A champion of nonsense and irrationality arrived in Palo Alto last week at the Pace Gallery. Adam Pendleton’s solo show in California, “Which We Can,” is just one of many stops on the Brooklyn-based artist’s move toward cultural ubiquity.

Pendleton’s work has recently been displayed in Detroit, Minneapolis, Baltimore, Berlin, New York and, not least of all, the 2015 Venice Biennale. Vogue and the New York Times have featured interviews with him this year. At the age of 33, Pendleton has gazed at the zeitgeist, and now it’s gazing back at him.

We’re living through an era that’s resistant to the idea of definitive meanings. Headlines are now filed on a daily basis with accusations, recusals, apologies and denials. Truth suffers from dubious slippages as it moves from the left to the right and back again. In a coded response, here comes Pendleton, boldly forsaking color and easily decipherable canvases. In some of the literature printed about him, there are references to his influences, including Ad Reinhardt.

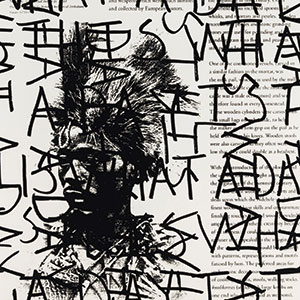

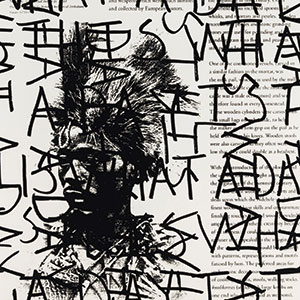

But when Reinhardt’s abstractions went black, the temperature in the gallery cooled down. The point of view is from absolute darknessthe bottom of the sea or somewhere out in distant space. That’s not the case with Pendleton’s series of 30 silkscreens, Our Ideas. Mounted on the wall in a grid formation (10 images across by three down), these messy squiggling inks provoke and agitate. They share more DNA with Franz Kline’s angry language of unidentifiable shapes, his mangled hieroglyphic paintings from the 1950s.

If you walk into the gallery unfamiliar with what you’re about to see, the scrawls and masks, the distorted faces and inverted words, they’ll all resist your best and most logical interpretations. The artist’s own treatise on his workwhat he tells us we’re looking atis crucial to be able to read meaning into it, if being told what to look for appeals to you. Collectively, the walls shimmer with rage and disorder, although those chaotic thoughts and emotions are carefully contained in glass-fronted, framed rectangles. Pendleton has also written, with other contributors, a book-length manifesto on his practice entitled Black Dada Reader.

In an interview with Pin-Up Magazine, Pendleton says he discovered the term in the Amiri Baraka poem “Black Dada Nihilismus.” The artist explained that “Black Dada is a way for me to talk about the future of the past.” Without risking further obfuscation, his statement in the April New York Times feature is a clearer statement of purpose: “[Black Dada is] a way of articulating a broad conceptualization of blackness.” More helpful still is Behind the Biennale: Adam Pendleton Brings “Black Lives Matter” to Venice, a short video posted online by Artsy.

Pendleton stands in his studio and explains the idea behind his contribution to the Biennale. He says, “Some things end up really signifying the moment they came into being.” The moment he was addressing in 2015 was the one in which Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown were fatally shot. The camera hovers over some of the work in which the artist has incorporated language from the Black Lives Matter movement. One of the larger works at Pace, Untitled (A Victim of American Democracy), also employs this strategy.

Pendleton takes the title from a 1964 speech “The Ballot or the Bullet” by Malcolm X. It’s also part of a series of paintings that could have been one enormous wall of graffiti that’s been cut apart and separated. They’re silkscreens that have also been spray painted, again, only in black and white. You can make out letters but they’re cut off or solitary. Faces appear from spreading blots that seem like Rorschach tests. Do you see anguish and terror, or the blankness and dread of nothing at all? If as Pendleton suggests in the Artsy video that his work reflects our particular political moment, it’s no wonder that he’s in such high demand at galleries around the world.

Adam Pendleton: ‘Which We Can’

Thru Dec 22, Free

Pace Gallery, Palo Alto

pacegallery.com