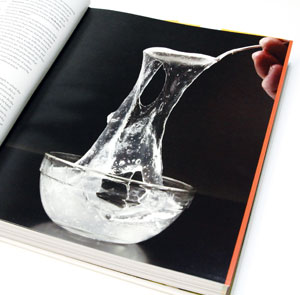

Myhrvold’s magnum opus, on the other hand, is about as sensual as a college anatomy textbook. The cover is blindingly white with typefaces reminiscent of 1980s-era architects’ brochures. The book smells like a bad varnish factory in China, where the volumes were printed and, except for the beautiful photographs, the design is unimaginative, with titles (“Sublimation and Deposition’) that are generic and uninspired.

Sections are devoted to equipment like blow torches, centrifuges, rotary evaporators, food sealers and immersion circulators. While it offers the best technical information on gels, foams and celebrity chef secrets like making edible dirt, there are whole chapters on buzz killers like food pathogens.

Catalan chef Ferran Adria’s El Bulli: 1998–2002 is the Latin counterpart to Modernist Cuisine. While hailing from the same school of scientific cooking, the focus is on the results, rather than providing a how-to manual. It comes in a chalk-streaked charcoal box that looks like it was damaged in shipping, with the truck backing over it after it fell off the lift gate. Inside one finds page after page of photos with barely any text, a food voyeur’s fantasy come true.

One day, I hope to properly read these books and attempt some recipes, hopefully without blowing up my kitchen like a meth lab. In the meantime, I’m happy to be a collector.

I know I’m not alone. Psychology Today has explored the “psychological obsession with culinaria’ and “prurient interest in erotic photographs of elegantly presented dishes,’ as a pseudo-psychological form of aberrant behavior. One writer jokingly suggested “treatment for people who are obsessed with cookbooks, cooks and other things culinary.’

Do you find yourself spending too much time at Sur La Table, staring at exotic kitchen implements or having erotic thoughts in the cookbook section of one of the few remaining bookstores? Those may be warning signs. Seek help. Or give in.

Ferran Adria, Juli Soler, Albert Adria; Ecco, 2005

By Thomas Keller with photographs by Deborah Jones; Artisan, 1999

II Viaggio Di Vetri: A Culinary Journey

By Marc Vetri, David Joachim and Douglas Takeshi Wolfe; Ten Speed Press, 2008

Bulfinch Press, 2006

By Nathan Myhrvold with Chris Young and Maxime Bilet; The Cooking Lab, 2011