THIS Thursday at the Tech Museum in downtown San Jose, ZER01 officially launches a new series: ART/TECHNOLOGY: In Conversation. For the debut episode, Rick Rinehart of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive will moderate “The Future of Play,” a conversation with IDEO’s industrial designer and toy inventor, Joe Wilcox, along with interactive digital artist, filmmaker and researcher Scott Sona Snibbe.

At press time, the event was filled up, but it will broadcast live via Ustream, where anyone can tune in and participate.

The tag-team duo of Wilcox and Snibbe provide just what the doctor ordered when it comes to engaging conversations such as these. Wilcox invents toys at IDEO, a multi-award-winning global design firm with offices in Palo Alto. Before that, he worked as an industrial designer for NASA and at MIT’s Aero-Astro Lab.

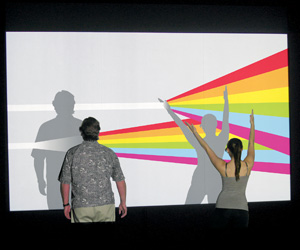

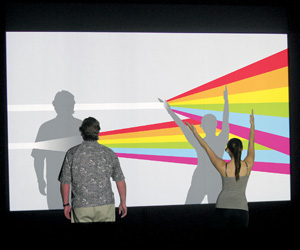

Snibbe is all over the place. He evolves as a media artist, filmmaker and researcher in social interactivity whose creative output infiltrates a wide variety of galleries, public spaces and portable devices. At Adobe 15 years ago, he contributed to After Effects. His films have shown worldwide. His interactive installations tend to engage the public in a playful fashion. He has written academic papers, seen his work featured in many art catalogs and now produces interactive experiences for the iPad.

During the conversation, several potential questions and strands of thought could reveal themselves: What is play? Why is it important? What makes something playful? Is play an activity, a game or a state of mind-being? How and why is it useful in the creative process, the design process or the invention process? Why do children naturally seem to get it, but adults have to think about it? Will the concept of play become co-opted and go the way of tired cliches like, “innovation”? Should the Tech Museum of Innovation change its name to the Tech Museum of Play instead?

For example, Snibbe says that “play” is a proper context in which to place his own interactive installations and iPod projects. The work isn’t meant to hang on the wall in a museum under lock and key; rather, he wants to engage all participants. While giving a high school lecture, he once asked students to define sculpture. One of them answered: “Something you can touch if the guards let you.”

“That’s in a way what defines my work,” Snibbe explained. “Letting you touch it, letting you engage it, letting you experience it. It’s so sad that the things in art museums are really meant to open up our souls, but because we put the lockdown on them, it’s diminished our capacity in that way. That’s why I make interactive art—it is completely open to people to play, to be social.”

In fact, “art and technology” almost seems too all-encompassing of a blanket term to wrap around this discussion. “Art and technology” in and of itself is nothing new, really. Both art and technology have existed forever, as long as humans have existed. Leonardo da Vinci was an artist and a technologist, for crying out loud.

“I think it’s a little more interesting to get into the specifics,” Snibbe said. “A lot of people are into art and technology, but it’s an amorphous, free-floating thing—they just like the idea, maybe they like to hack—but this panel is about something specific. It’s about people’s interest and capacity for play. Like, what role does play have in everyday life for people, why are they willing to pay for it, what does it mean in the commercial sphere and the nonprofit sphere in art. It’s a very specific topic. That’s why I like it.”

Play is conversation. Play is experience. Play is directly interconnected with creativity, happiness and the flow of ideas. It must never stop.

“Some of the most brilliant people I’ve ever met have been very, very playful,” said Snibbe. “If you clamp down on the play side of yourself, you essentially diminish your capacity to be creative and open. And that’s really what play is.”

The Future of Play

Thursday, 6:30pm