Even COVID-19 will not stop local filmmakers from elevating the ignored voices of San Jose history.

Over recent months, Naglee Park-resident Cotton Stevenson spent a huge amount of time interviewing several alumni members of the Good Brothers, the groundbreaking African American fraternal group that emerged in downtown San Jose in the mid-to-late 1950s. His 30-minute film, gloriously lo-fi and home-movie-like, was scheduled to premiere at the Antioch Baptist Church at Seventh and Julian streets a few weeks ago, until the coronavirus made it clear that people shouldn’t be gathering.

“Given this pandemic, it was really just not smart,” Stevenson says, speaking with a raspy Southern accent. “There were some people that were a little bit heartbroken, but they all understood. We have something set up for the library in August, which may be back on. It’s not canceled, it’s just on hold.”

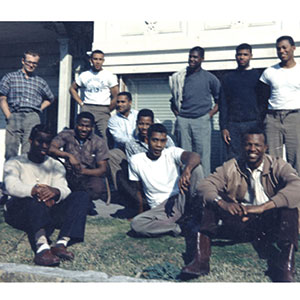

Under the heroic leadership of Chuck Alexander, the Good Brothers operated at 101 N. Fifth St., at the corner of St. John, in a house that still stands. Many in the group were athletes who came to San Jose State University for football or track and field. Predating the Tommie Smith and John Carlos era, many of the men arrived with no money and no idea how to survive day to day, living on their own. During what was still a very segregated time in San Jose, it was uncommon for a black man to graduate, let alone excel, in both athletics and academic study.

The Good Brothers gave men a path to do just that. This was before the Voting Rights Act, before the tumult of the ’60s. So 101 N. Fifth St. was more than just a roof over their headsit was their base, their academic support center and their cultural gathering spot.

Stevenson first met the Good Brothers alumni while working on another documentary several years ago at SJSU. He learned that many of the Good Brothers often returned to San Jose for an annual reunion during the Jazz Festival. He wanted to learn more. They invited him to breakfast at Flames on San Fernando Street, initially to pitch him a documentary about their coaches back in the late ’50s.

But Stevenson wanted to document the Good Brothers themselves: They were the story. Here was a goldmine of ignored San Jose history, especially since the house still existed, as did the Antioch Baptist ChurchSan Jose Historic Landmark #105a place inseparable from the story itself.

The film, available on YouTube, contains interview after interview with several alumni members, who all speak eloquently and poignantly about those difficult times. For example, the men arrived in San Jose only to learn that the college did not offer integrated dorms or housing. They were forced to look off campus, which is how the Fifth Street house emerged as a hangout. Yet despite such hardships, and through their association with the Good Brothers, each young student grew into an adult. They learned ambition, sacrifice, camaraderie, discipline, studiousness and the perseverance to succeed.

Stevenson, who doesn’t drive, needed to interview everyone in their own element because he wanted the film to resemble a gritty home movie. Local sports-historian Urla Hill, curator of now-legendary exhibits about Speed City, became Stevenson’s handler for the project, introducing him to many of the Good Brothers.

“She’s mostly responsible for putting it all together,” Stevenson says. “She schlepped me hundreds of miles, going to and from Stockton, to and from Oakland, to and from Sacramento. She knew who all the guys were, and she knew the Good Brothers’ story inside out. And it was just fascinating, along the way, to meet these people.”

And to this day, the Antioch Baptist Church, founded in 1893, still boasts the oldest local African American congregation. In fact, Alexander’s son Tony still holds court at the church.

“Most of these guys were church people,” Stevenson says, of the interview process. “There was a spirituality about these guys, about the bonding, about the brotherhood. I was like, ‘That’s pretty cool. You don’t get that from Greek fraternities.'”