![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

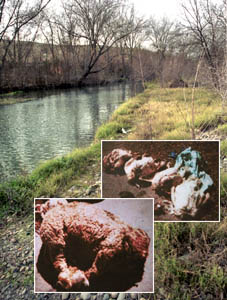

Background photo: George Sakkestad

Public Offering

Four times this past year, Hellyer Park rangers have found the headless carcasses of goats, sheep and chickens stashed by a stream. And some fear that it's part of a religious ritual which--except for the dumping--may be perfectly legal.

By Will Harper

THE SMELL COMING FROM THE THREE large, blue plastic bags was nauseating to Hellyer Park county ranger Julie Heffner. The hot mid-August sun beating down on the Coyote Creek bike trail near Metcalf Road was causing whatever was inside the bags to ripen--quickly.

Something told Heffner that the bags contained more than shredded office documents--and it wasn't just the dizzying stink.

The gruesome scene was eerily familiar to Heffner. Seven months earlier, in mid-January, she wrote up a report after a park maintenance crew came across three bags containing a headless female and male goat and up to eight decapitated chickens.

At the time, Heffner didn't think her finding important enough to call in sheriff's deputies. She wrote a paragraph-long report, treating the January discovery as an illegal dumping.

Looking at the blue bags, they reminded Heffner of the ones she found at the beginning of the year. Those bags had been dumped in practically the same place.

This part of the trail isn't exactly an idyllic urban getaway: It's nestled between the Pacific Gas & Electric substation and Monterey Highway, easily accessible by car. On the other side of the barbed wire fence sectioning off the trail, cars occasionally drive down Coyote Creek Road, directly adjacent to the bikers' path.

Under cover of night, someone could easily drive by and discard the bags without being noticed.

Braving the fumes, Heffner approached the sacks and opened them.

One bag contained the headless remains of a male goat. Another held the headless body of a ram. The last sack was filled with the headless bodies of a dozen chickens.

The bodies could have been rotting here in the sun for quite some time because this stretch of the trail hadn't been patrolled for two days.

This time, Heffner decided to call in a deputy from the sheriff's rural crimes unit to investigate what appeared to be more than an illegal dumping. This looked like a case of animal cruelty.

After all, if it were the castoff of someone who had been poaching for food, the bodies would have been gone, not the heads.

Deputy Joe Fortino had been working in rural crimes for only eight months. He generally dealt with things like cattle rustling. During his brief tenure, he had never come across anything like what he saw along the Coyote Creek bike trail that day.

Fortino also noticed that the legs of the animals were bound, something probably done to keep them still while the killer or killers beheaded them.

Other than having had their heads removed, the bodies of all the animals and birds appeared intact and unmolested to Fortino.

He could only find one clue to pursue: A livestock identification tag on the ram. That meant there should be a paper trail showing who had bought and sold the sheep.

Otherwise, investigators didn't know exactly what to make of their strange finding.

Sure, they had heard of animal mutilation cases in the area. In fact, a string of cat mutilations in south San Jose earlier in the year had pet owners worrying about a neighborhood sicko going around gutting their cats. But San Jose police ultimately concluded that coyotes, not humans, killed the felines.

But this latest finding was clearly the work of humans who probably disposed of these headless carcasses after sundown.

Human involvement raised questions like: What was the motive? Why did the perpetrators not dispose of the heads along with the bodies?

Fortino thought that whoever did this didn't have a conventional motive. He suspected the animals had been used in some kind of ritual or religious sacrifice. That posed a complication from a legal standpoint: The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld the practice of animal sacrifice in religious rituals.

For all Fortino and the rangers knew, the only crime committed was an illegal dumping on county property.

Animal Control disposed of the bodies. Fortino didn't bother to order a necropsy, an animal autopsy. In fact, he didn't even bother to file a report in the months following the August incident.

SINCE THAT TIME in August, Hellyer Park rangers have found headless animal remains on two more occasions in the same area on the Coyote Creek bike trail.

On Oct. 10, a ranger reported discovering a blue plastic bag containing a black goat and "3 to 5" chickens.

Nearly a month later, on Nov. 5, parks officials found six large blue bags containing approximately 50 chickens and doves.

Sgt. John Hirokawa, a spokesman for the Sheriff's Department, the agency leading the investigation, says the ID tag on the ram found in August has been the most significant clue.

According to Hirokawa, Deputy Fortino traced the sheep to a slaughterhouse in Santa Clara County (which he wouldn't name). When Fortino contacted the slaughterhouse operators, they said they didn't know what happened to the ram in question. Although the slaughterhouse keeps records for animals they butcher, the proprietors told Fortino they don't keep records for livestock they sell on an individual basis.

Hirokawa says it's not uncommon for people in rural areas to buy livestock and bring it home to slaughter and eat.

Fortino also went to the animal shelter--where the remains were sent for disposal--to take a look at the dozens of headless chickens and pigeons found in November. But the rural crime deputy found nothing of evidentiary value and thus didn't write a report, Hirokawa says.

In spite of--or, perhaps, because of--the puzzling nature of the case, county officials did not pursue it seriously.

A spokesperson for the county Parks Department acknowledges that rangers probably didn't notify sheriff's investigators when they found more headless animal bodies in October.

As for the sheriff's office, Deputy Fortino didn't bother to file his written police report until three months after the August dumpings. Hirokawa concedes it's standard inside the department to turn in a report within a week of an incident. "We didn't feel he [Fortino] turned it in [in] a timely manner," Hirokawa acknowledges.

And even though investigators consider ritual sacrifice a likely motive in the animal decapitations, they didn't contact experts in the occult or Humane Society officers familiar with the practice until Metro began making calls for this story last month.

FORTY-SEVEN-YEAR-OLD Valerie Voigt boasts having been a practicing pagan or Wiccan for nearly half of her life. Though her rituals don't involve animal sacrifice, Voigt, as a student of the occult, knows the meaning behind them.

Law enforcement agencies, the Palo Alto resident says, have occasionally consulted her on cases where they believe satanism or other cult practices might be involved. The Santa Clara County Sheriff's Department did not contact her on the ongoing Hellyer Park case.

Based on a description of the incidents provided to her, Voigt theorizes the perpetrator could be a self-styled practitioner of black magic. One reason she offers is that, by her calculations, the bodies were dumped around full moons. She adds that black goats, like the one found near the bike trail, are traditionally used in Western black magic.

"One reason this concerns me," Voigt says, "[is that] a lot of people who mutilate and abuse animals later go on to do the same things to people."

Another possibility, Voigt says, is that the perpetrators were practitioners of Santeria, the Afro-Cuban religion where followers sacrifice animals as an offering when asking saints for divine intervention for things like good health or financial well-being. Animal sacrifices are also done during the initiations of new priests. After most sacrifices in Santeria, she explains, the remains are eaten unless the animal was used for a healing ceremony--investigators say the carcasses found near Coyote Creek Road didn't appear to have been plundered for meat.

Goats, sheep, chickens and doves have all been associated with both satanic and Santeria rituals in the past, according to Humane Society officials.

Lori Feazell, director of field services for the Peninsula Humane Society, says the Hellyer Park incidents don't sound like the work of an occult dabbler or pranksters because the perpetrators have returned to the same spot several times to dump the bodies. She suspects a Santeria connection and points out that the underground practice is surprisingly common in the Bay Area. She acknowledges it's almost impossible to quantify the number of Santeria practitioners.

Santeria is and always has been a faith surrounded by secrecy. Its roots go back to the days African slaves from Yoruba were brought to Cuba and forced to accept Catholicism. The slaves continued to practice their native traditions, but kept them hidden from the slave masters by disguising their beliefs with Christian elements, developing a kind of pidgin religion.

As proof of Santeria's prevalence here, Feazell points to the number of botanicas--small stores that often sell Santeria accessories like votive candles, magic dust, oils, pots--in the Bay Area. The San Jose White Pages alone lists four botanicas.

"That tells me," reasons Feazell, who once briefly went undercover in San Francisco to infiltrate the city's Santeria subculture, "that people are going in and out of those shops and keeping them in business."

Botanica Ta Juan on South First Street, which isn't listed in the phone book, is filled with Santeria-related goods like candles, oils and healing herbs. The store's paint-chipped sign advertises "consultados espirituales," or spiritual readings, but the owner refused to discuss anything about his business or Santeria. "I can't help you," he snapped in Spanish.

Not all botanicas sell just Santeria-related goods. Botanica Santa Josefina on Willow Street also sells statues of Buddha as well as household items like facial cream.

NECROPSIES of the remains could provide more clues, say Feazell and other Humane Society officials. A necropsy could verify the cause of death and reveal any sexual or ritual abuse. It could also pinpoint the time of death. Right now, local investigators only have a general idea when the dead animal bodies were dumped and discarded.

Knowing the time of death could show if the sacrifices were performed on special occult days like the full moon or solstice. Unfortunately, sheriff's investigators here never ordered a necropsy of any of the mutilated livestock found in Hellyer Park.

"When there's an obvious cause of death," explains Sgt. John Hirokawa, "we don't usually ask for a necropsy. In these cases, there was no question as to the cause of death."

While necropsies could have provided a few clues, Bay Area humane officers point out that they are not nearly as valuable as having a witness who, say, gets the license plate of the person seen dumping the bodies.

"It's a difficult case to solve [without witnesses]," Feazell says, adding, "That's why I went undercover [in San Francisco]."

Further complicating things: Constitutional protections to freedom of religion. In 1993, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down an ordinance in the Miami suburb of Hialeah--which has a significant number of Santeria followers--banning animal sacrifices in religious rituals.

Eric Sakach, the western regional director of the Humane Society of the United States, contends that despite the High Court ruling, ritual sacrifices must still comply with state and federal humane laws designed to minimize suffering.

Santeria followers have argued that their methods are more humane than those used by the beef and poultry industries. One Santeria website proclaims, "When an animal is sacrificed ... it is first and foremost done with respect--respect for the orisha being offered this life and respect for the little bird whose life is taken in order that we may live better."

Sakach concedes that ritual sacrifices can indeed be done humanely. But he quickly adds, "There's nothing to safeguard that these animals are being killed humanely in these rituals [because they're done in secret]. There's no oversight."

Sakach says he has seen a rare videotaped Santeria sacrifice ceremony in which the priest uses a dull knife to saw off, not chop off, the heads of several chickens and a goat. He considered the method inhumane because it took so long to kill the animals.

This week the Sheriff's Department assigned more detectives to the case, according to spokesman John Hirokawa. He also says that if more bodies are found in the future, investigators will consider ordering necropsies.

"It's disconcerting to us that they're being dumped on county land," Hirokawa says. "We have to do something."

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

Head Trips: Bags of headless animals have been found in this location near the Coyote Creek bike trail, which runs close to Metcalf Road. Investigators believe they were dumped there at night.

Head Trips: Bags of headless animals have been found in this location near the Coyote Creek bike trail, which runs close to Metcalf Road. Investigators believe they were dumped there at night.

From the January 4-10, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.