Writing by hand in Urdu, Saadat Hasan Manto (1912-1955) left a legacy that made him one of India’s most celebrated literary troublemakers. With brutal clarity, he depicted the communal violence, paranoia and psychology of Partitionthe blunder from which the country was born in 1947.

Next Tuesday, March 5, Cinequest opens its 2019 festival in soaring fashion, as the illustrious Nandita Das shows up in person to present her film about Manto’s life, simply titled Manto, at 7:15pm.

Many of Manto’s stories do not conform to creative writing teacher requirements in that they don’t have a resolution, an obstacle to overcome or any dramatic transformation of the protagonist. They function more as sketches or vignettes, vividly rendering the despair, displacement and madness of the Partition era. And Manto spared no one.

In 1947, Great Britain arbitrarily carved up its South Asian territory into the separate nation-states of India and Pakistan, before escaping from the scene and unleashing one of the most violent mass migrations in human history. Anywhere between 10 and 15 million people were displaced and forced to leave their ancestral lands on a moment’s notice after being peaceful neighbors for millennia. Countless neighborhoods disintegrated into communal murder, rape and mutilation, with Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims massacring each other, while refugees spent months migrating between the two newly constructed countries. At least one million people lost their lives, all of which exacerbated communal hatred and religious-based distrust, which Indian politicians still exploit to this day. Manto was one the first literary figures to convey the fear, trauma and overt violence caused by Partition, as the resulting chaos unfolded around him in real time.

Throughout his short life, Manto’s stories resulted in him being tried on obscenity charges five times, yet he was acquitted every time. He also went to great lengths to introduce India to Western literature. He translated both Victor Hugo and Oscar Wilde into Urdu. He wrote essays, scripts, newspaper columns and radio plays.

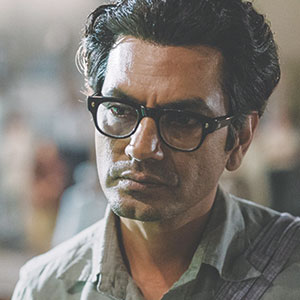

In the film, the legendary Nawazuddin Siddiqui (The Lunchbox) plays the title role in masterful fashion. Although none of Siddiqui’s previous screen roles resemble anything like Manto, Das wrote the film with him in mind. It was the right choice.

When it comes to craft, Manto features scenes from the author’s own stories like “Ten Rupees,” “Khol Do” and “Cold Meat,” all seamlessly juxtaposed with his real-life struggles, which sadly disintegrated into chronic alcoholism amid his displacement in Pakistan. The gritty underside of Bombay had been his beloved milieu, much in the way that Los Angeles was Bukowski’s or Raymond Chandler’s milieu, but then after Partition, as a Muslim, he relocated to Pakistan, after which everything went downhill. He missed the cosmopolitan flair of Bombay and could not comprehend how men could be driven to target even their friends in the wake of Partition.

Throughout the film we get historical atmospherics of Bombay and Lahore, accurate to the times. It’s not a biopic per se, but more like a four-year window into the time when Manto’s world began to crumble. As his mental health deteriorates, he starts hallucinating and begins to identify more with the characters in his stories than the people close to him in real life. His own fiction becomes his reality.

As such, and I won’t spoil it, we also get pieces of Manto’s most famous story, “Toba Tek Singh,” during which the geographic split resulting from Partition is grafted onto the dislocation of the main character’s psyche. In the story, Hindu, Sikh and Muslim lunatics move between asylums in India and Pakistan, much like refugees migrating between countries. Geographic displacement blurs with mental displacement.

To this day, Manto’s stories resonate across India because they predict with brute force the communal, religious, political and gender-based conflicts of a country still battling itself in many ways, with identity politics, caste and freedom of expression often degenerating into to polarized black-or-white discussion with no sense of reality whatsoever. (Sound familiar?) But his predicament, as an artist, resonates far beyond India. He held up a mirror to the violence, prejudice and xenophobia of his time, and often paid the price, both financially and mentally.