Without rolling her eyes, Donya (Anaita Wali Zada) wards off her therapist’s questions with a steely reserve.

Dr. Anthony asks about her life in Afghanistan before she moved to Fremont. He asks about her family and what her job was like as a translator for the United States Army. The few facts Donya willingly gives up are detached from her emotions.

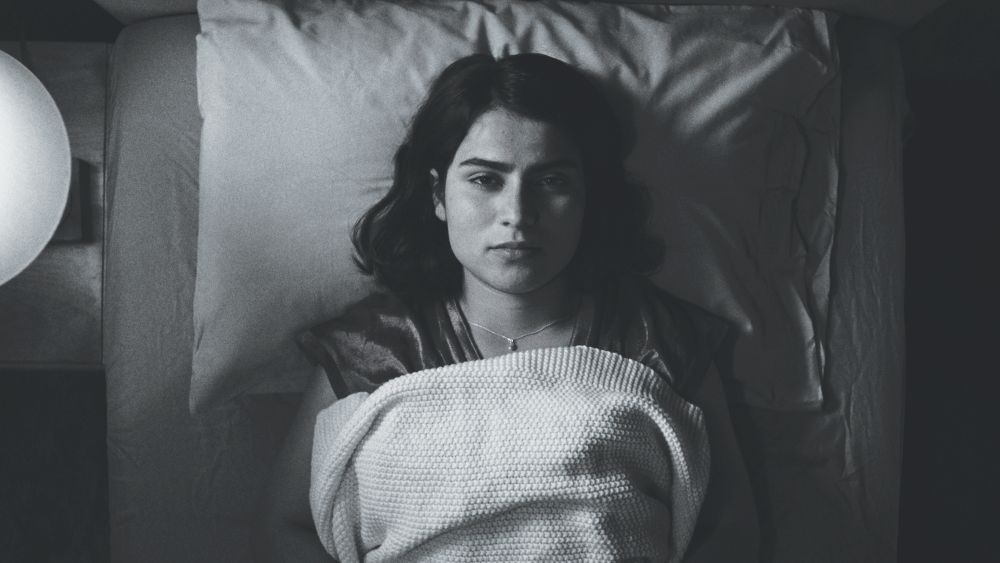

She tells him flatly that her family was threatened because of her job and that she was forced to leave the country. Any emotion that Donya is suppressing is telegraphed across the room as a warning shot. She’s more interested in a prescription for sleeping pills than she is in healing. Her persistent bouts of insomnia have left her in a torpid, dreamless limbo.

In Babak Jalali’s film Fremont, the city features less as an actual place—architecture and landscape shots rarely appear on screen—but as a psychic weigh station where Donya lands to evaluate the state of her soul. Jalali’s camera is as stagnant as his main character. The director repeatedly places Donya at the center of the frame, head-on or in profile. He creates a portrait of a pensive young woman on the verge of figuring out what comes next.

During the day, Donya works at a fortune cookie company, sealing fortunes inside of cookie shells. She wears a hairnet while repeating mindless tasks and chatting amiably with her coworker and her boss. At the end of a work day, Jalali, with a documentarian’s eye, captures Donya’s solitary home life in a nondescript apartment complex. Two of her neighbors are also Afghans. One suffers from insomnia too. When Donya hears him standing outside on their shared front walkway, they talk peaceably and stare up at the stars. The other neighbor refuses to speak with her. He considers her a traitor because of the work she did for the U.S. Army.

Shot in black and white, Fremont conjures up a visual spell that’s similar in tone to Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise (1984). Zada delivers her lines dryly, letting paragraphs of thought remain unsaid. Everything that happened to Donya and her family during the war stays off screen, in the past. The quiet, calm stasis of her current life is the photographic negative of what came before. Color has been drained out of her life.

Even with the few, limited social interactions she has in Fremont, Donya is wary of misunderstandings and condescension. Her eyes express what she’s afraid to articulate—growing feelings of impatience and frustration. In Donya, Jalali and his co-writer Carolina Cavalli have created a character who’s slowly learning to appreciate the absurdity of her situation. To have arrived in that place, she’s exhausted her reserves of self-pity. Donya also doesn’t indulge in melodrama.

As in Jarmusch’s films, small moments in all of the characters’ lives are carefully observed and recorded. Their foibles, like birthmarks or scars, mark them as unique individuals. Donya regularly returns to an Afghan restaurant to eat dinner. The waiter there is a paternal figure who counsels and encourages her. He correctly reads her as a person whose appetite for life has been stunted by her experience of war. And he likes to watch the Afghan soap opera on the restaurant’s wide screen television.

During Dr. Anthony’s first few scenes, he registers as a comic figure. His simplistic questions don’t reach Donya. As Fremont progresses, Jalali and Cavalli provide him with an opportunity to adapt to his patient’s trauma. Dr. Anthony spends one session reading Jack London’s novel White Fang to Donya and finally elicits a meaningful response from her. Knowing that she spends her days at a fortune cookie factory, he writes out several fortunes, cuts them out and shares them with her. Subsequently, Donya writes a fortune of her own and sends it out into the world.

Until the final third of the movie, Fremont is largely plotless. The audience is watching a character in formation, the coming-of-age story of an immigrant in America, a young woman having to start a new life without the support of close friends or family. Donya’s life in Fremont is also devoid of sensual pleasures—her chasteness though is all-encompassing. It’s spiritual, emotional and physical. Her body is so tightly coiled up with tension she’s unable to relax into a single night of restful and restorative sleep. When Donya eventually arrives at a fateful turning point, it’s miles and miles away from Fremont.

FREMONT

3Below Theaters

San Jose

Sept

15-17

multiple showtimes

$15