home | north bay bohemian index | news | north bay | feature article

Back to the Land

For almost 20 years, former naval base Skaggs Island has been a dilapidated home to native wildlife and habitat— now it's finally being converted back into a nature preserve

By Juliane Poirier

Photography by Leila-Anne Cave

My first view of Skaggs Island is blurred by rain, and by the confused feeling that comes when a word applied to a land feature doesn't seem to match up.

"All this is Skaggs Island," my guide says, gesturing with a sweep of his arm. From the bridge over the Napa Slough, where I stand with U.S. Fish and Wildlife manager Don Brubaker, all I see through the rain are brackish fields and a pattern of channels reaching toward the eastern horizon.

It requires some imagination to think of this as the site of an active military base, but that's exactly what Skaggs Island was for over 50 years. Since 1993, when the base was decommissioned, wildlife and habitat have been living among the ruins—the cracked concrete, dilapidated duplexes and bombed-out buildings of the military-industrial complex. Now, thanks to conservation efforts, Skaggs Island is slowly being converted back into restored wetlands.

Unlike the Marin Islands, farther out to sea and distinctly observable as dry land surrounded by water, Skaggs Island appears to the regular observer as a marsh. It's only an island as long as the pumps are working and more than 30 miles of channels are diverting water away from a site that, if left to nature, would return to the tidal swamp it was when Spanish explorers first arrived.

An owl inside the old Navy barracks

The Spaniards, seeing the existing pseudo-islands formed by natural tidal channels, dyked and dredged waterways to drain the land for horses and hay farming. One patch of the resulting acreage remained in farming until World War II, when the Navy took over most of it for a communications base, Naval Security Group Activity Skaggs Island. There, the Navy intercepted and decoded Soviet radio communications, transmitted special-intelligence information and carried out the American military duties of the Cold War. Today, a half-century later, evidence of the once thriving military community here has all but disappeared.

Brubaker and I leave the rainy bridge and drive a few hundred feet to the entrance to Skaggs Island, its 3,300 acres now owned by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and a key piece—about 25 percent—of the 13,000-acre San Pablo Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Skaggs Island includes natural habitat for the California clapper rail and the salt marsh harvest mouse, both federally endangered species. Brubaker unlocks the main gate that keeps unauthorized visitors out until a plan for appropriate public access is devised.

But intruders get in, Brubaker explains, pointing to road reflectors shot to fragments and to pump housing recently vandalized. The pumping apparatus is the only infrastructure the Navy left behind, to keep water off of the one remaining hay farm on Skaggs Island.

"You can see where the farmed area starts," says Brubaker, pointing into the rainy distance as he drives us down the main road, where weeds push through cracks in the asphalt. Native jackrabbits and quail, along with non-native ring-necked pheasants, saunter rather than sprint in front of our slow-moving truck, as if to flaunt knowledge that they now own the place.

A snake slithers along the deserted two-mile road between the highway and the former base

But nature doesn't own the farm that comes into focus past the wild radish crowding the roadside, and neither does the public. When the U.S. government took over the land for its Naval base in 1942, paying $52 an acre, it left 1,100 acres in hay under private ownership. The deal then struck made it the Navy's job to pump water off the adjacent farm. The agreement is still binding at a present pumping cost of $50,000 a year, but the responsibility now falls to the Wildlife Service.

The Wildlife Service offered farm owner Jim Haire $6,000 an acre for the property—

$6.6 million. But Haire has thus far refused, claiming the land is worth triple that amount. Wildlife advocates, ruing that more than 80 percent of the original tidal marshes in the San Francisco Bay have been lost to development, hope those acres might someday become part of the refuge.

"We've been excited about the addition of Skaggs Island," said Brubaker. "It's an important stopover along the Pacific flyway for migratory birds. We think of it as a once-missing puzzle piece for restoration of the North Bay." Brubaker says the refuge is the result of years of work among the Navy, the Wildlife Service and a number of partners in the wildlife-advocacy community, including Congresswoman Lynn Woolsey, who introduced legislation that removed bureaucratic impediments so the property could be transferred.

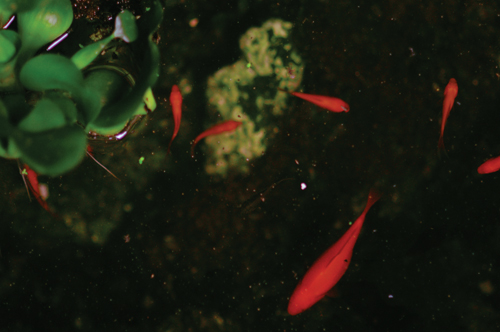

Fish thrive in a base pond

The Navy performed environmental cleanup of the site, and last year demolished more than a hundred structures, including eyesores that had fallen to ruin and been vandalized for the past 17 years. Transference became official March 31, 2011.

Yet in its heyday, Skaggs Island had been a well-tended community, as anyone can observe simply by studying the photos posted on the internet by military personnel, including one black-and-white image of a proud officer holding a trophy in the Skaggs Island bowling alley, back when 270 residents could shop at a base commissary, attend services in a chapel and go boating from a dock along a protective seawall.

As we drive past these former sites, I see—barely visible among thriving wildlife, lush greenery and water channels—a few weedy roads leading nowhere, a couple of pump sheds and the old seawall, still holding back the tide that may one day fully reclaim the eerily beautiful Skaggs Island.

Deer explore Skaggs Island while in the background stands a water tower, now destroyed

The slough gives Skaags its island status until a complete wetlands conversion

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|