Contrary to popular belief, not all artists have the luxury of hiding out in their studios waiting for the muse to strike. They’re working stiffs, holding down a day job, just like the rest of us. Every artist has probably at some point been employed as a domestic or assistant or server.

“Day Jobs” at the Cantor Arts Center, which runs March 6 to July 21, hopes to shatter the image of the tortured, penniless artist cut off from the world. The exhibit explores artists’ day jobs not just as secondary pursuits, but as sources of inspiration.

Veronica Roberts took six years to curate the original show, which opened last year at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, TX. But she spent more like 20 years speaking with artists, curators and colleagues about how their nine-to-fives influenced their creativity.

“There’s this impression that artists work in isolation,” says Roberts. “Jackson Pollock, Frida Kahlo, Picasso. As someone who’s worked with artists for 20 years, that is the opposite of my experience. So many artists are working incredibly hard and are in workplaces with other people. Creativity isn’t necessarily coming from isolation, but is connected to their own lived experiences, even mundane moments of their lives. It can come from so many different places and hopefully will allow us to look at artists not as isolated figures, but as key, integral members of society. I think that we put artists on a pedestal and that’s not been productive. They’re not this rarefied species. They have their own challenges and realities. I think we’ve overdramatized what it means to be a creative person.”

The works, which date back to the 1950s, are organized into “Art World,” “Service Industry,” “Media and Advertising,” “Fashion and Design,” “Caregivers” and “Finance, Technology, and Law” categories. The artists range from new or emerging ones to established big names.

Andy Warhol was a commercial illustrator. Barbara Kruger was a graphic designer for Conde Nast. Sol LeWitt was a receptionist at New York’s MoMA. Jeff Koons was a Wall Street commodities broker.

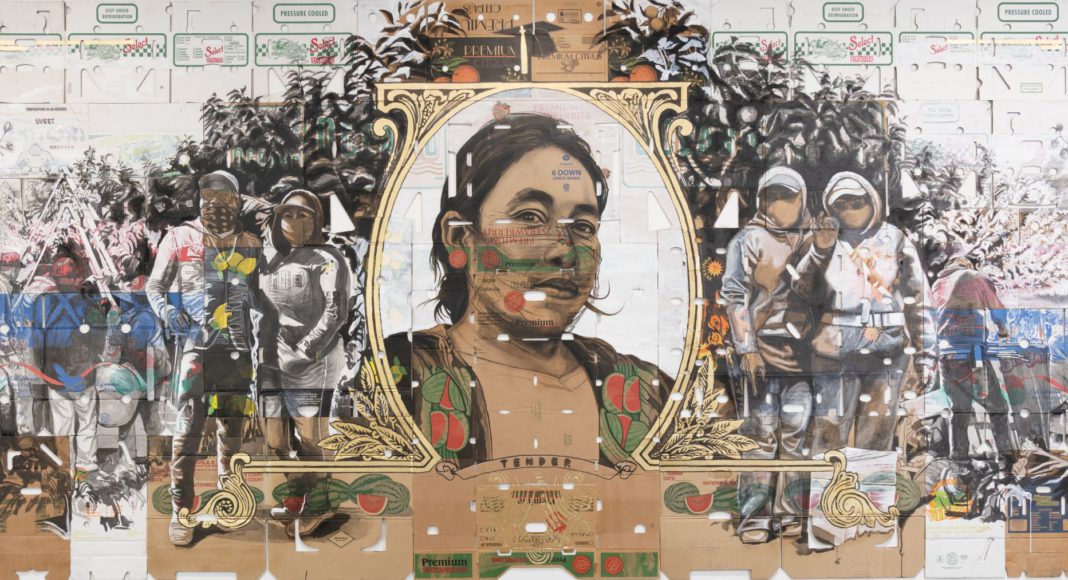

Jay Lynn Gomez, one of six California artists represented here, worked as a Beverly Hills nanny. Her work on paper “Benjamin and Adela in the Jeff Koons exhibition” (2014) shows a custodian and gallery attendant standing in front of Koons’ famous balloon sculpture. Narsiso Martinez worked on farms in Washington state to help fund his arts education. His “Legal Tender” (2022) features undocumented farm workers on a dollar bill painted on a produce cardboard mural.

“He depicts the workers in a role he himself had played in,” says Roberts about Martinez. “He honors their labor and makes us think about how invisible sometimes that work is or how unrecognized it is and all the conversations that we have around produce and the food that we eat on a daily basis. We literally wouldn’t have that if it weren’t for Central-American and Mexican-American immigrants who are making that fruit and that bounty we have in this country, especially in California. He is monumentalizing and honoring that work and it wouldn’t have happened without his own, real connection to that.”

Mark Bradford’s “20 minutes from any bus top” (2002), a collage made with endpapers used to color hair, is a tribute to the years he spent as a hairdresser at his mother’s LA salon. And Chuck Ramirez’s print of a six-foot-tall “Whatacup” (2002/2014) is a nod to Whataburger’s iconic white-and-orange container. The center of the cup reads: “When I am empty, please dispose of me properly.” Ramirez, who worked as a graphic designer for the Texas supermarket chain H-E-B, died in a cycling accident in 2010.

It’s hard to imagine the food industry without creative people. “Dream America” (2015) by Venezuelan-born Violette Bule, once a waitress herself, is a two-panel photograph of a server carrying a load of dishes on her shoulders in one panel, and the American Flag in the other, while her sculpture “Homage to Johnny” (also 2015) is comprised of a metal door, forks and magnets.

“Those were clearly about immigrant labor and the weight of immigrants,” says Roberts.

Roberts also wants the exhibit to dispel the myth that ordinary work is a sign of an artist’s failure.

“If you’re a creative person who has a day job, it doesn’t make you less serious as an artist,” says Roberts. “Artists have been dealing with those challenges of juggling a day-to-day job and making extraordinary work for a long time, and both are possible. They really see that inspiration can come from all these different places. Day jobs can really be beneficial, but it’s exhausting. I hope this show encourages people to figure out how we can better support the artists and creatives in our lives.“

Now Showing, Free

Cantor Arts Center, Stanford