home | north bay bohemian index | news | north bay | news article

Bruce Stengl

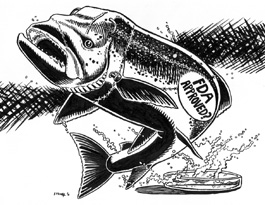

IT'S ALIVE: The makers of the Frankenfish claim that salmon farmed from genetically-modified eggs 'are exactly the same as any other North Atlantic salmon.'

Spawn of Frankenfish

Forget genetically engineered seeds—FDA approval of genetically engineered animals could be coming

By Alastair Bland

A genetically engineered salmon that grows twice as fast as unaltered fish could find its way into markets and restaurants if the Food and Drug Administration gives the creature the green light of federal approval, an action that food-safety watchdog groups suspect may be imminent.

The fish, designed by the Massachusetts biotech firm AquaBounty Technologies, is an Atlantic salmon enhanced with a growth hormone from a Chinook salmon and a gene promoter from an ocean fish called a pout. Creators of the state-of-the-art salmon, trademarked as AquAdvantage and sardonically nicknamed by its many critics the "Frankenfish," tout it as a sustainable and healthy seafood choice that could satisfy consumer demand while diverting fishing pressure from badly depleted wild stocks.

In a report released in Sept. 2010, the FDA concluded that commercial production and consumption of AquAdvantage salmon would not likely have negative environmental or human health consequences.

But many opponents of genetically engineered foods believe too many uncertainties remain about long-term impacts of genetically engineered fish to merit approval of AquaBounty's product as a human food. Environmentalists warn that the salmon could escape from captive breeding sites, compete with wild salmon for food and mates, and interfere with natural spawning activity.

"[AquaBounty is] using this idea that it's in closed containment so it won't get out," says Casson Trenor, the senior markets campaigner with Greenpeace in San Francisco. "The thing is, there's no guarantee it will stay this way. Aquaculture facilities have escapes."

Already, its creators have taken extreme caution in handling AquAdvantage salmon. The fish, which was designed in the 1990s, has only been grown to adulthood in Panama, where any escaped salmon would quickly succumb to the fatally warm tropical ocean waters. Siobhan DeLancey, an FDA spokeswoman, assured the Bohemian in an email that her agency is not considering any commercial production of the genetically altered salmon outside of Panama.

She noted, however, that this could change if growers submit applications to produce the fish in locations elsewhere, which AquaBounty seems to be counting on. Its website states that AquAdvantage salmon "are designed for on-shore facilities that can be built closer to consumers to reduce the need for energy-intensive shipping and transportation"—a vision that does not seem to include fish production six nations south of Mexico. The website also says, "The introduction of land-based salmon farms in the U.S. would spur investment into this industry in our country."

AquaBounty, whose role in AquAdvantage salmon production would be solely as an egg supplier to third-party buyers, has designed its fish such that "AquAdvantage salmon eggs only become sterile females," according to AquaBounty's CEO, Dr. Ronald Stotish, who corresponded with the Bohemian via email. These salmon will be triploids, or animals bearing three complete sets of chromosomes per cell. AquaBounty claims this sterility safeguard will eliminate risk of genetically modified genes creeping into wild salmon populations.

But test batches of eggs hatched by AquaBounty rendered as many as one fertile offspring (diploid fish with two sets of chromosomes to each cell) per 100 eggs, and AquaBounty's permit application, now under review, allows for up to 5 percent of their salmon's eggs to become fertile diploid offspring.

Researchers at Purdue University in Indiana and at the University of Stirling in Scotland have described several mechanisms that could occur in wild fish populations if fertile genetically engineered salmon escape. In their worst-case hypothetical scenarios, extinction results.

In its 172-page report, the FDA recognized an "extremely small" risk of AquAdvantage salmon escaping and establishing themselves as a manmade invasive species. This would require "escape (or intentional malicious release) of a large number of reproductively competent broodstock from the [Prince Edward Island] egg production facility." High-security physical barriers make such an event unlikely, the report says.

Even if no genetically engineered fish ever escape, says Assemblyman Jared Huffman, D-San Rafael, the mere presence of farmed salmon meat harms wild salmon by hamstringing efforts to preserve the streams in which wild fish spawn. Sen. Mark Begich, D-Alaska, has publicly expressed the same concern. Huffman recently introduced Assembly Bill 88, legislation that, if passed into law, would require any genetically modified salmon sold in California be labeled as such. Sen. Begich may introduce a similar bill which would require labeling of genetically engineered fish nationwide.

AquaBounty's representatives have balked at the idea. In an email to the Bohemian, AquaBounty's Stotish said his company favors existing federal laws which require genetically engineered foods to be clearly labeled only if the product is "compositionally different."

"Because fish grown from AquAdvantage salmon eggs are exactly the same as any other North Atlantic salmon, there is no legal authority to label the fish," Stotish says.

Indeed, the FDA stated in its September report that AquAdvantage salmon flesh —from the sterile, triploid females—is nutritionally no different than wild salmon meat and poses no foreseeable health hazards to humans. Diploid specimens which are expected to enter the market in very small numbers were not extensively studied, however, and the FDA could not rule out possible allergenicity.

AquaBounty itself has directed or overseen all research conducted on AquAdvantage salmon and provided the results to the FDA, which based its report on the data. Marianne Cufone, of the consumer watchdog group Food & Water Watch, says the testing "was very closed-door in its nature" and that the "information provided to the public has been woefully inadequate," amounting to just a handful of documents on the FDA's website.

"We're concerned because the testing [of the salmon] involved no FDA participation," Cufone says. "They just took conclusions from the very company that developed the product."

At the Center for Food Safety, regulatory policy analyst Colin O'Neil notes that AquaBounty's "application was lying on the FDA's desk for 10 years, and then the public received only 10 days in September to look at the information."

AquaBounty's reluctance to identify its fish to consumers is a red flag, according to Assemblyman Huffman.

"If [AquaBounty] believes their product is so benign, they should have no problem with identifying it," says Huffman, who worries that FDA approval of the product could lead down a slippery slope of deregulation, with California's current prohibitions on farming salmon in open-ocean pens facing increased likelihood of being lifted.

The open-ocean salmon farming industries of British Columbia, eastern Canada, and northern European nations have already devastated—and even destroyed—many wild populations of salmon, according to scientists in many nations. Yet AquaBounty's Stotish assures that his company's salmon will have net positive effects. In an email to the Bohemian, he writes, "Because the seas are fished virtually to extinction, the only way to ensure consumers get what they want is to use every tool in our toolbox."

In a poll conducted in part by Food & Water Watch, 78 percent of participants said they opposed the legalization of genetically engineered salmon as food. Though many consumers will almost certainly opt against purchasing the product if they are provided with the labeling information to do so, local chef Duskie Estes believes many others will eat it up.

"Sadly, I think there will be a market for [genetically engineered salmon]," says Estes, who, with her husband, owns Zazu Restaurant in Santa Rosa, Bovolo in Healdsburg and Black Pig Meat Co. "I don't think it would turn people off at all, even if it was labeled."

Huffman's bill is now undergoing legislative review. In all, 14 elected officials in California and several dozen House representatives and senators have spoken out against AquaBounty's fish. In Alaska, Sen. Begich has introduced a bill that aims to prohibit outright genetically engineered fish from being sold in the United States.

Estes notes that the public has final executive power in approving or rejecting food products via the money they spend as consumers. Such a selective process cannot function, however, if buyers don't know what they're buying.

AquaBounty Technologies hopes to keep it that way.

|

|

|

|

|

|