home | north bay bohemian index | the arts | books | review

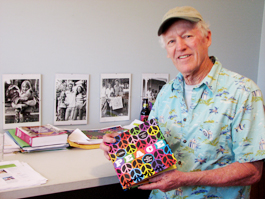

Photograph by Suzanne Daly

Emblematic: Ken Kolsbun's 'Peace' book celebrates 50 years of the symbol.

Legacy of Meaning

The peace symbol turns 50

By Suzanne Daly

On Dec. 7, 1941, a seven-year-old boy and his family gathered around the radio, listening to the horrifying announcement that Pearl Harbor had been bombed, signaling the start of U.S. involvement in WW II. As Ken Kolsbun, author of Peace: The Biography of a Symbol (National Geographic; $25), remembers it, the fear that day "was palpable. I felt how it affected the grownups in the room." Four years later, when the United States dropped atomic bombs on Japan, Kolsbun was again made fearful from acts of war. Even at age 11, he started to consider doing something to promote peace.

Some 5,000 miles away in London, activists were similarly engaged. After the German Blitz nearly destroyed their city, peace groups started to mobilize. By 1957, British peace activists had started the DAC, the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War, and conceived of the idea for a protest march.

Gerald Holtom, a British textile designer, was convinced that the campaign should have a symbol associated with it that would imprint a visual image symbolizing nuclear disarmament on the public's mind. He combined the letters from the semaphore alphabet: N, a man with drooping arms for nuclear; and D, a vertical line, for disarmament. He placed them in a circle that symbolized the earth. (The peace symbol turned upside down means "unilateral nuclear disarmament.") Holtom used white lettering on a black background for better visuals on TV and in print.

The peace symbol debuted on Good Friday, April 4, 1958, as hundreds of DAC protesters carried it on signs from London's Trafalgar Square to Aldermaston, the site of the British atomic weapons research plant, 50 miles away, joined by thousands on the way. Ten days later, a photograph of the marchers was published in Life magazine, and the symbol had its American debut. It soon took on a life of its own.

Kolsbun became aware of the symbol for the first time in 1965 and began to wear it as a button. "I felt a tinge of self-consciousness, because now I had to stand up and say what I was for," Kolsbun, now 73, says, pacing the office of his Forestville home. He started photographing peace symbols as a hobby with the help of his three young daughters, who would search the symbol out for him.

Kolsbun got in touch with Canoga Park librarian Janice Scott, whose research dovetailed with his. She had found that the John Birch Society, a fundamentalist Christian group, was promoting it as an anti-Christ symbol in pamphlets. The New York Times reported that over 200,000 requests for the pamphlet were made, mostly by other fundamental Christian churches in the United States.

By 1974, Kolsbun had accumulated enough information and photographs to put together a crude manuscript on the peace symbol's history, submitting it to publishers. After 50 rejections, he set it aside and refocused his energy. A former city planner for Santa Barbara, Kolsbun and his wife, Jannice, started Animal Town, a mail-order catalogue company selling their own cooperative play toys and games, including the bestselling Save the Whales game.

The Kolsbuns moved to Sonoma County in 1990 and continued expanding the peace project for the next 10 years. Then 9-11 hit. Kolsbun attended a San Francisco peace march a month before the war began with 200,000 other people, protesting the retaliatory bombing of Iraq. "There were many, many symbols out there," he remembers. "No one forgot about it, and it got me thinking again."

He put together a new manuscript and found a New York agent who submitted it to National Geographic, who literally agreed to publish it within two minutes of receiving it. After retooling the text with co-author Michael S. Sweeney, the book was released April 4, 2008, the symbol's 50th anniversary.

Kolsbun's happiness in seeing his work finally in print is tempered by current affairs. "The symbol holds much more power today, because it has diversified and stands for so many issues: environmental protection, nonviolence, women's rights, civil rights, brotherhood, as well as antinuclear activism," he says.

"Will some authoritarian figure who is very persuasive somehow develop the power to change the current meaning of the symbol to its antithesis, like Hitler did?" Kolsbun's tone grows more vehement. "He took a wonderful Indian symbol of peace and changed it into one of the most horrible symbols of mankind, the Nazi swastika."

Kolsbun shakes his head. "When people get the correct information, they will protect and support the symbol, and they won't let some scoundrel pervert the meaning."

Learn more and submit your own peace symbol stories at http://www.peacesymbol.com/ ]www.peacesymbol.com.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|