THE FLOURISH of strings fans out into an exquisite patter of notes as sharp as icicles. Then a sad violin takes up the refrain. The music is age-old yet fresh, accessible yet mysterious. The sound is a mélange of musics. It’s made up of the essence of jazz: that blend of Civil War–surplus brass instruments, of Armstrong and Ellington, of African roots and snazzy New York Jewish songwriters. As played by guitarist Django Reinhardt, violinist Stéphane Grappelli and the Quintet of the Hot Club of Paris during the 1920s and 1930s, it was a music that enraptured the world.

Jan. 23 is the centenary of the birth of Jean Reinhardt, dit Django; the date will be celebrated on Jan. 25 in Santa Cruz with a tribute concert at Kuumbwa Jazz Center. Later, on Feb. 28, the San Jose Jazz Winter Series will present the Hot Club of San Francisco in a salute to Reinhardt and Grappelli.

The Hot Club was the main jazz conduit between the New World and the Old World. Historian and bassist Brian O. Torff, who will be playing at the Kuumbwa show, calls the members of Hot Club “the first important European jazz musicians.”

Among the local fans of Hot Club–style jazz is Jim Nadel, artistic director of the Stanford Jazz Workshop. “Django was very significant in the development of jazz guitar,” Nadel comments. “He was one of the first people to play a stringed instrument percussively. He brought a fresh lyricism to the guitar that hadn’t been heard to that point, and he also brought a cross-cultural influence to jazz—quite common today, something new then. He blended European music with the Gypsy-style impressionist qualities of Ravel and Debussy.” (“Maybe Debussy comes closest to my musical ideal,” Reinhardt once remarked.)

The Stanford Jazz Workshop is in its 38th year as a nexus of residency and jazz camps for younger children; it will put on its own Django tribute in late July, with guitarist Julian Lage, Victor Lin on violin and Jorge Roeder on bass.

The music is worth celebrating. According to Nadel: “The Hot Club was a departure for jazz. Prior to this band coming together, everything had been focused on brass and African American percussion. But the Hot Club were string-instrument players, and they still swung strongly. There was a lot of forward motion mixed with the lyricism. No room for cliché in Django’s music! And he was a fascinating character. He couldn’t read music: in fact, he couldn’t read at all. There are great legends about him, great lessons for persevering through adversity and limitations.”

Reinhardt’s sound and iconic image have turned up on soundtracks, been referenced in literature and inspired Woody Allen’s film Sweet and Lowdown. Further afield, there is even an open-source web application called Django.

A prime for information on Django’s life is the biography by Charles Delaunay, a journalist and the Hot Club’s promoter. The book seems a bit lordly in the way it characterizes the Romany people as wild children, but the figure Delaunay paints seems real.

Reinhardt was a big man physically, an avid, sometimes ruinous gambler, a flamboyant dresser, “a despot at home” with his women. Grappelli once said that Django was fascinated by the gangsters in American movies.

Reinhardt never lived with a real roof over his head until he was age 20. When he was 18, the caravan that Django shared with his pregnant wife caught fire, badly injuring him and paralyzing two of his fingers. Later, like Jerry Garcia, Reinhardt flummoxed the world by playing better then men with complete hands.

After his recovery, Django moved from the banjo-guitar he had previously played to a standard guitar. Eventually, Reinhardt played a bespoke guitar, with an extra-wide fretboard. Reinhardt used the first cutaway guitar, with a scalloped body to enable him to play the highest notes up the neck.

His instrument had a specially shaped sound hole—a sideways D like a cartoon frog’s mouth—to make the bass notes thunder; it was about as loud as an acoustic guitar could be. “Like a church on Sunday morning,” one guitar maker says of the Reinhardt-style Selmer-Maccaferri guitar.

The Road to India

Torff has been in our area previously, playing with George Shearing and the San Jose Symphony. He will be among the performers celebrating Django’s centennial with a tour that leads from Kennedy Center in New York to the small yet sacred Kuumbwa Jazz Center in Santa Cruz. The ensemble in this tribute show includes guitarist/violinist Dorado Schmitt and his son Samson, along with renowned violinist Pierre Blanchard and ace accordionist Marcel Loeffler.

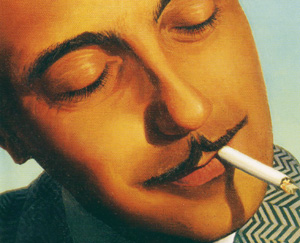

Schmitt is one of the most celebrated players of jazz manouche, Gypsy jazz. He’s a striking figure who resembles Django, with his debonair ‘stache, pointed chin, high cheekbones and half smile.

“Dorado is a great technician on the instrument,” says Torff by phone from New York, “but he’s not overly technical. Not every virtuoso makes contact with the audience, but he does. I love working with Dorado. He’s one of the best guys I’ve heard. And he’s got his own ideas, he’s doing his own thing.”

Schmitt appeared in key scenes in Tony Gatlif’s 1993 movie Latcho Drom, playing his guitar at the annual May festival honoring the Romany’s patroness, St. Sarah la Kali, whose statue stands in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, a small French town where the Rhône hits the Mediterranean.

Gatlif made an important point in his unnarrated documentary. The source of jazz manouche can be traced a long ways away, both in time and space; it’s a road that leads all the way to India’s Rajasthan. One can hear India in the Hot Club’s notes: the same roots can be felt in the throb and drone of Hungarian violin and in the repetition of Andalusian arpeggios.

Over the years, Gypsy jazz went in and out of style. Grappelli weathered the rock-drunk 1960s playing violin at the Paris Hilton. When he made his 1973 London appearance with guitarist Diz Disley, it revived interest in the Hot Club’s music and led to a Carnegie Hall date. (For that matter, Dan Hicks and his Hot Licks brought newbies to the sound through the manouche-ish hit “I Scare Myself.”)

Manouche jazz never went silent, though. Charles Delaunay noted that the Hot Club’s music could be heard “in the jukeboxes of Texas, in the cinemas of Chile and on the radio networks of Cairo or Saigon.”

“It’s a very joyous, ebullient sound, and people just love that spirit,” Torff says. “Every large city in the world has its own Hot Club today.”

Torff once toured with Grappelli and recalls, “The audience we got were both jazz fans and people who weren’t particularly jazz fans … people drawn not just by the music but by the warmth of the acoustic sound.”

Legends

Torff’s recent memoir, In Love With Voices, is a salty yet humble account of playing alongside luminaries like Dizzy Gillespie and Benny Goodman. Torff also describes the problems and rewards of teaching jazz; he currently teaches appreciation for the music at Fairfield University in Connecticut.

Born in the Midwest, Torff studied at Berklee College of Music and had a turbulent apprenticeship with Harlem pianist Mary Lou Williams. Torff was also apparently the last bassist to play live with Erroll Garner. The bass player writes of his first encounter with the Hot Club music, seeing Grappelli at Carnegie Hall in the early 1970s. Later, he was hired to accompany Grappelli on the road. The partnership lasted an aggregate of four years; the friendship that lasted longer than that.

To prepare to play bass for Grappelli, Torff writes that he “made a desperate attempt to learn every tune ever written in musical history before Meet the Beatles.”

He met Grappelli in a budget hotel room, where the rest of the band was hanging out.

Clad in a bath towel, Grappelli brought out his violin and played “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,” giving Torff a chance to follow. “I do not like rehearsing,” Grappelli added, concluding the audition on the spot.

Grappelli’s career lasted decades, and yet his legend isn’t as bright as Django’s—likely because he didn’t die young. Torff notes, “Grappelli behaved himself and showed up on time, so he didn’t make good copy. He was a natural. It was like watching Michael Jordan, you think, ‘He’s got it—don’t know what it is, but it’s there.’ He was an effortless musician on violin and piano, and I never saw him strain once. I love and respect Django, but Stéphane was an equal master, and you can ask any jazz violinist, and they’ll tell you the same thing.”

One incident about the relative fame of Reinhardt and Grappelli turns up in Torff’s book. “Stéph always had a good sense of humor about … his love/hate relationship with Django … whom he would often have to fetch from a bar or a pool hall just as he was about to perform. Sometimes onstage he would announce to the audience, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, we would like to play a composition by my dear late partner, Django Reinhardt.”

“Then,” Torff continues, “this charming, dear and grandfatherly elder man would lean over to me with a smile on his face and whisper in a voice only I could hear. “That …”

Shall we insert here the French word “con”? I think so.

The SetList

Django died early, at age 43, of a stroke. The last “Djangology” recordings, made 1949–50 and released as The Indispensable Django Reinhardt, collected almost all of the 50 tunes recorded by Django, Grappelli and some Italian session musicians. It shows the musicians conversant with bebop. Django’s late-period experimentation with an electric guitar also suggests that he was looking toward the future. Says Torff, “Django was always seeking something else. Unfortunately, some Djangophiles imagine him encased in ice like a woolly mammoth. He wasn’t like that. Nothing’s pure; we’re all seeking new influences.”

The Django tribute at Kuumbwa, Torff notes, is “probably going to include ‘Minor Swing’ and probably ‘Nuages.’ In addition to the typical Hot Club thing, we’ll do some original tunes, likely Dorado’s song ‘Bossa Dorado.’ ‘Souvenirs’—ah, we’ll probably be doing that.

“At some point, there’ll be a bass feature—likely the song ‘Manhattan Hoedown’ I did with George Shearing. Every show is different. We don’t call the tunes, and we don’t have a format, just like it was with Grappelli. Whatever is happening in the dressing room, we’ll bring it to the stage.”

In concluding, Torff urges jazz students to go back to the roots of the music, to spend time with the still-living innovators of jazz: “There’s something unique there. And that’s not to say there aren’t some American musicians who play it well. But jazz comes from the black Baptist gospel church, and you’ve got to go back to that, or you’ll sound like a voyeur, a tourist.

“It’s the same thing with the Gypsy jazz. It’s deeply imbedded; it is their blues. Dorado Schmitt is one of those people who did live on a caravan and did start playing a guitar at about 3 years old around campfires. The audience will be able hear those traditions in Dorado and his son Samson. And I’m sure Samson will teach his son, and it’ll go on and on.”

THE DJANGO REINHARDT FESTIVAL takes place Monday (Jan. 25) at 7 and 9pm at Kuumbwa Jazz Center, 320-2 Cedar St., Santa Cruz. Tickets are $25–$28. (831.427.2227)

San Jose Jazz Winter series presents the Hot Club of San Francisco performing the music of Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli on Sunday (Feb. 28) at 2pm at the Improv, 62 S. Second St., San Jose. Tickets are $28–$30. (408.280.7475)