The intersection of Almaden Expressway and Canoas Garden Road is not what it used to be. And it never was.

Getting there in the 21st century was easy. I took the light rail to Curtner and then exited the station into a perpetually empty parking lot. At four in the afternoon, I saw maybe 10 cars on what looked like three acres of desolated concrete. There were signs for “compact parking,” one of which was bent over at a 60-degree angle, as if a truck had backed into it. Along the sidewalk, the parking strip was filled with smashed heaps of wet leaves, in a dead state, until the next wandering leaf-blower dude pushed them further down the sidewalk.

Yes, there were plans to do something with this parking lot—transit-oriented development, as they called it. As with everything else, there were meetings. Committees. Studies. All leading to something that will probably involve overpriced housing, a Chase Bank and a Chick-fil-A.

In fact, this entire area has been a convoluted urban planning disaster for at least 50 years, but, as a travel writer in his own hometown, I did not show up at Canoas Garden Road just to complain. I showed up to contemplate the grand sweep of history as I crisscrossed the parking lot, devoid of all life except for a few squirrels and a taxi driver asleep in his cab.

There was even a “no skateboarding” sign at the edge of the park-and-ride lot. The whole damn lot was empty. What was the point of banning skaters?

One of the best lines in Viet Thanh Nguyen’s novel The Sympathizer goes something like this: “America’s only contribution to architecture is the parking lot.” He was talking about suburban wastelands in Orange County, but he may as well have meant San Jose.

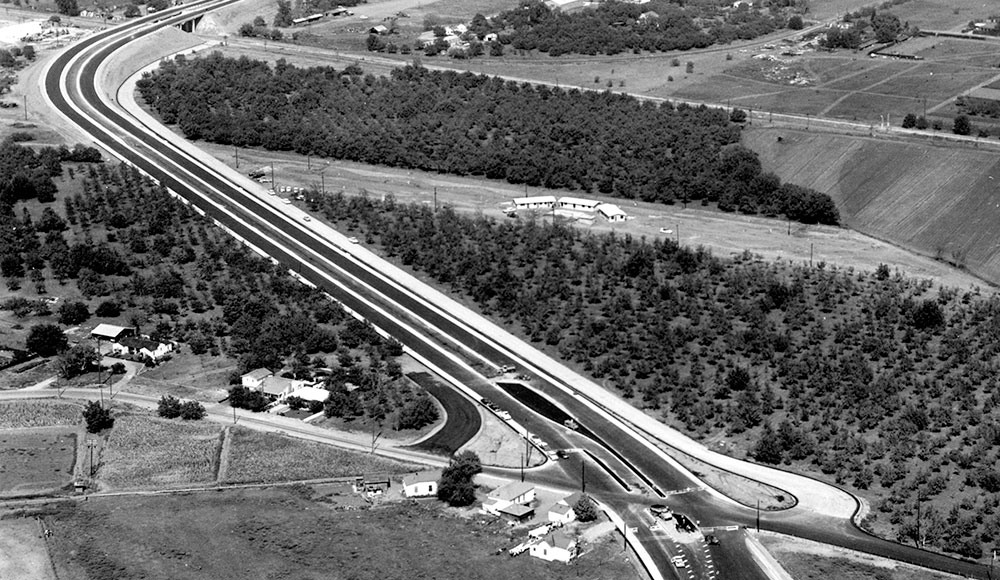

To really grasp the absurdity, one only needed to look at old back-and-white photos. The first section of Almaden Expressway debuted around 1959, only going as far south as Canoas Garden, with a price tag of $800,000. At the time, the Curtner Avenue intersection was almost finished. Orchards and farmland filled the surrounding landscape.

Now, in 2025, navigating these parts on foot made the past come alive even more. The grand sweep of history felt apocalyptic. I imagined the forces of time that first paved over the orchards with expressways and thoroughfares, then installed sprawling mobile home parks and mega churches, after which came a light rail, sound walls and a freeway, and only then to see the park-and-ride lot go straight to seed. All in the span of 60 years.

The Nobel Prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk wrote a masterful memoir about Istanbul, his hometown, a place he never left. He annoyed many locals because he focused on ruins of fallen empires, crumbling derelict neighborhoods and the city’s more melancholic dimensions. In several chapters, he discussed previous travel writers who visited Istanbul in the 19th century, describing neighborhoods which were then green pastoral landscapes, but now, in Pamuk’s time, were transformed into noisy, polluted villages.

Pamuk wrote: “To discover that the place in which we have grown up—the center of our lives, the starting point for everything we have ever done—did not in fact exist a hundred years before our birth is to feel like a ghost looking back on his life, to shudder in the face of time.”

This is exactly how I felt after looking at an old photo of this neighborhood and then wandering down Canoas Garden Road from the light rail station, across Curtner and toward Almaden Expressway, with Highway 87 just to the east. What used to be a vibrant agricultural epicenter was now an ugly soot-colored wasteland with hideous monolithic overpasses, broken business signage on every corner, sidewalk graffiti and traffic bottlenecks in every direction—yet another ruinous landscape designed by generations of city planners that hated pedestrians. The ubiquitous crumpled shopping carts only added to the charm.

The good thing? My Canoas Garden journey rekindled an appreciation for Orhan Pamuk, one of the all-time giants of world literature. His words gave me hope to carry on.

Of course, no one will ever win a Nobel Prize writing about San Jose. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

Great piece, Gary. I enjoyed the analogy of “what could have been” and your reflection as to ” “why it never will be.”

Thanks, Gary!

Good article Gary! We grew up with the city growing up. And sprawl!