Three years ago, I made a solo pilgrimage to a nondescript white building on College Avenue in Palo Alto. Inside, two members of the Sikh Foundation fed me lunch.

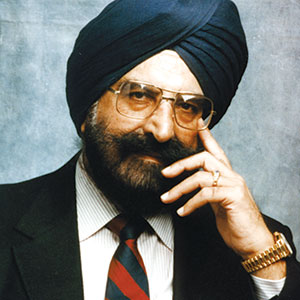

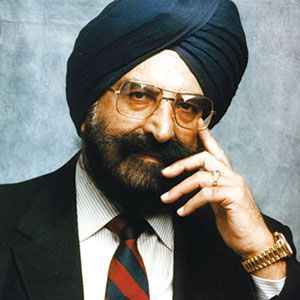

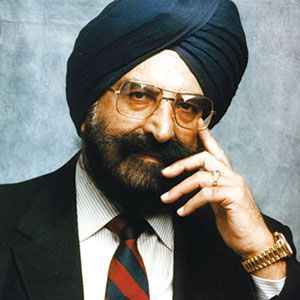

With a belly full of tea and Indian food, I completed the pilgrimage upstairs to meet one of the unsung legends of Silicon Valley: the Father of Fiber Optics, Narinder Singh Kapany. I took up a chair while he sat at his desk before an expansive depiction of the Golden Temple in Amritsar on the wall behind him.

Kapany, who passed away last week at the age of 94, was the first to successfully transmit high quality images through fiber bundles while working alongside Harold Hopkins at Imperial College London. That was 1953. He later coined the term “fiber optics” in a 1960 article for Scientific American.

He was born in 1926 in Punjab, Kapany; graduated from Agra University in 1948; and earned his doctorate from Imperial College London in 1955. Along with his wife, Satinder Kaur, he migrated to the US, eventually working at Rochester University and the Illinois Institute of Technology. Then, in 1961, the couple moved to Woodside, California, where Kapany founded Optics Technology Inc. and took it public in 1967. He was the first Sikh to take a company public in what would later be known as Silicon Valley.

When I visited Kapany in 2017, I did not show up to talk about physics. The Sikh Foundation was about to celebrate its 50th anniversaryKapany started it in 1967and since he was one of the world’s foremost collectors of Sikh art, he was throwing a high-end party at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, where some of his collection was displayed. He was also helping set up a weekend conference of Sikh history and scholarship at Stanford. The breadth and scope of his influence was incalculable.

Until Kapany made connections over the decades, Sikh art had never really cemented a place in the museum circuit. One could find Hindu art, Christian art or Buddhist art anywhere, but not Sikh art. The Sikh Kingdoms tended to get lost in the grander narratives of South Asian history, and via his art collection, Kapany elevated entire stories that even the natives didn’t know.

As a result, Kapany’s collection spawned several groundbreaking exhibits on multiple continents, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, and the Rubin Museum in New York. The gallery he established at the Asian Art Museum is the first permanent Sikh art gallery in the United States.

After meeting Kapany, I could not help but lurk in the shadows for the celebrations all weekend. It was like discovering a missing piece in the jigsaw puzzle of myself. The gala banquet at the Asian Art Museum attracted over 100 high rollers, including current and former parliament members of India, Canada and the United Kingdomall Sikhs. The experience made me want to be an international diplomat, even if I would never pass the psychological and background checks.

Then there was the conference at Stanford, which emphasized Sikh advances in business, medicine and religious studies, but the arts component of the program was over the top. A beautifully esoteric old school European contingent of Indophile museum curator typescharacters straight out of a Graham Greene novelall gave presentations on their scholarship.

Hypothetically speaking, if I wanted to know which descendant of which Punjabi maharajah still claimed provenance of some ancient gold sculpture, or who sold a $90,000 volume of Sikh military paintings to a strange antiquarian bookshop in Marseilles, someone in the room probably had the answer.

It rekindled my love for the international intrigue of art collecting. I wanted to run an importing-exporting business. I wanted to work for UNESCO. I wanted anything to justify the Anglo-Sikh war in my head.

I write this with a laugh, of course, because I have Kapany to thank for it. Like many old Punjabis, he had a loud infectious laugh. His passion for both art, science and philanthropy was a true blessing and we won’t see too many people like him in this valley ever again.