home | north bay bohemian index | sonoma, napa, marin county restaurants | preview

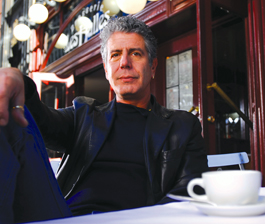

GALLOPING GOURMET: Bourdain appears Jan. 13 at the Wells Fargo Center.

Snouts 'n' Jowls

Travelin' man Anthony Bourdain dishes the good stuff

By Will Coviello

It's been years since Anthony Bourdain worked a long shift over a stove at Manhattan's Les Halles brasserie, which still refers to him as its "chef-at-large." He recently returned from three weeks in Vietnam and Manchuria, filming episodes of his Travel Channel show Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations. In February, he'll set out for Paris, Rome, Beirut, southern India and Liberia. In January, he's on a speaking tour, including his Santa Rosa stopover Jan. 13, doing what comes effortlessly to him: spilling stories about food, cooking, travel and whatever audiences ask him about.

"I'm talking shit," he says laughing. "I stand up there and wing it. Then I get in the van like a rock band and head for the next city."

He downplays his dedicated work habits, but he's certainly found the perfect niche as a celebrity chef since making his name as the cooking world's bad boy, free to say whatever he pleased.

"I got famous by not giving a shit," he says. "In every subsequent project, no one has given me money thinking I'd be [Food Network chef] Bobby Flay. I don't need to be nice or diplomatic. People have really low expectations."

His signature smug candor has been tempered a bit by fame. As he's become more of a celebrity, he's not gone out of his way to dish on others in the profession. He once referred to Emeril Lagasse as a "fuzzy Ewok," but has since befriended him and featured Lagasse's restaurant on his show. And he has said he's glad he'll never have to share an elevator with Marin County's Tyler Florence, star of former Food Network shows like How to Boil Water, who lent his talents to Applebee's menus and ads.

At heart, he's a purist who appreciates chefs, unsung line cooks, food with integrity and the challenges of working in kitchens, but also what foodie TV has done for them.

"On balance, it's good when people talk about food. It's been good for business," he says. "And it means chefs in the heartland can sneak snouts and jowls—the good stuff—onto their menus."

That said, Bourdain remains discriminating. He is a fan of British chef Gordon Ramsay, but not of his show Hell's Kitchen ("The level of competition is so obviously pathetic. People want to know if Jumbo is going to topple over before he cooks anything"). And he likes Bravo's Top Chef, on which he appears frequently ("There are very talented chefs competing," he says, adding, "You are judged on the merits of the food").

Unlike many critics, Bourdain earned his opinions the hard way, working his way up the culinary ladder to Les Halles in the 1990s.

"I was 44, still broke with no chance of ever having a normal life," he says. "I never paid my rent on time. I had no health insurance. I had kicked drugs, and life had yet to reward me for that."

But hard work paid off. In 1999, he finished an insider's look at working in professional kitchens that he hoped to publish in the New York Press, the free weekly, for a fee of roughly $100. After it was bumped from several issues, he took it back and sent it to The New Yorker, which published it as "Hell's Kitchen." Bourdain soon had a book deal for Kitchen Confidential.

He reveled in talking about the ways kitchens actually worked, spilling the unvarnished truth about how long "fresh fish" typically spent in walk-in refrigerators, how restaurants cut corners, and the gritty and indulgent lifestyles of chefs and cooks. That world seduced Bourdain when he took his first restaurant job as a dishwasher in a seafood joint at the age of 17.

"I learned everything I ever needed to as a dishwasher," he says. "Show up on time and do the best job you can."

Anthony Bourdain appears at the Wells Fargo Center on Wednesday, Jan. 13, at 8pm. 50 Mark West Springs Road, Santa Rosa. $35–$49. 707.546.3600.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|