The history of Angel Island, the second largest island in the San Francisco Bay, dates back thousands of years. It was grounds for hunting and fishing for Native Americans, a trading post for Spanish explorers and a cattle ranch during the Civil War.

Nicknamed the “Ellis Island of the West,” it was also the biggest immigration entry port on the West Coast in the late 19th century.

But unlike Ellis Island, which welcomed predominantly new European arrivals and was a symbol of freedom and hope for a better life, Angel Island detained, interrogated and enforced discriminatory policies on its immigrants, most of whom were Asian.

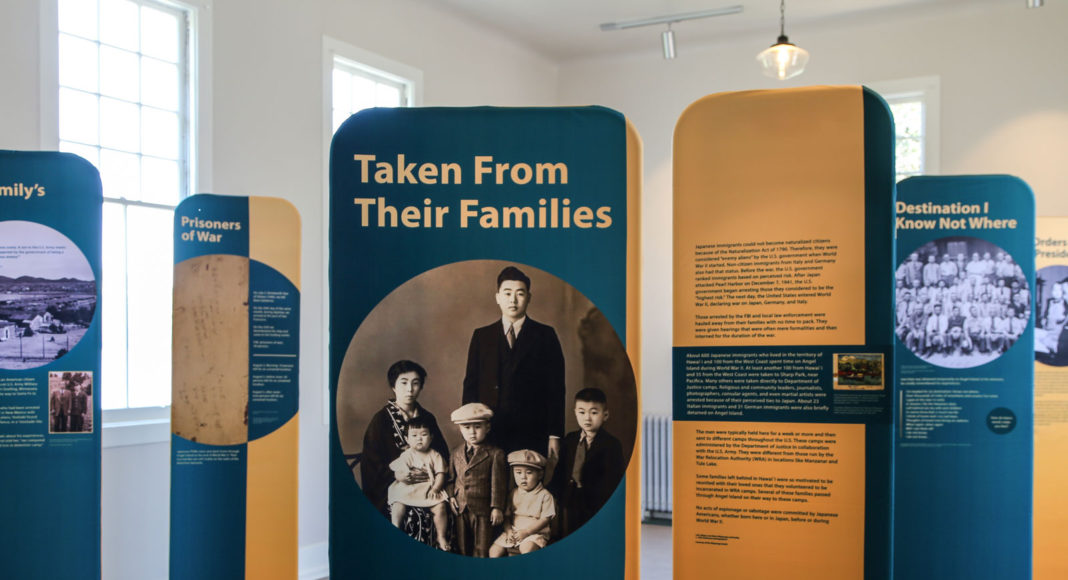

This dark and little-known chapter of Angel Island is the subject of Japanese American Museum of San Jose’s new exhibit, “Taken from their Families: Japanese American Incarceration on Angel Island During World War II,” which runs through June 23. The traveling show explores 24 individual stories from the nearly 700 Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants from Hawaii and the West Coast who were interned on the island.

From 1910 to 1940, Angel Island was used as an immigration detention center, processing approximately a million immigrants from more than 80 countries, primarily China, as well as Japan, Germany and Italy. They were forced into cramped barracks and subjected to invasive health inspections and other cruel conditions, a result of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

To cope with their environment, many of the Chinese immigrants left behind inscriptions, poems and images carved into the barracks’ walls (more than 200 of them have survived). After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, which deemed Japanese Americans enemies and authorized the mass internment of 120,000 civilians of Japanese descent along the West Coast.

The Japanese men incarcerated on Angel Island were husbands and fathers, mostly over the age 40. They were clergymen, gardeners, businessmen and community leaders who were torn from their homes and families. They were detained in the facility only for a few weeks before being transferred to internment camps throughout the country.

“None of these men had ever committed any acts of espionage or sabotage,” exhibit curator Grant Din says. “Many were ministers, Buddhist or Shinto ministers, and few Christian ministers who had helped Japanese immigrants as well. There were photographers who were accused of spying. There were people who did language translation or martial artists who had gone to Japan to enter tournaments. Because of that, they were under suspicion. But generally, they were just regular people for the most part.”

The immigration center functioned until 1946. After years in disrepair, the site was renovated by California State Parks and designated a National Historic Landmark. Founded in 1983, the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation preserves the island’s legacy on its website and through rotating exhibits, tours and programs.

A few years ago, Din, a researcher and volunteer at the foundation, teamed up with Marissa Shoji. Then a Girl Scout and high school student from San Jose, Shoji discovered her own family’s roots on Angel Island and contacted other descendents.

Together, Shoji and Din created the traveling exhibit, which uses banners, maps, photographes, text and interviews to trace each immigrant’s journey—from the date of their removal to their arrival at Angel Island to their relocation to other camps. Their research also looks into the detainees’ lives following the war. Another section of the exhibit features books and poetry written by the survivors about their incarceration.

“We want visitors to learn that these were regular people,” Din says. “They were not working for the Japanese government by any means. They were just arrested on suspicion. They had nothing. Almost all of them were taken away from their families. We’ve always talked about intergenerational trauma, but this is something that people didn’t talk about. They didn’t talk about their experiences. And so the next generation often doesn’t know about this. And so when they learn about it, they’re always either shocked or want to know more.

“I want people to know that they should talk about the past because it’s very healing in some ways,” Din continues. “By learning about what they went through, the second or third generation can understand how amazing these folks were to go through something that especially happened to Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants.”

Taken from their Families: Japanese American Incarceration on Angel Island During World War II. Admission $12. On view Thu-Sun, noon-4pm, through June 23 at the Japanese American Museum of San Jose.