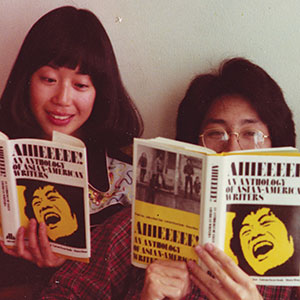

Forty-five years ago, the first anthology of Asian American literature came into the world, a groundbreaking compilation titled, Aiiieeeee!

Just last week, two of the original editorsShawn Wong and Lawson Fusao Inadaappeared at San Jose State University along with poet Marilyn Chin to discuss the literary diaspora’s evolution since the days of that original anthology. All three enlightened the capacity crowd of students with stories from the ’70s, especially what it was like for Asian American writers at that time, how they managed to overcome isolation and find each other, the insults hurled at them by the literary establishment, and all the obstacles surmounted by the subsequent generations. Of all the author events I’ve attended at SJSU for 20-plus years now, this event approached the very top. The history and the stories and were moving.

Wong is back in the news these days due to the controversy surrounding Penguin’s recent power grab over the 1957 novel No-No Boy by Seattle’s John Okada. Concerning the plight of a Japanese-American draft resister in WWII, No-No Boy is now universally understood as the first Japanese-American novel. The original publishing run was only 1,500 copiesthe publisher had it printed in Japan and shipped to the US because the subject matter irked many Americansso by the time Okada passed away in 1971, the book had disappeared into total obscurity. Wong and his buddies discovered a used copy lying around in a bookstore and then contacted Okada’s widow to obtain permission to copyright and republish the novel. Since no other publisher wanted it, Wong had to raise money and republish the book himself in 1976. Three years later, he transferred the rights to the University of Washington Press, who’ve now sold over 150,000 copies of the book over the last 40 years while also evolving into a leading publisher of Asian American literature in general. To this day, No-No Boy has had a dramatic influence on many members of Asian diasporas who wouldn’t have otherwise known that any such thing as Asian American literature existed that long ago.

However, earlier this year, Penguin, claiming No-No Boy was in the public domain, decided to republish the book on its own, without even contacting Okada’s family, thus unleashing a firestorm of controversy. Wong led the resistance, along with Pulitzer Prize winner Viet Thanh Nguyen, who has taught the novel in his classes for years. Thanks to a tidal wave of bad publicity and potential copyright lawsuits, Penguin eventually backed down and pulled its version of the novel from all US bookstores.

Just last week, Wong wrote an essay about all of this for Asian American Writers Workshop, a website I’ve also written for myself, so it was spectacular to see him stand there at the podium in the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Main Library and read the essay in its entirety. His point was the struggle to rescue the novel from obscurity, and keep it in print, was just as important as the book itself. Time has proved him right.

SJSU students filled the room for the Aiiieeeee! event, almost all of whom were not even alive when the anthology first came out in 1974. After Wong read his essay, Marilyn Chin, decked out in a leather jacket with images of roses stitched into it, then took the podium to perform dramatic and hysterical monologues and various poetic forms, including some raunchy haiku that cracked everyone up. Or almost everyone. Some of the students seemed almost afraid to laugh.

Then came Inada with some glorious stories about what it was like to operate as a poet in the late ’60s and ’70s, trying to elevate an Asian American identity when that term was just starting to exist. It wasn’t easy.

All three of them testified to the struggles they had with traditional American professors decades ago, most of whom limited the academic study of literature to the same old canon and who thought nothing worthwhile had been written since 1940 or so. Publishers were even worse.

All in all, the elders arrived, they spoke and they told stories. Let’s hope the publishing industry can finally catch up someday.