home | north bay bohemian index | music & nightlife | band review

FLIP THE RECORD, WILL YA?: Ben Ratliff's book kindly lets others do the talking.

Between the Lions

Two books on how we philosophize with music

By Gabe Meline

I really wanted to like Joshua Clover's new book, 1989: Bob Dylan Didn't Have This to Sing About (UC Press; $21.95). I hoped it would take an in-depth look at the musical climate of 1989 by assessing a range of pop singles and underground movements and how they refracted world events. I hoped it would, in the words of the inside flap, "boldly reimagine how we understand both pop music and its social context in a vibrant exploration of a year famously described as 'the end of history.'"

Instead, 1989 can be summed up in a few sentences. "Right Here, Right Now" is a Jesus Jones song that's about some stuff. N.W.A. were more popular than Public Enemy. Rave was cool, Nirvana were cooler. The Berlin Wall and Tiananmen Square sometimes but not always influenced pop music. The end.

Never mind that "Right Here, Right Now," reappearing incessantly as a philosophical talisman of Clover's book, wasn't actually released in 1989. Many of the book's subjects—U2's Achtung Baby, pop singles like "Nothing Compares 2 U," "Groove Is in the Heart" and "Freedom '90"—are from a year or two afterward; even the cover photo of Kurt Cobain is from 1990.

"The current of the mainstream is slower to divert than Alpheus and Peneus," Clover explains, and in referencing the Labors of Hercules, along with Joyce, Francis Fukuyama, Guy Debord and Fredric Jameson, we are made to recognize that Clover is well-read in literature and deep thinkers. I wish he wasn't, and I wish he would write readable sentences about music and politics instead of "this congealing of historical process into a pseudo-concrete thing in turn allows antagonism as an entirety then to be subjected to 'the absolute deconstruction.'"

When Clover is making sense, his music acumen remains sound, particularly with a passage on Roxette's "Listen to Your Heart," which happened to be the No. 1 song in America when the Berlin Wall came down. Yet at no point in 1989 are any interviews conducted. All quotes come from preexisting sources. Reading it has the distinct feel of a guy looking up stuff on the internet and commenting at great, monotonous length.

This betrayal, of a potentially wonderful project derailed by gobbledygook, exacerbates the book's tiny motes into giant beams. In contrast to the world-shifting music and events it purports to document, it simply is, pinned under the stupefying weight of its own intellectualism.

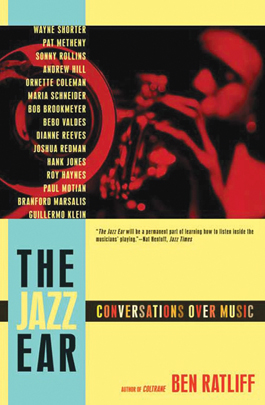

Such problems don't plague The Jazz Ear (Times Books; $15), by New York Times jazz critic and Coltrane biographer Ben Ratliff. In 15 interviews with both giants and lesser-knowns, Ratliff engages in the great tradition of sitting down with musicians in their own homes, throwing on other peoples' music and chatting about it. Kindly, he allows the subjects of his book to do the philosophizing.

Ratliff's request of each musician is to pick five pieces of music that inspire, and the ensuing discussion is never less than gripping. Thus, we get Sonny Rollins in his apartment listening to and effusing about the nuances of Coleman Hawkins' "The Man I Love." We get Joshua Redman, continuing the lineage, sitting in front of the stereo and dissecting Rollins' famous solo from "St. Thomas."

Deep thoughts abound. "Do you think 'the brain' is a good title for the brain?" asks Ornette Coleman, seemingly out of the blue. Wayne Shorter ruminates as Ralph Vaughan Williams' Symphony no. 6 plays: "It's no great mystery about why things are the way they are," he says. "Doubt, denial, fear, trepidation reinforce the artificial barriers to the real, the barriers that keep us from going into the real adventure of eternity."

Ratliff throughout provides background for each musician, so even those who haven't heard of Maria Schneider will have a run-down of her noteworthy accomplishments to date. But the author encourages much more in his listening sessions, capitalizing on the power of music to open people up to thought, emotion, and memory. By the end of Schneider's chapter, after listening to the Fifth Dimension's "Up, Up and Away," she tells a story of a night watchman who teaches a group of injured crows to say "go to hell."

Bebo Valdes talking about crying to Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto no. 2. Roy Haynes' onomatopoetic enthusiasm over Sarah Vaughn's "Lover Man." Branford Marsalis listening to Louis Armstrong sing "Up a Lazy River" and remarking on Americans' inability to truly hear music. Such gems are scattered all throughout The Jazz Ear. Here's to a second volume, hopefully soon.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|