home | north bay bohemian index | music & nightlife | band review

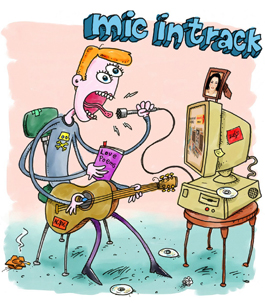

TESTING 1-2-3: What if the bizarre rap song you wrote for your boyfriend wound up worldwide?

Hello, World!

Mic in tracks, file sharing and accidental fame

By Gabe Meline

Why Is My Sister Such a Dumbass?" is the most compelling 46-second sound recording since the turn of the century, and yet its creator, an adolescent boy, is nowhere to be found. It's safe to assume he never intended a beautifully meandering ramble about his sister's underwear, her "lesbian school" and her "awkwardness in a world that is undescribable" to be heard by anyone but himself. But through a phenomenon known as "mic in tracks," his stream-of-consciousness diatribe has been heard, and loved, by thousands.

Mic in tracks represent a unique time, 1999 to 2002, when many new PCs came packaged with software called MusicMatch Jukebox, allowing a user to record into the built-in microphone on the computer's sound card. If that person forgot to name the file, as many did, it was saved under the default name "mic in track," followed by a number. But if that person also happened to share his entire audio hard drive through widespread file-sharing programs like Napster, that small mp3 made in the privacy of one's own room went out for the whole world to hear.

Naturally, in 2001, most Napster users were too busy downloading Eminem songs to care about anything labeled "Mic_in_track_033." But to a select group of enthusiasts, including Cal Poly physics lecturer David Dixon, mic in tracks represented an incredible treasure trove of found art, a readymade curation of audio vérité both fascinating and funny. Dixon began rabidly hunting down mic in track files on file-sharing sites, and each one, he says from his home in San Luis Obispo, was like a little Christmas presents.

"Once I started collecting them, I just couldn't stop," he says. "You have no idea what to expect when you download the file and start listening to it. Most of the time, it's nothing, it's literally nothing. Sometimes it's just people taping things off the radio. But every once in a while, you hear something like what I have on the site."

The tracks Dixon has collected are unbelievable (www.stark-effect.com). A barbershop quartet sings a doo-wop version of Juvenile's "Back That Ass Up." A child bangs kitchen utensils against a mixing bowl and defends Willie Nelson to the tune of the Police's "Every Breath You Take." Two girls try to hold it together singing a Christian pop song while a barking dog keeps interrupting.

"Hi, this is Miriam Halstead talking," announces a depressed-sounding teenage girl. "I like bunny rabbits. I like Satan. I like cheese and milk."

"Some of them are just really sweet, little slices of life," Dixon says. "It's like you're peeking in through someone's window." But it's more than voyeurism that makes Dixon's finds so compelling; they present an actual psychological projection, as every track drips with empathy, placing the listener right there in front of the creator's computer, to imagine all sorts of context. What happened, for example, to the relationship so poignantly eulogized in "I Love You Holly"? What compelled Casey and Liz to laugh uncontrollably while dedicating a Backstreet Boys song to Steve? Why are kids so into Insane Clown Posse?

Dixon, who once recorded plays he wrote with his friends on a reel-to-reel recorder growing up in Waukesha, Wis., was sufficiently fascinated, and started recording songs based on mic in track samples under his studio name, Stark Effect. Some followed themes, such as the "kids screwing around" genre of "Stop! I'm Watching TV!" while others, like "That Darn Bovine," sampled key phrases matched up to drumbeats, ŕ la Steve Reich's Different Trains. After they became hits on a fan forum for experimental sampling group Negativland, Dixon continued with his wealth of source material (he's got a full GB of mic in tracks on his home computer) and made an album, Mic In Track, available for free download on his site, along with 87 original mic in tracks.

"I have been criticized online in a few places for invading people's privacy by putting these things up," he says. "And I admit that I kinda am. But some of these things just need to be shared. It is a little bit troubling sometimes, especially with stuff like '14,'" referring to a vile harangue that Dixon says he was hesitant to put up online before deciding that people needed to hear how ruthless and cruel kids can be, "but I think the goods outweigh the evils in this case."

Dixon has never found any of the creators of his mic in tracks, nor have any wannabe rappers or off-key singers come forward to claim their glory. They remain, like the boy behind "Why Is My Sister Such a Dumbass?," an accidental celebrity, a nameless cross-section of American life. Is his sister really a dumbass? We'll probably never know.

David Dixon's Mic In Track project can be found at www.stark-effect.com.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|