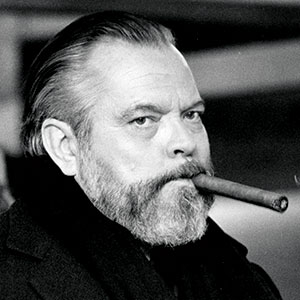

The merry prankster, the profound tragedian. The professional guest, the misunderstood exile. He was pitied, parodied—”All’s well that ends Welles.” Moonfaced and inconstant as the moon, Orson Welles directed Citizen Kane and adaptations of Shakespeare, Kafka and pulp fiction.

“Perhaps I bewilder people by being at once the esthete, the intellectual and the vulgarian” Welles said. The bewilderment over Welles’ legacy continues up to his centennial this May.

In his wise, rapid documentary Magician, Chuck Workman sums up a director known for shadowy masterpieces about death and the wasting away of promise. Hard stuff for your chipper American film student who expects sunshine and redemption, yet Welles’ ought to be a lodestar to the indie filmmaker of today.

Workman interviews all the right people: actor/biographer Simon Callow, biographer Joseph McBride and critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, as well as Welles’ two surviving daughters and his companion Oja Kodar.

Workman’s best decision was to not spend too much time on Kane, by just noting its greatness and moving along. It’s treated as one chapter—and not the most important—in Welles’ 30-plus years of filmmaking. This ultimate hyphenate was distracted by the other aspects of life. “I don’t take art as seriously as politics,” Welles says at one point. At another: “I don’t enjoy acting as much I should.”

Workman is maybe best known for the montages of classic movies and actors that are played during the Oscars. Welles was a filmmaker uncommonly attuned about the importance of editing. He has here a first-rate editor shaping his life—from his days as a talented prodigy to extemporized films made in his last years.

In his failures to get along with studio management, did Welles flop out of the American studio system? Did he cut and run on movies that he could have fought for? It’s an outrage Welles’ work was so frequently butchered. And as Rosenbaum notes elsewhere, it’s a shame that Steven Spielberg squandered thousands on a collectible “Rosebud” sled—”Steven, we burned it!,” Welles chortled—when he could have invested in Welles’ cinema. But this birthday celebration honors the wealth of art Welles left us.

Magician suggests an alternate approach to Welles’ history—more than just beating the old drum about Welles failings and martyrom. Everyone knows the story of the clown crying on the inside. Is there a reversed version, the tragedian who enjoys life? The “exile” of Welles was a successful dodging of the commie-hunting McCarthyites. He gourmandized, and scrounged up money acting in what Welles called “king parts.” As an example, Workman chooses a snippet of Man For All Seasons, with Welles in crimson as Cardinal Wolsey—an old cat having a formal audience with a church mouse (Paul Scofield’s Thomas More). Europe provided inspiration in Mr. Arkadin (1962) and Othello; Welles describes here the sleepless night that drew him to the Gare D’Orsay’s illuminated clocks, and thus straight to his film of The Trial (1962).

As a maker of film noirs like Touch of Evil (1958) and The Lady from Shanghai (1948) Welles had few peers. As a Shakesperean, he was supreme. Welles’ 1967 Chimes at Midnight—just discovered in 35mm print form—is waiting for new viewers once the lawyers are paid off and the screenings become authorized; the film was sold in more pieces than the play Springtime for Hitler. Welles’ 1948 Macbeth is wounded by impoverished sets, but fatally injured through costumes. A funny hat is one thing, but a funny crown is unforgivable. Workman’s excerpts convince me I missed something, and that I must go back to Macbeth for a rewatch.

Was Welles a thwarted child prodigy, dissipating himself when he should have been finishing his Merchant of Venice? Rather, when acting out Falstaff on The Dean Martin Show, wasn’t Welles presenting the groundlings with an easy entry to the vastness of Shakespeare: pointing out the popular, crowd-pleasing essence of something eternal?

Magician shows us Welles’ gravestone. Like his character, Harry Lime, he seems to still be at large. What was said of Jean Vigo by one of the French director’s associates could be said of Welles: “He’s still here.”

Magician

94 MIN

PG-13