home | north bay bohemian index | the arts | books | review

Acquired Tastes

By Michael S. Gant

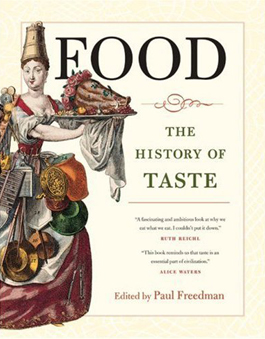

Eating begins with a need to nourish but quickly escalates to encompass issues of culture, health, status and religion—otherwise we would all be content to nosh on the occasional road kill, and there would be no Michelin stars. In Food: The History of Taste, edited by Paul Freedman (University of California; $39.95), 10 historians survey the almost impossibly large subject of cuisine, starting with our hunter-gatherer ancestors, sojourning through various regional palates and ending with thoughts on the dynamic of "novelty and tradition" that tugs at diners today. The chapters aim to expand on Freedman's injunction that "taste" be "understood not only as a flavor but the production of an impressive and artistic effect."

Alan K. Outram notes that our prehistoric sweet tooth and jones for carbs still bedevil modern dieters. Traditional Chinese cuisine, Joanna Waley-Cohen writes, depends upon "the creative combination of different forms of fan and cai," the former to fill (rice and other grains), the latter to flavor or season. In the fascinating chapter on medieval Islam, H. D. Miller notes the importance of cookbooks, "because standards of connoisseurship in Baghdad were so high"; even important generals and princes created and codified recipes.

In the Middle Ages, national cuisines began to diverge. The English started using wheat starch as a thickening agent, a practice frowned on by the French. The English, also, C. M. Woolgar notes, liked "quirky inspirations," including meatballs dressed up as hedgehogs. By the mid-17th century, heavily spiced dishes gave way to recipes that enhanced intrinsic flavors; the French, naturally, led the way (and invented dessert while they were at it). By the Industrial Revolution, mass production and marketing of food changed everyone's diets, especially the lower classes, who had been resigned to food that was "difficult to digest, often poorly prepared [and] inadvertently or deliberately adulterated," writes Hans J. Teuteberg. Alain Drouard's chapter, "Chefs, Gourmets and Gourmands," serves up an especially useful history of how the French—from Brillat-Savarin to Michel Guérard—defined high-end dining for most of the world.

The topic of taste is pretty much as broad and open-ended as humanity itself—we are what we eat, after all—so the essays here sometimes seem like they are only scratching the surface of an endless repast. The volume is liberally seasoned with marvelous illustrations, ranging from cave paintings to vintage menus to modern ads. Particularly striking is a Venetian engraving from 1571 of a three-tiered mechanical roasting spit bristling with elaborate gears and wheels. Today's backyard barbecue chef can only bow in awe.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|