Stay Hungry | Selling a Vision | Animated Character | Hits & Misses | How I Got Dissed By Steve Jobs

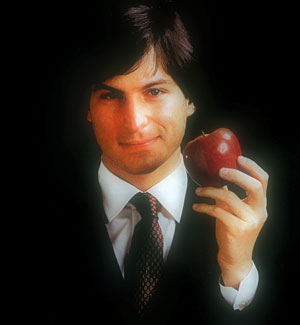

STEVE JOBS and I were precisely the same age, born within a few weeks of each other, on different sides of the Santa Cruz Mountains and, as it would turn out, into vastly different worlds and cultures.

I met him—and his partner Steve Wozniak—on various occasions during the early years of Apple, as Jobs and I had a mutual friend with whom he attended Reed College, in Portland.

The world of computers didn’t much interest me. I was, at heart, a radical Luddite. I was neither enamored with, nor intrigued by, his vision. Indeed, I thought Jobs and Woz were nothing more than computer nerds, far too driven and ambitious for my taste. I much preferred the earlier incarnation of the southern San Francisco Bay region—as the Valley of Heart’s Delight—than I did as Silicon Valley, with life seemingly speeding out of control, away from the slower rhythms of nature.

When Jobs was leading Apple during its astonishing first decade of success, I was still cutting fish on the Santa Cruz waterfront—with the same wood-handled fillet knife that generations of men in my family had used. In graduate school, I refused to use a personal computer, and I pounded out all my papers and articles on a manual Underwood Standard made in the 1930s. I was living my life in opposition to the so-called Apple revolution.

I lost the digital battle, of course. I resisted as long as I could, but by the 1990s I began working on my first Apple Macintosh. With that, I was hooked. Much of my life today—and even more of my family’s—revolves around technological apparati in which Jobs and his colleagues at Apple had a hand in creating.

Parables for Living

A little more than six years ago, in June of 2005, I was diagnosed with a very advanced and aggressive form of colon cancer. A short time later, during my early and difficult treatments with radiation and chemotherapy, someone sent me (by email) a copy of Jobs’ now rather legendary commencement speech at Stanford University, which he delivered on June 12, 2005, precisely two days before my diagnosis, and two weeks after my own father had died of the same disease.

Timing is everything. I read Jobs’ speech several times during my own difficult journey with treatment. Very suddenly, Jobs interested me in a way that he hadn’t when we were younger. Our once seemingly disparate universes had converged.

Jobs’ speech was broken into three short “stories,” as he called them, a trio of parables for living in the modern world.

In the first he talked about his early foray at Reed College. I hadn’t realized that he had dropped out after six months and then stayed on, auditing classes (“dropping in,” as he called it) for another year and a half, before returning to Los Altos to start up Apple in his parents’ garage.

It was an aspect of the Jobs r–sum– I wasn’t familiar with—living on the couches of friends, collecting bottles for their deposit money, going for Sunday meals at the local Hare Krishna temple—and I was taken by the fact that at an early age, he had given into his “curiosity and intuition.”

His second story focused on his much publicized firing by Apple in 1985, when he was 30 years old. Jobs acknowledged the devastation of that dismissal. But he also, over a period of months, rediscovered the “love” and “passion” that had motivated him a decade earlier. Being fired was actually a form of liberation. Steve Jobs was freed to become Steve Jobs again. “The heaviness of being a success,” he declared, “was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again.”

But the part in the speech that interested me most was his public declaration that a year earlier he had been diagnosed with cancer. I had heard about Jobs’ diagnosis—very vaguely—but knew nothing of the details.

Jobs announced that he had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and that his doctors originally told him it was both “incurable” and that he had “no longer than three to six months” to live. It is devastating news, of course, hard to grapple with and sort out at first, but gradually, one is forced to confront one’s mortality. I know that first-hand: I was originally told that I could have as little as six weeks to live. It’s a powerful confrontation.

As Jobs noted, one’s world narrows immediately. “It means to try to tell your kids everything you thought you’d have the next 10 years to tell them in just a few months,” he declared. “It means to make sure everything is buttoned up so that it will be as easy as possible for your family. It means to say your goodbyes.”

All pride and external expectations and fear of embarrassment, he observed, “just fall away in the face of death.” He was right. They do and they did. Although he didn’t note it at the time, it is another form of liberation—much more radical that his dismissal from Apple had been two decades earlier.

Jobs’ cancer journey, however, then seemed to take a radically different path than my own. According to his third fable, his oncologists performed a biopsy on the day of his diagnosis and discovered that he had a “very rare form of pancreatic cancer that is curable with surgery.” His encounter with his own mortality had lasted less than a day. “I had the surgery, and I’m fine now,” he told the students with apparent confidence. “This was the closest I’ve been to facing death, and I hope it’s the closest I get for a few more decades.”

Steve Jobs was a man of big dreams and colossal visions. I have no idea what his actual diagnosis was, the precise details that make all the difference. Cancer, I have discovered is, like snowflakes. No two prognoses are exactly alike. Perhaps he needed a sense of a full “cure” in order to continue pursuing those grand dreams.

But for me, my dance with cancer has led me not to gaze too far into future, to entertaining the luxury of contemplating “a few more decades.” It has forced me to live in the moment, the here and now, to appreciate the gift of the present.

If I could have added a footnote to his speech at Stanford, it would have been to remind students that the moment is all we have. It is all any of us have.

That said, Jobs clearly understood the chronological—and biological—parameters of our lives.

“Your time is limited,” he said, “so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice.”

He concluded by reminding students of an exhortation he had read on the back of the last Whole Earth Catalog in the mid-1970s: “Stay Hungry. Stay Foolish.”

What a wonderful thing to tell young people on the verge of going off into the world. Words to live by, certainly. And, as it turns out, words to die by as well.

Santa Cruz writer and filmmaker Geoffrey Dunn’s most recent book is The Lies of Sarah Palin: The Untold Story Behind Her Relentless Quest for Power (St. Martin’s).