WAS THIS the bus that launched a million trips? Paint-smeared and packed to the gunwales with wiseacres, the bus chugged across the hidebound United States in 1964, a land summed up by a visionary of its time, Robert Crumb, in words just as descriptive of the state of our nation in 2011: “I must maintain this rigid position or all is lost!”

The bus was a pioneer wagon headed to the pacemaker city of New York. Aboard were frontiersmen. Some were literary scions, some party-seeking funzos, some honest job seekers. This, then, was their journey.

The partially locally filmed documentary Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place reconstructs footage of the famous jaunt. Working with historical details and recollections of the surviving passengers, directors Alison Ellwood and Alex Gibney (Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room) have assembled the legendarily tangled footage of the trek of the bus named Furthur.

It was a rolling ark outfitted and christened by the man who gave LSD its nickname “acid.” He was Stanford graduate student and internationally famous author Ken Kesey, of The One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and The Sometimes a Great Notion fame.

San Jose’s Candace Lambrecht, the former wife of Kesey’s confederate Stephen “Zonker” Lambrecht, remained close to Kesey through the years, connecting with him every time he came to the valley. She likes the movie, with a few reservations.

“I’m so glad that it’s finally finished,” she stresses. “In general, it’s a quite well-done editing of Kesey’s film. It’s a worthy effort. The editing is masterful, and the collection of all those comments from Chloe Scott and George Walker and Ken Babbs—it all worked quite well. The limiting of the subject matter to the first bus trip was intelligent, with a few things added to have it make all more sense. Ken’s life is quite vast.”

Lambrecht came from the East. In Oregon, while going to college, she encountered Kesey, and later met her husband through his friends. “I became, in a weird way, part of this tribe. It was one of those tribal things that the ’60s were so good at fostering,” she says.

Lambrecht was never on the bus in question, but she was a Merry Prankster from 1967 on and also saw Kesey’s footage numerous times.

Kesey died in 2001 with this film still a work-in-progress. He sometimes despaired over the project: “Hundreds of hours and millions of feet of jiggly bus footage …” he complained in print, during his attempts to try to weave this interstate home movie into a film.

Road Warriors

Marcel Duchamp said that writing about Dada was like putting together a bomb that had gone off, and the filmmakers’ task must have been similarly daunting. Deposited at the UCLA Film and TV Archives, the original 16 mm film was deteriorating; 100 hours of unsynchronized and unsorted audio on tape made up the soundtrack.

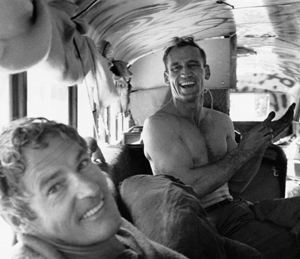

As much a movable convention as a bus, Furthur was staffed with a group of Kesey’s pals he dubbed “The Merry Pranksters.” As it traveled from California to New York, Furthur became the rolling meeting place between the old avant garde and the rising ’60s rebels.

“We weren’t old enough to be beatniks, and we were too old to be hippies,” Kesey says on the soundtrack.

Kesey’s mission was simple. He and his colorfully nicknamed travelers were taking the long way around America to get to the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City.

Furthur itself was an aged, gutted International Harvester. No great shakes as machinery, it ran out of gas and started fritzing immediately. Magic Trip mentions that it took 24 hours to get the 36 miles from Kesey’s place in La Honda to San Jose on the first leg of its journey.

As it rolled toward Los Angeles and beyond, Furthur had a celebrity at the wheel. Fresh out of a two-year prison sentence for the heinous crime of possessing a marijuana cigarette was the fabled Neal Cassady.

Kesey outfitted the bus with a gas generator and some audiovisual equipment: 16 mm cameras, a tape recorder and a large sound system. Little did he realize that his inability to sync up all of these devices would keep this material from being unveiled as a full-length motion picture in his lifetime.

San Jose’s John Cassady, son of Neal, explains the problem: “The 16 mm cameras had their own battery sources, but the 1/4-inch tape players were powered by the bus’s generator system. Whenever father and Ken would accelerate the bus, their voices would speed up and sound like this” [amphetamined Mickey Mouse] “and when they’d slow down, it’d sound like this.” [Johnny Cash on Seconal]

When I talked to him, John Cassady was on his way to Santa Cruz for his third viewing of the film. He’s been working on his own book-length memoir of his father: “I’ve got stories that’ll curl your whiskers.”

Clearly, he’s delighted by Magic Trip‘s footage. One reads a lot of memoirs, documentaries and so on resounding with moaning about the tragedy of having ’60s hippie parents.

Cassady is different. “Are you kidding? My upbringing was the complete opposite. I had an idyllic childhood, I felt like a rock star. I relish every memory. To this day, it’s like, don’t get me started. If I’m onstage, talking about my dad, it’s ‘Katy, bar the door!'”

Cassady adds, “I’d wanted to go on that trip. I was 13, but my mother had no sense of humor and thought I should go to high school instead. Seeing this film, though, I’m thinking, ‘Mother knows best!'”

Though Cassady had seen Kesey’s uncut film over the decades, there were parts he hadn’t, such as the scene he considers the film’s funniest: his father’s expert finessing of a highway patrol officer, partially with double talk and partially by chance (a juicy sneeze on the proffered driver’s license). The lawman eventually gives up and leaves to go look for other reprobates.

The voyage is animated a la mode in the cute blunt-scissors animation style popular in Fox Searchlight romantic comedies: a cut-out bus and vintage postcards uncrumple over a map of the United States. The real thing was a one-bus circus coming to town, parti-colored and blazing with counterintuitive messages: “Weird Load” and “A vote for Barry is a vote for fun.” The latter was a motto referring to the paleo-Republican presidential candidate of 1964.

Magic Trip shows that the journey wasn’t all fun and games. There’s an LSD freak-out in Houston occasioned by the not just electric but high-voltage orange juice in Furthur’s larder. We see a snubbing by LSD guru Timothy Leary, who didn’t want to deal with these California yodelers. The pranksters get a similar cold shoulder from Kerouac himself, at a crowded party in a New York City apartment during a record heat wave. He’s hunched over, nursing his surliness with a tallboy of Bud.

Finally, the New York World’s Fair itself—what a trip. It’s “Mad Man” Don Draper’s own dream of an America always moving forward. It was the home of Futurama, the cradle of “It’s a Small World” and “The Happy Plastic Family.” It was, as people said of Disney’s Tomorrowland, a broken promise of things to come.

Recollections

Candace Lambrecht was not on the bus, but her late former husband was. “I called him Stephen, and I called him Zonker,” she says. “I met him at the Grateful Dead’s house. He was such good friends with [Merry Pranksters] Mike Hagen and Ken Babbs.”

She would like to set the record straight. “My nits are minor but substantive. I’ll mention the use of actors’ voices for the people who weren’t involved in the reconstruction, such as Gretch [“Gretchen Fetchin’, a.k.a. Paula Sundsten] and “Generally Famished” [Stanford philosophy professor Jane Burton]. These lines were plot drivers; they had to do something to move the narrative forward. I understand some people are deceased, and some wouldn’t want to participate. That was then; this is now. But the use of the actors felt inauthentic, and only someone like myself would say that. It ever so slightly tarnishes the presentation.”

Lambrecht also hopes the historical context of the bus ride is clear. Take the footage of the Pranksters stumbling across a segregated beach at Louisiana’s Lake Pontchartrain.

According to Lambrecht, “It presents them as young people who didn’t know what was going on at the time. They realized after a while that there was a bit of a threat in the air, that they were doing the wrong thing. It comes across too flip in the movie, as if the Pranksters weren’t conscious of civil rights. If they were chased out by the black people, there was several layers of that: first that they were intruding on their space, secondly if you caused trouble down South in those days, everyone was going to get into trouble. The film makes it look as if they were naive frat boys from the West Coast who knew nothing.”

Acid Indigestion

It took the charisma of Kesey himself to hold this voyage together.

“I was the prettiest little boy you ever did see,” Kesey recalls in the film. He was a University of Oregon student who was accepted into Stanford’s writing program; he was also an Olympic wrestling team hopeful.

He was perhaps comparable to Henry Rollins in thickness of neck and compellingness of talk. And if he wasn’t straight-edge like Rollins, he wasn’t a big imbiber. By the time of Kesey’s fateful encounter with LSD he had only been slightly drunk once.

At Stanford as part of the prestigious graduate writing program, Kesey signed up for a government psychiatric test of a promising new purported migraine cure called LSD-25. (This cover story was, as it sounds, a lie. The CIA was conducting the now-infamous MKULTRA experiments; they hoped some sort of chemical weapon or truth serum could be derived from the drug.)

Magic Trip is at its most interesting when it could have been the most cute. Here are actual vocal tracks of Kesey’s interviews with doctors, recorded during this first acid test. The directors and Karin Fong of the animation company Imaginary Forces are creative at coming up with visuals to suggest the time-melting qualities of psychedelics: the clocks going octopus; the colors shifting.

This sequence is contrasted with the more ridiculous official version of what happens to the user of psychedelics, familiar to all fanciers of kitschy public-service films: hippies leaping off of cliffs (“I can fly, I can fly! Aieeeeee!”), and Jack Webb’s rock-faced TV policeman Sgt. Friday sternly dealing with a day tripper.

Later, during a job at the graveyard shift at the Menlo Park Veteran’s Hospital, Kesey wrote One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

The book is a classic, as people who have never read it know. They know it’s a classic because they have watched the 1975 movie, and they understandably enjoyed the spectacle of Jack Nicholson going bonkers.

The book is a different beast, and Kesey harbored a valid point against Milos Forman’s movie version. Magic Trip claims Kesey never saw the movie even though he wanted to sue Berkeley-based producer Saul Zaentz. Kesey objected to the R.D. Laingian “Society is crazy; crazy men aren’t crazy” vibe of the film.

“Being crazy is painful,” Kesey noted.

Into a sinister, monochrome mental hospital, like Peter Pan into the nursery, comes a savior. The renegade red-headed gambler and lay-about R.P. McMurphy, with Tolstoy-hard hands, earned the Distinguished Service Cross for escaping from a Korean POW camp. Now he’s just one more internee under the hands of Big Brother’s surrogate Big Nurse.

Randall McMurphy is an idealized version of Kesey himself, wide and friendly, a stirrer-upper using comedy and theatrical gestures to make the oppressed to think for themselves. He was in some ways a missionary, and there’s something of that mission in what happened to the footage seen in Magic Trip.

After the bus’s return, the footage gathered was projected in 36-hour uncut doses—first at Kesey’s place in La Honda and then at a friend’s house in Santa Cruz in November 1965. Later, at the home of a mysterious local African American San Jose hipster known as “Big Nig,” Kesey and the gang threw an after party for the doubleheader Rolling Stones show at the San Jose Civic on Dec. 4, 1965. Here was the first occasion at which Kesey’s friends’ rock band the Warlocks tried out their new name, the Grateful Dead.

Journalist Tom Wolfe was on hand, as he reported in his book Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test: “Cassady rapping, Paul Foster handing people weird little things out of his Eccentric Bag, old whistles, tin crickets, burnt keys, spectral plastic handles. Everybody’s eyes turn on like light bulbs, fuses blow, blackness … minds scream, heads explode, neighbors call the cops.”

Kesey wasn’t through with our area; he came back several times, once in 1993 with the latest model of Furthur to visit with the staff of the local alternative newspaper and to give them a little spin around the city. As Metro publisher Dan Pulcrano wrote at the time:

Kesey turned left at Santa Clara Street and circled the arena, calling it “the largest Airstream trailer in the world.” On the box office side, Kesey spotted a militarylike formation of palm trees, a signature of the tightly wound redevelopment look of the 1990s and said, “Watch this.” With a flourish, he thrust his open hand out the bus window toward the columns of palms and yelled, “Stay!”

That was later. Ultimately Kesey, the LSD and the uncut film came to San Francisco, better known as a vortex for the psychedelic life. Hundreds, then thousands, saw and transmitted the vision of a nomadic life, of redeeming absurdity in the face of societal pressure.

“I’ve been on the road with Kesey several times,” John Cassady says, “And it was a cacophony of absolute mayhem—sometimes it didn’t really make sense but that was his whole point. I don’t know what his point was but whatever it was, I think he achieved it.”

Followers of these charismatics wrapped themselves in the colors of a flag that, as Kesey said later, represented the right to burn itself. Colonies sprung up in the cities of America. One aspect of what we remember as the 1960s had begun.

“Kesey was always on the cutting edge of everything,” Lambrecht says. “And you get that from this film. He reiterates how very American they were, these college people from middle-class families of the 1940s and 1950s. But he was always at the right time, the right place: just as it was for Cuckoo’s Nest, the right book at the right time. Kesey was writing real lit.”

Damn Hippies

Magic Trip successfully has it both ways. You’d have to be a bit of a dead soul not to envy the trip. Still, there are counterpoints. As Mark Christensen wrote in his recent unauthorized biography Acid Christ, there’s not much leeway between Kesey’s phrase “You’re either on the bus or off the bus” and “My way or the highway.”

Maybe the most personally annoying detail caught in Magic Trip is the sequence of the trippers spilling toxic paints in a marsh so they can watch the colors float before their LSD-soaked pupils. One can be sometimes riled by the amateur-hour style of the footage, or the tendency of the camera to make a wet-T-shirt contest out of a swimming scene. One takes into mind Jane Burton’s comment on the bus: it was “Exactly the opposite of a pleasure palace.”

As limited in scope as the voyage of Furthur was, it foaled imitators by the thousands—imagine the armadas of VW buses. Even the Partridge Family was piloting its own Mondrian-ized Furthur on TV within six years.

What was meant as a serious gesture of embracing and enlightening America became, at worse, a fashion. The gospel was spread by the glittering prose of Tom Wolfe. With some occasional reservations, Kesey liked Wolfe, in counterpoint to the old law that every public figure hates the journalist who made him famous.

Lambrecht sums up: “Everyone is going to interpret things in their own way, but there’s some of the original intent of the Pranksters in Magic Trip. That’s why I like it. It’s up to those of us who are still around to put a proper spin on it.

“It’s a good thing that this movie has come out so late. It’s a social documentary—that’s what it always should have been. It’s not the beginning or the end of any world, just an exploration—part of a continued exploration and evolution of consciousness. What resulted was a baseline paradigm shift.”

MAGIC TRIP: KEN KESEY’S SEARCH FOR A KOOL PLACE

(R) Opens Friday at Camera 3 in San Jose.