In the early 2000s, when Suzanne Guerra began working in San Jose, she found herself in a surprising predicament.

“I was looking for local Mexican-American history—interviews, oral histories, anything else,” the public historian reflects. “I could find practically nothing at all in any of the archives and libraries. And that to me was really very shocking because the community has been [in the region] for such a long time.”

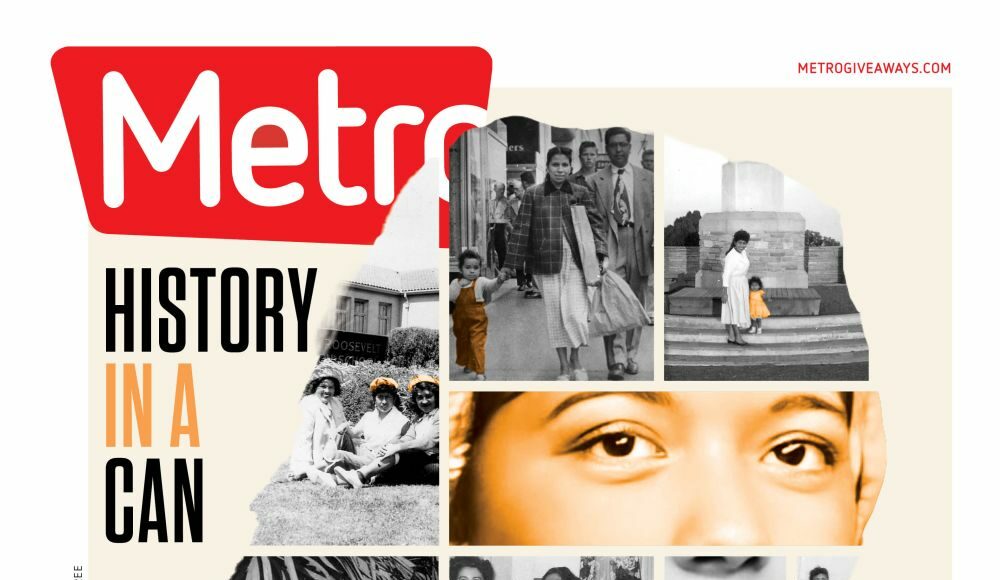

Enter Before Silicon Valley, a research project that Guerra has co-directed for nearly 20 years. Based at SJSU, the project focuses on the lives of Mexican agricultural and cannery workers between 1920 and 1960. Recently, the project hit a significant milestone. With the launching of a brand new website, the yields of two decades of research are now available online for the public’s perusal. The site features mini-documentaries, photographs, a curriculum for K-12 teachers and more than 80 oral histories.

Early October, the organizers ushered in a pair of grand festivities. At Roosevelt Community Center, the 15-piece Bernie Fuentes Band performed a Mexican swing music for a tardeada. There was also a 10-mile guided bike ride visiting several prominent historic sites. For those interested in a self-guided bike tour, the route for the ride is available on the Before Silicon Valley website.

THE VALLEY OF THE HEART’S DELIGHT

For much of the 20th Century, the South Bay area was the world’s largest fruit-producing and processing center. Promoted as the Valley of the Heart’s Delight, the region relied on a labor force of Mexican immigrants who worked migratory seasonal jobs in the orchards and fields. A turning point occurred in WWII, when higher-paying cannery jobs opened up to Mexicans and Mexican-Americans. These year-round posts enabled them to establish a home base and vibrant communities in neighborhoods across Santa Clara County.

“Once they did that, they started building community and cultural organizations,” says Dr. Margo McBane, one of the project’s co-directors. “This led to a more stable population that wanted a political voice, which led into the Chicano movement of the 1960s.”

GETTING STARTED

It was in the 1970s that Dr. McBane began digging into California’s agricultural history. As part of her work with United Farm Workers—then housed at San Jose’s Sacred Heart Church—she interviewed Dorothy Healey and Elizabeth Nicholas, a pair of organizers of the 1930s cannery strikes. These conversations made a lasting impression on her and set the stage for a storied career. She became a public historian, penning a dissertation on citrus workers of Southern California. Around the time of the dotcom boom, McBane took on a post at San Jose State. “It was 2002, and it was so different,” she reflects. “The landscape had changed so much from the 70s.”

Soon, she and her research partner, Suzanne Guerra, landed a contract with History San Jose. Their charge was to research and record the century-long history of Del Monte’s Plant Number 3, located at Auzurais Avenue and San Carlos Street. Once the world’s largest fruit cannery, the plant employed generations of workers between 1893 and 1999.

“Entities do a good job of documenting corporate history,” Guerra notes. By contrast, she bemoans, workers’ stories often remain untold. That’s what makes the work of Before Silicon Valley a vital template. “It’s more than just the history of the founders, the investors, the equipment and the plants themselves,” she says. “What’s more important is the community that enabled it all to happen—the folks who went to work every day and did those jobs that were essential to keeping it going.”

Cannery work was once so widespread that residents with deep roots in our region frequently have ties to the industry. As such, to meet interviewees for the project’s oral history component, McBane didn’t have to go far. Instead, she turned to her students. “I just said, ‘Anybody here got relatives who worked in the canneries? Of course, most of them did.”

Though the old 160-foot-high Del Monte water tower remains as a landmark, much of Plant Number 3 has long been demolished. Still, Guerra reflects that its legacy lives on. She says, “I always tell people that buildings and structures may disappear, neighborhoods may be gone, but people hold on to their memories, and they also have personal artifacts that have stories with them.”

And when it comes to chronicling peoples’ pasts, these researchers go deep. “We believe in oral history, which is full life interviews,” says McBane. “We don’t do stories. We don’t do little snippets. We cover family life, migration, housing, work, cultural backgrounds, community activities, all of that. We want to make sure we document it for future researchers. So when they’re looking at things, they can see context and motivation for why people did what they did.”

EXPANDING ACCESS

“We decided that we needed to do more,” McBane reflects of that project’s close. “So much had been written about Los Angeles’ Mexican agricultural workers, but so little had been written here. And San Jose was as important as Los Angeles. It was the mecca for Mexican agriculture, cannery work, and culture. And then we have the Civil Rights Movement that happened here with Ernesto Galarza and Cesar Chavez.”

In 2011, the pair secured a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Initially, they intended to create a traveling exhibit that would premiere at museums across the United States. Their plans evolved at the urging of their third co-director, Kathryn Blackmer Reyes, a SJSU librarian and the director of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library’s Africana, Asian American, Chicano and Native American Studies Center (AAACNA). Instead of a traveling exhibit, Blackmer Reyes suggested an online one.

Guerra notes that this format is a win for making information more accessible. “It will be bilingual, open 24/7 and available online to anyone who has access anywhere in the world. Anybody anywhere can look at what’s there and begin to have access to things they might not yet be aware of,” she remarks.

THE PALOMAR BALLROOM

In addition to researching local canneries, Guerra scored a contract to study the Palomar Ballroom. Built in 1946, this music venue welcomed audiences for nearly 60 years. As the first racially integrated ballroom in San Jose, it hosted big bands, vocalists, jazz legends as well as early rock and roll performers from the US, Mexico and Cuba. The Mexican-American community gathered there frequently for political and social events.

“That was pivotally important,” says McBane. “Cesar Chavez used [the Palomar Ballroom] as a fundraising place for the Community Service Organization, and it was one of the main ballrooms of the area. So we did this whole history of ballrooms in San Jose, and nothing had been done like that before. We interviewed the Bernie Fuentes Band and De La Grande. And we interviewed people who went to ballrooms.”

Historically significant places often disappear, whether they’re damaged in a disaster or demolished at the hands of developers. While this sad fate is ordinary, it’s less common for the memories of a place to survive. “Even though the building was gone, the stories were preserved,” Guerra is proud to point out. “We did an interpretive exhibit that is displayed on the new building. It recalls the history of the place and the activities that went on there too.”

What’s more, on the Before Silicon Valley website, visitors can watch some of the stories unfold via one of four mini-documentaries. Focusing on cultural spaces like music venues that afforded a sense of belonging, the short film features fliers, photographs and interviews with several elders.

TEAM WORK FOR THE WIN

“It’s been a very team-driven project,” McBane says. “And it’s only as good as the team.” She lauds the students and volunteers who have contributed to the effort, including some who have stuck with it for over a decade. She notes, too, the importance of engaging locals in the work. “I was always trying to get people from the community to document the community,” she explains.

One such volunteer is Carlos Velazquez. “It’s a personal passion of mine to really dig deep and celebrate our Mexican-American and Chicano history here in San José,” says Velazquez, who credits his family ties as investing him in this work.

In 2017, he attended a talk by McBane and Guerra at The East San José Carnegie Library. The pair shared about oral histories they’d been gathering, and Velazquez found himself hooked. “I learned so much at the talk, I immediately let them know I would help out however I could,” he enthuses, noting his marketing and communications background. A year later, McBane and Guerra reached out. In the years since, Velazquez has applied his skills to launching a social media page, crafting language for their site, and community and media engagement. His aim: to make it easy for people to connect with the material.

“It’s a really crucial time,” says Velazquez. “We’ve already lost so many people in the last 10 years. I think it’s helping inspire more families to say, ‘Oh, hey, my parents also worked in the canneries, or my grandparents did.’ A lot of our history is stored away in peoples’ photo albums and family stories. And so it’s projects like this that hopefully will inspire others to really see how important their archives are, not only for their immediate family, but for the city’s and the region’s history too.”

Part of what drew him to Before Silicon Valley was its focus on the early twentieth century. “For many people, San Jose was born in the 50s and 60s, when Silicon Valley formed,” Velazquez reflects. “I spent some time in Chicago, and the city’s earlier history is still visible in people’s lives. The Chicago fire, the mobsters, all the music—it’s such a prominent part of the fabric of the city. It’s so interesting that San Jose, which has a rich history before the 1950s, that history is just … nobody knows it. This history needs to become part of everyone’s history, and it needs to be celebrated and known.”

In addition to established San Jose residents, Velazquez sees newcomers as a key audience for the website’s offerings. “They’re hungry to connect with a city that they just moved to,” he observes, “and they really need to understand the foundation for how this city was formed.”

A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE BARRIO

A fascinating aspect of this work is the light it shed on several key neighborhoods where Mexicans and Mexican-Americans once lived. Velazquez notes that locals tend to be familiar with some iconic historical neighborhoods like Mayfair and Sal Si Puedes, which translates to “get out if you can.” The latter, Velazquez mourns, was mostly torn down during Highway 680’s development, save for a few remaining 100-year-old houses. “Right there around Jackson and Kammerer is where that neighborhood was,” he says. “And it was the oldest area in the East Side for the Mexican community. It doesn’t exist anymore.”

When it comes to downtown, Velazquez cites South First Street as an area of particular significance. “My dad had his first tailor shop on First Street and San Carlos,” he shares. “It was through this project that I really understood that this was a huge district for the Latino community. It was where they came to do business in the 40s and 50s.”

This research is a corrective to a common narrative that miscasts the South First Street area’s history as solely blight-stricken. “From what I’d been told, South First Street was this decrepit place that nobody wanted to go to,” Velazquez shares. “It was full of strip clubs. It wasn’t until the 1980s, when all these underground punk clubs started coming in that it became a cool spot. That’s great. But they never talk about how it was a vibrant business district for the Latino community.”

Another contributor to the project, Videographer Fernando Perez, boasts a special connection to West San Jose. “My grandfather came to San Jose in the early 1960s,” he shares. “I never really met the guy, but I knew stories of him driving a forklift, of him working hard to buy a home in Palm Haven, and just hearing about his connection to the westside of San Jose. That’s where I grew up. This project is my way to connect with parts of my roots, my immigrant experience.”

Perez has had the joy of co-organizing five community events, featuring scholar talks and documentary screenings, across Santa Clara County. Among these was a cannery worker celebration at Gardner Community Center last April. “A lot of people have this East San Jose Pride. I’m not knocking that, but I think the West San Jose community has a very important part in our history,” he states. “Gregorio Mora-Torres, a retired professor at San Jose State, is working on a book highlighting the Mexican colonia that existed right there.” The event was a resounding success, bringing out the loved ones and descendents of cannery workers who lived in San Jose’s West Side. “That really sealed it for me that I wanted to be part of this project,” Perez remarks. “People came out and it was just awesome.”

WHAT’S NEXT

For the researchers who’ve devoted themselves to documenting this history, the end of the project is bittersweet.

“We’re not going to continue this work in the future,” Guerra reflects, “but other people will. We want them to use the resources we have collected as a start and to ask their own questions. That’s what I hope for. They will delve even further, they’ll have new perspectives and angles, because there’s so much still to be learned and documented.”

Fernando Perez echoes Guerra’s sentiment. “I’m looking forward to other projects that come out of this,” he says, noting a resurgence of locals sharing photos and history pieces on social media. “The history’s out there. It’s underneath the streets we drive everyday. I can’t wait for other people to go out and dig into it.”

Wow. I grew up in San Jose, even as an Anglo, spoke good Spanish, knew how to be respectful of the culture, had lots of friends from the East Side, ate at a great restaurant name La Capri at 13th and Hedding where one HAD to speak Spanish to get served, had a Latino girlfriend, used to hang downtown during the 60’s. Sad to think all that history is lost.

What’s missing here is noting the history of the Mexican and Spanish people who lived in and above the town of New Almaden, (West SJ) back in the late 1800’s, early 1900’s. They were so instrumental in developing the cinnabar mines out there. I knew people whose grandparents had moved there long before I came along. Went to Pioneer HS with a lot of them. Because I spoke Spanish, I was accepted more by them than the poor little rich kids of Almaden Valley, tu sabes?

Historic preservationists in Palo Alto are fighting to preserve the same history in the building known most recently as Fry’s Electronics, previously Maximart,

which was the Thomas Foon Chew Bayside Cannery. The Palo Alto location made this the third largest cannery in the U.S. after Del Monte and Libby’s due to the influence of Herbert Hoover who shipped product to European WWI War Relief in Belgium as well as well into WWII to feed American soldiers. Although Palo Alto City Council already voted to approve the developer Sobrato’s plans for 74 luxury townhomes including demolishing 40% of the original building, we

are fighting for Plan A Preserve the entire building to qualify for Interior Dept. historic status and for Plan B Preserve the space under the two monitor roofs to provide a comprehensive historical exhibit covering the role of Chinese railroad workers which created Leland Stanford’s wealth and political career through the many hardships and discrimination such as the Chinese Exclusion Act. Both Thomas Foon Chew and Lew Hing’s Pacific Cannery in Oakland did much to show the huge contributions made to the early California West, against all odds.

I grew up in SJ when it was transitioning from an ag town to “Silicon Valley”. The people were nicer when SJ was a “cow town”. The major knock against SV is that it has fostered a sense of impermanence throughout the community. Today I live in a community (Monterey) where the past is revered, respected and preserved. There’s a great sense of community here. In SV the past is seen as an impediment to the future and must be destroyed at every opportunity. It’s why SJ lacks soul and a sense of place

Great article, but what’s the website of the project?

Excellent work Carlos you have completed a work that is far more challenging then most people would assume.The thousands of hours of research of conversations ,thinking,meditating..I thank you as a member of the community your research covered.You have brought a renewed pride,dignity,legitimacy to Chicanos and Mexicanos in San Jo.

The Horseshoe specifically and west side in general has not been given the proper due within the Context of Chicano Movement ,Lowrider Movement History.Your work has made significant contributions to the Body of knowledge that exist giving the Mexican Experience a more visible role in the evolution of San Jose Culture,economy,politics.

Gracias a todo y todo mi sinceramente

Paul Soto VHS

I believe that’s my mother’s face on the cover. We lived in San Jose when I was little, in the 7trees neighborhood. We were close to the drive in and would walk in with folding chairs though and opening from the street. I know we have cousins in San Jose, but I have lost connection.

Thank you for the history