home | north bay bohemian index | features | north bay | feature story

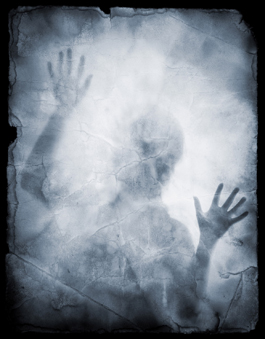

Within Without You: The concept of 'personal space' is vividly acknowledged by the brain.

Out of Body

Body mapping by the brain extends the physical self

By Gabe Meline

F or the past eight years, I've worn one of those over-the-shoulder messenger bags almost everywhere I go. When I first put it on, I felt strangely more in command; on the occasions when I lose it, it's as if a part of myself is missing, and I feel panicked.

I used to think that my attachment to the messenger bag was purely functional, like needing to be in possession of a set of keys—or at its worst, a childish security-blanket impulse. But as the years accumulate and the bag remains on my back, my brain increasingly treats it as an actual extension of my body. I've grown so accustomed to its presence that, even when I'm not wearing it, I compensate for the extra space it normally takes up when I walk through doorways or navigate my way around a crowd of people.

Turns out, there's a scientific explanation for this. In Sandra and Matthew Blakeslee's latest book, The Body Has a Mind of Its Own: How Body Maps in Your Brain Help You Do (Almost) Everything Better (Random House; $24.95), the mother-and-son team illustrate how highly detailed areas of our brain not only correspond to different areas within our physical body, they can actually include areas outside of the body. With a malleable sense of personal space, the body maps in our brain can adjust to incorporate our clothes, our writing utensils and, yes, even our messenger bags.

Thus, when we play video games, our body maps extend to the game controller and the images on the screen; when we hit a baseball, our body maps extend to the tip of the bat; when we have sex, our body maps extend to envelop our partner.

This has huge implications for science's understanding of the mind-body connection, but luckily for the average reader, the Blakeslees break it down in a basic and understandable way. "There are books that are just for science junkies," admits Sandra Blakeslee by phone from her New Mexico home. "But we thought, right from the get-go, 'Well, everybody has a body and everybody has a brain, and it's kind of a mystery to them as to how the body and the brain communicate.' But it's not a mystery. There's all this new neuroscience that we wanted to make available to people."

Indeed, neuroscience is booming. In 2000, Blakeslee, a New York Times science writer of 40 years, attended a meeting in Los Angeles where she was introduced to Alessandro Farnč, an Italian scientist. Farnč's demonstration suggested that what we refer to as "personal space"—the surrounding area of our body that we generally do not want invaded—actually occupies real estate in the brain's parietal lobe. "Every point in that space is mapped in your brain," Blakeslee explains. "That space is part of you. You own it. And when people say, 'You're in my space,' it isn't a metaphor, it's true."

What about the musician who plays the guitar so naturally that it seems like a third arm? Or the soccer mom who drives an SUV as if it's an extension of her body? Or the amputee who still feels the phantom pain of a long-gone limb? Quoting recent breakthrough studies, Blakeslee asserts that in an area in these people's brains, the object is literally morphed into the brain's body map as a part of the physical self.

One of the book's most hands-on chapters deals with weight loss; more precisely, it confronts the battle between the body image (how we see ourselves) and the body schema (the actual physical properties of our person). Often, people who have lost weight will still "feel" fat, because their body maps remain attuned to a larger body. Getting the brain back in tune with the body is a scientifically proven way to keep weight off, Blakeslee says. "People who are overweight are not in touch with their bodies. They're actually almost in a paralytic state with their body. They don't see their body very clearly in a mirror, and they don't feel their bodies."

Using celebrities as examples, the Blakeslees outline how strengthening the body schema can successfully overcome a dysfunctional body image (Oprah Winfrey's vastly touted weight-loss victory) or capitulate to insecurity (the horror that is Michael Jackson). The authors illustrate how body-map defects are a cause for the highest-paid player in baseball, Alex Rodriguez, to lead major-league third-basemen in errors in 2006; how the golfer's plague of the "yips" caused Ben Hogan to choke on the 17th green of the 1956 U.S. Open; and why Fred Astaire dancing with his shadow isn't such a stretch, since shadows, as annexations of our physical self, register on our body maps as well.

Constantly examining body maps while going about everyday life could very well drive the average person crazy, but for those with highly attuned body maps in certain areas—pianists in the fingers, tennis players in the limbs—the Blakeslees make a startling case for motor imagery. In developed talents, the mere act of imagining the body performing certain tasks has been proven to strengthen muscles and increase performance. No wonder Kobe Bryant takes time at the foul line to imagine the ball going through the hoop.

The Body Has a Mind of Its Own covers some serious ground, particularly in the final chapter regarding the insula, a part of the brain that up until recently had been thought of as an unimportant flab—sort of a cerebral appendix. "It turns out to be considered an extremely advanced part of the brain now," says Blakeslee, citing the insula as a body-mapping mechanism of internal senses, an awesome translator of felt body state into social emotions. Problems regarding schizophrenia, chronic pain and addiction lie in the right frontal insula, Blakeslee says, and the area is just now being explored as a center for the power of belief.

Blakeslee admits surprise at learning that specific areas of the brain can trigger phenomena that she had previously written off as "whoo-whoo" nonsense—out-of-body experiences, for example. In Belgium last year, an electrode treatment suggested that an out-of-body experience can be traced to a part of the brain known as the temporoparietal junction. And though science can't yet address things like astral planes or healing touch, recent studies tilt toward the idea that where New Age mysticism and science had once been at odds, they may soon join up and hold hands.

Will we ever fully understand the human brain? Blakeslee laughs at the question. "I think, as in all science, every time you make some wonderful new discovery, it opens up another dozen questions. That's the way science works. You answer things, and then you have more questions. So, fully understanding the brain? It's so complicated. It'll take a very long time."

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|