Monday this week, April 7, 2025, marked the 50th anniversary of a landmark piece of occupational safety law, Cal-OSHA’s ban on the use of the short-handled hoe in agricultural work. The order followed a California Supreme Court ruling that declared it an “unsafe hand tool,” a more formal description of el brazo del diablo, “the devil’s arm,” which left farm workers with herniated discs and sciatica amongst related back and skeletal injuries.

Except for a March 29 Instagram post by Monterey County Supervisor Luis Alejo, the half-century of enlightened ergonomic law would have passed unnoticed. The California decision was one of César Chávez’s proudest accomplishments. He was photographed carrying El Cortito as a political prop.

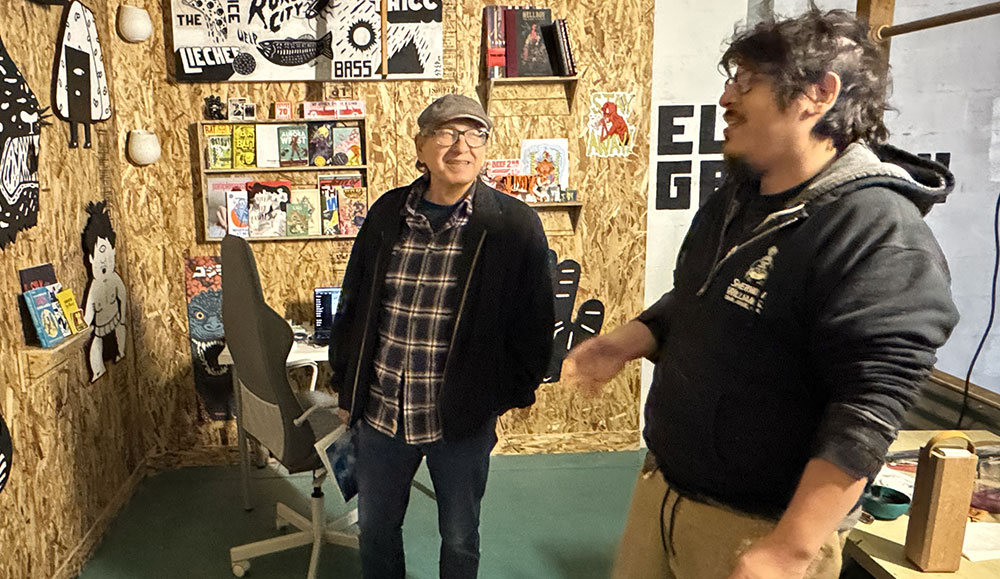

San Jose artist Carlos Pérez used the short-handled tool to weed potato, peanut and sugar beets fields near Stockton, where he moved with his mother and brother from Mexico City in the early 1960s. “When my mom passed away, I found it in the house,” he says.

He keeps it in his Japantown studio as a reminder. “One of the things I remember, especially when I was doing sugar beets, is that I would lay down on the ditches on the road because my back was killing me. I was only 12 years old. This is hard soil. Every strike you make is a strike on your wrist and your elbow, and it goes up to your back. Especially the older men. They began to complain.”

“We’d jump on a bus at the Charter Way liquor store. We didn’t know where we were going to go or how much we were getting paid. ‘You’re going to get $2 an hour,’ they’d say. That was great. We didn’t have to get paid by the bucket to pick tomatoes.”

Two years ago, in April 2023, the San Jose City Council unanimously endorsed a proposal by councilmembers Domingo Candelas, Peter Ortiz and David Cohen to honor César Chávez with a commemorative public art piece in downtown San Jose’s Plaza de César Chávez.

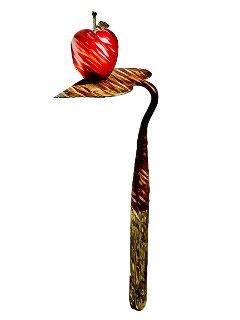

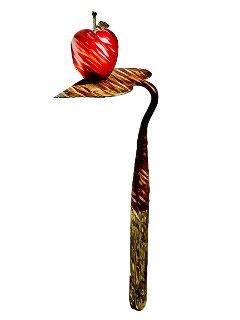

As with many civic resolutions, good intentions often sit on a shelf, like the hoe in the labor leader’s office, preserved at the César E. Chávez National Monument in Keene, California. Perez would like to see Chávez honored by erecting an oversized version of El Cortito at Plaza de César Chávez.

A dramatic public art piece along the lines of San Francisco’s Cupid’s Span would, of course, be more iconic than another bronze bust. Perez’s rendering proposes an oversized reproduction of El Cortito with an apple balanced atop.

The fruit atop of the tool represents the birth of Silicon Valley on the region’s agricultural legacy. “This was a farming community at one time. California is the fifth largest economy in the world because of that…not just high tech, because of the products we prepare from the earth. Everybody eats.”

He knows both industries well. Perez spent years doing design work for IBM in Almaden Valley. His first job was with the Silicon Valley marketing company, Regis McKenna Inc., whose clients included the small personal computing startup Apple.

One of his early assignments was manually drafting the outlines of the Apple logo that became one of the world’s most recognizable symbols and the graphic representation of one of the world’s most valuable companies.

His early renderings of the proposed public sculpture display the apple atop the flat end of the hoe, and Perez plans to evolve the concept after receiving community feedback. “There’s still work to be done. We’re trying to get this germ of an idea out there so maybe it can become a reality.”

“An agricultural community was transformed into Silicon Valley, and that changed the world,” Pérez said. “I want to honor César Chávez and the workers here who laid the foundation for the greatest wealth creation event in the history of humanity.

“We must recognize their contributions.”