home | north bay bohemian index | features | north bay | open mic

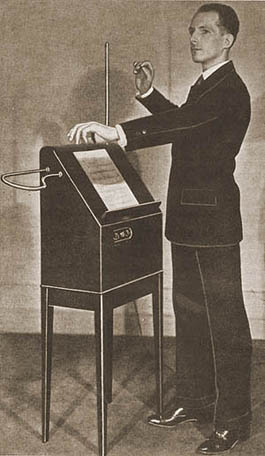

Electric Performance: Leon Theremin with the instrument named for him.

Cross Purpose

Death, theremin and the removal of the meridians

By Eliot Fintushel

The sign on my bucket says: "All Proceeds Go to the Society for the Removal of the Meridians, in Support of the Abolishment and Eradication of the Unsightly Grid of Longitudinal Lines Encircling Our Planet."

"Why not the parallels, too?" some wise guys will ask me. I'm ready for them. "They're next," I explain. "The latitude lines, because they are unconnected, have to be yanked off one at a time, but those meridians are all joined at the poles. All's you have to do is slide a hook under one of the intersections and slip those suckers off, all of them at once, like the skin off a boiled onion."

This is just a sideshow, however. The main action is my theremin. Whenever the sun shines and the mood strikes me, I set up my Moog Etherwave Pro in Santa Rosa's Railroad Square, running it and my classic Fender 85 amp off a car battery that's good for a couple of hours. In that time I can make $10 or $15 going ooeeoo and playing Rachmaninov, Debussy, Saint-SaŽns and Roddenberry. I've got backup tracks queued up on a stomp box, my "thereoke."

If a child comes by, I let him wave his arms at it—ooeeoo—and the momma's sure to toss a dollar or two in the bucket. Your older guy will give me money just for the pride of knowing what the thing is. "The Beach Boys, 'Good Vibrations,' a theremin!" he'll gush, and out comes the wallet. (I seldom bother to explain that the Beach Boys used a tannerin. Is the truth worth losing a buck or two? I doubt it.)

They come and they go. Birds sing. Clouds drift. The sun shines. Trucks doppler by. I wave my hands and pull music from the air. As long as there's a little juice in my Sears DieHard, it's not an unpleasant way to pass an afternoon.

The other day, toward the bottom of my charge and halfway through "Vocalise," a big fellow staggered into my playing field from a Chevy's across the street. He was a sturdy fellow with a thick neck and black hair neatly gooed. He wore the kind of zippered cloth coat you see on men driving tractors along country roads. He was shit-faced and half-dancing. I muted my air harp and watched him closely; the theremin is delicate, costly and rare.

"This was meant to be," he said. "You're exactly the man I'm supposed to meet. You know what I'm talking about, I can tell that you do."

Sometimes drinks will ream a fellow of everything extraneous and render him clairvoyant. I un-muted my theremin and let the big guy gesture at it. "I'm going to tell you something I want you to do," he said. "You'll do it or you won't, as God wills." He looked both troubled and ardent.

He scanned the square in one slow sweep, but lingered on the Chevy's. "Had to get out of there," he says. "Had to get some air. Daughter's birthday, 21 today. All those relatives, I know what they're thinking when they look at me. 'The drunk has to walk it off.' But that ain't it. I knew I had to come over here. You were waiting for me, but you didn't know it. I come all the way from Wisconsin, from Baraboo, to be here. Not for the birthday—don't think that. Jesus, Lord, I'm not used to big cities like this."

A gang of boys skateboarding at the far end of the lot suddenly erupted in our direction. "They feel the energy," the big guy said. "My name is Blake. What's yours?"

"Eliot."

"Well, Eliot, can you play a Hank Williams tune?"

"I'll give it a try, Blake," I said. It wasn't the tiniest fraction of what I meant, but it was all I could make myself say.

"Well, I'm just about ready. Are you just about ready, Eliot?"

"I'm ready, Blake."

Blake threw open his arms and danced and bellowed: "Yas, ma and daddy, don'tcha know, so glad, your son's a-coming home?" I followed the best way I could with long low notes in the cello range, my hand to my breast bone, because, on the theremin, that's where the deep notes are, the nearer the deeper. "This crazy world is rocking with happiness . . . sweethearts, can't you hear me praying for that great day-ay-ay?"

Blake was on fire. He was a street preacher and a brawler and a great wounded beast. He sang like a mudslide and danced like a hemorrhage.

When he was done, he leaned against me, panting. "We did it, Eliot," he said. Then: "You know who I am?" I thought he'd told me, but the fellow had more juice than a fresh DieHard, so I listened and waited. "I'm Blake Bitner, William Blake Bitner."

"Like the poet."

"Yeah, like the poet, but that's not what my momma and poppa had in mind. They didn't know a damned thing about any of that." He managed it quickly, but his red face twitched, and I knew his folks had bruised him inside. "I come all the way across the country for my son. I bet you read about him in the papers—the Bitner kid?"

I shrugged. I read the clouds. I read the crowds. I never read the news.

"Look him up," Blake says. "They say he killed a man, but he didn't have nothing to do with it—some kids at a party. Fellow was stabbed more times than Julius Caesar. Naturally, they blame the guy with a record. On top of everything else, it's the daughter's 21st birthday. The make-it-or-break it age, when you bust out or you bust."

"Which did you do, Blake?"

He gave me that clairvoyant look. "Whichever." He read me, the real me, loud and clear. "It was ordained, just like you meeting me." He ambled back to his daughter's party.

I struck my gear and hunted up a local paper. It had been front-page news: a student from San Francisco State University, a boy of 21, the make-it-or-break it age, had been stabbed to death a week earlier outside a party, nobody knew why, and four boys were being held for his murder, one of them named Bitner. His picture took up a couple of inches: a porcine, bewildered country boy in a big-city police station. Kid had a record and was currently on probation for felony burglary.

†Don't you just hate that net of meridians? We are circumscribed but won't call it real. It's like the electrostatic field around my theremin: I play it, all right, but there's nothing to touch. Waving my hands through thin air, I make children laugh and grownups drop their jaws. I am magical, invulnerable, immortal—until a beast wheels and shambles across Railroad Square to read my heart and make me harmonize. He brandishes a scythe and points a bony finger. I'm just a clown and busker. What's death to do with me?†

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|