Viet Thanh Nguyen | It’s Lit | Kirstin Chen | Ron Hansen | Arlene Biala | Literary Watchlist

Viet Thanh Nguyen won his war with San Jose. It was up to him to finalize the terms of the truce.

Before this could occur, of course, Nguyen heard a voice—well-known and irresistible to dissidents—that demanded release.

So he took to the podium, looked over the dais, and ever-so-gently scolded San Jose’s mayor and council, which, in honoring him for winning the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, had gathered in the very building that erased his parents’ American dream. Nguyen and his brother, just children when the family fled Vietnam and assumed the burdensome mantle of refugees, were just as helpless as adults when their parents were forced to sell their business and see it demolished for a gleaming $343 million City Hall tower and rotunda. Whatever is left of the New Saigon Market lies fossilized at a depth reserved for milk-carton mobsters and earthworms.

This could not be forgotten, or forgiven, without comment.

“I don’t think I did it that harshly,” Nguyen says in a recent phone interview, a lilt of humor in his voice. “But you should not invite me, a writer, anywhere, and not expect a writer to speak his conscience. ‘Oh, you’re inviting me back to give me a commendation?’ Of course I had to point out that City Hall is built across the street from what was once my parents’ store. And this is the kind of history that we need to acknowledge. My high school, Bellarmine, also invited me back to put me into its Hall of Fame. So these gestures on the part of San Jose have been important to me in terms of making me feel like I have reconciled with the city.”

The Climb

Excluding the 140-character buffoonery we wake up to in the present day, Nguyen is currently living in the “ideal years,” he says, referring to the freedom he has to write.

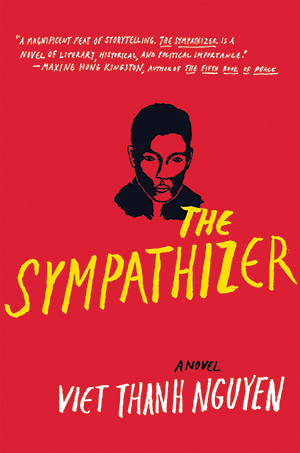

He has the admiration and respect of readers and peers, the hardware of winning a Pulitzer Prize for his debut novel, The Sympathizer. He has reached a literary pinnacle that has no match save for the likewise daunting peak known as Nobel. And yet, the climb has always been the point.

In addition to his duties as the Aerol Arnold Chair of English and serving as a professor of English and American studies and ethnicity at the University of Southern California, Nguyen has toiled for nearly two decades to become the writer he is today. He has published five books—including Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, a work of nonfiction that was a finalist for the National Book Award—and spent the last 17 years working on a short story collection that became The Refugees, released this spring to deserved praise.

“When I embarked on writing the stories that eventually became The Refugees, I went in with a lot of hope and optimism and this naive, idealistic belief that I could finish this book in a matter of a few years,” Nguyen says. “And it didn’t turn out that way.”

In essays, he has acknowledged the creeping doubt every writer feels when a project stalls, and the benefit that can be found in feeling inadequate.

“I think that suffering for the art, suffering for the craft, as unpleasant as it may be, is absolutely necessary to become a writer,” Nguyen says. “It’s through struggle with the form that you learn how to do it. But it’s also good for the writer’s character to go through that kind of an experience, as well. To know that writing is something that is hard-won, rather than easily won. And, hopefully, that provides us with a sense of humility, so that when the rewards do come in we’re able to take them with gratitude and to place them in a context.”

The Refugees features a story titled “The War Years,” set in San Jose and his parents’ New Saigon Market. It includes a telling quote from the character’s mother, who, in being extorted, exhibits the wisdom, strength and resolve of the region’s Vietnamese refugees. She asks her son: “Are you going to be the kind of person who always pays the asking price or the kind of person who fights to find out what something is really worth?”

“My mother never literally said that to me, but that was a lesson I learned from watching my parents,” says Nguyen, whose brother, Tung, a graduate of San Jose High, has gone to become a doctor and professor at UC San Francisco and chair the White House Initiative on Asian American and Pacific Islanders.

Unlikely Hero

In Year 14 of writing The Refugees, Nguyen’s agent recommended he begin work on a novel, a work that has won him untold fans and scorched-earth critics—that is, until the Pulitzer silenced many of the latter. The Sympathizer is not the kind of novel that would normally win praise in San Jose’s deeply anti-communist Vietnamese community. The unnamed protagonist is a half-Vietnamese, half-French communist spy in the South Vietnam Army. The nuance and duality of the character, whose mother was raped and impregnated by a Catholic priest, came relatively easily to him, says Nguyen, who was raised Catholic but rejects the faith, who along with his family fled Vietnam after the fall of Saigon, yet has the ability to acknowledge that not every communist was a monster and not every refugee was a saint.

“For whatever reason, I turned out to be a person who doesn’t like orthodoxy,” Nguyen says. “I was raised as a Catholic, but I’m basically an atheist. And I was raised in an anti-communist Vietnamese community and I wouldn’t say I’m a communist, but I’m certainly much more sympathetic to seeing the world through left-wing perspectives and I’ve read a lot of Marxism. I was raised as American, but I’m very critical of America’s imperial tendencies. So for whatever reason, these perspectives existed in me, so actually it wasn’t difficult to write The Sympathizer. I didn’t have to work against myself in order to create this character. If anything, the character at an emotional level—if not an autobiographical level—is an expression of me, because I do see the world from multiple points of view, most issues from multiple points of view.

“I think the major challenge, obviously, was knowing and is knowing that this viewpoint that my character expresses, and that I endorse, is one that is not popular in any of the communities I talked about: Catholics or Vietnamese Americans or Americans in general. Most communities like one perspective on the world that endorses what it is that they see and are not happy when that perspective is challenged. And I knew that my novel would challenge many deeply held perspectives. When it comes to Vietnamese Americans, their anti-communism is pretty, pretty deep. I anticipated that there would be a lot of people unhappy with me, and that seemed to be the case until the novel won the Pulitzer Prize. All Vietnamese are now very, very proud of me.”

The work is not always easy reading, almost certainly because the insights were not easily gained. Nguyen didn’t arrive in San Jose until age 7, three years after he was taken from his parents and forced to live in Fort Indiantown Gap before moving in with a white foster family in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Reuniting with family offered relief, but also a new window onto how much life had changed for his parents, who worked 12-14 hour days in a downtown that was much more skid row than Santana Row in the ’80s and ’90s.

“I grew up absorbing that and watching those difficulties and those pains,” Nguyen says. “In that sense, that was a shock. … That wouldn’t have been our lives in Vietnam.”

But in the journey of writing his stories, absorbing the pain of his childhood, separating the dogma and propaganda from truth, suffering for his art and balancing it with his work, becoming a husband and a father, and having a community he never felt quite comfortable in welcome him home with open arms, Nguyen has reconciled with a city he will likely never call home again but considers him its native son.

“A lot of it also had to do with just my own tortured adolescence and the particular fact of growing up as a refugee and watching my parents undergo what they went (through),” he says. “I just couldn’t wait to leave San Jose, and on the return to San Jose there would always be this negative association with the city. And I think that in the last decade or so I’ve come around. It doesn’t cause me pain to return to San Jose anymore. I don’t want to live in San Jose, but it’s OK to return. I think that San Jose hasn’t really changed that much for me. I’ve changed.”

And so, he will live.