home | north bay bohemian index | the arts | stage | review

Photograph by T. Charles Erickson

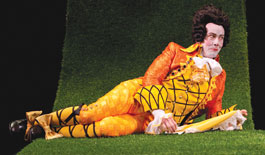

SIMP: Malvolio (Christopher Liam Moore) awaits Olivia.

Will Power

Inventive classics anchor OSF's 75th season

By David Templeton

Cross-dressing ladies. Sword-battling Brits. Vengeful Venetians in super-cool costumes. With the grand annual opening last week of the open-air Elizabethan Stage, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival's 75th summer season is officially under way. As "the Lizzie" (what the locals call the outdoor auditorium here in beautiful, theater-obsessed Ashland) throws open her doors, three of William Shakespeare's most challenging plays—including a sensational staging of The Merchant of Venice—join six other shows already running at OSF's two indoor theaters. As a treat to those who make note of such things, OSF is honoring its roots by including the two comedies that constituted the very first festival in the summer of 1935.

The commonly accepted observation that Shakespeare's comedies are conspicuously unfunny is somewhat confirmed by The Merchant of Venice (yep, that one's technically a comedy), but is soundly disproved by Twelfth Night. Crammed with outrageous accidents and desperately over-the-top characters, Twelfth Night easily supplies the most laughs of any of the Bard's stabs at humor.

As directed for OSF by Darko Tresnjak, this cleverly staged, superbly cast production multiplies Shakespeare's comedic conceits by mining the 410-year-old text for unexpectedly modern ideas and expressions. That costume designer Linda Cho has garbed the cast in outfits reminiscent of the French aristocracy, circa 1775, adds to the visual spectacle already established in Tresnjak's inspired staging. On a whimsically devised, weirdly swooping Astroturf set by David Zinn, characters slip and slide through the story, sometimes dangling from grassy pillars or popping up in secret windows like puppets in a Punch and Judy show (or jokester comics in an episode of Laugh-In).

The story is ripe with comic possibilities. Viola (Brooke Parks), shipwrecked and believing her twin brother to have drowned, disguises herself as a man, seeks safe shelter in a nearby town and promptly falls in love with the local duke, Orsino (Kenajuan Bentley). Orsino, believing his eager new confidante to be male, hires him to deliver love messages to the uninterested Lady Olivia (Miriam Laube), who promptly falls in love with the messenger.

Twelfth Night, with its cheeky gender-switching scenario, contains some of Shakespeare's most memorable secondary characters: Olivia's drunken uncle Sir Toby Belch (played with world-weary edge by Michael J. Hume); the heartbreakingly self-deluded Sir Andrew Aguecheek (a brilliant Rex Young); Olivia's criminal mastermind maid Maria (Robin Goodrin Nordli); the would-be social-climber Malvolio (Christopher Liam Moore, also brilliant); and the wisest of Shakespeare's many fools, Feste (Michael Elich, sensational).

With only the occasional wrong note—an unsettling joke about guillotines lands uncomfortably flat—this Twelfth Night is a compounding collision of disasters, spinning right to the edge of tragedy before resolving itself in a pleasantly raucous, upbeat ending.

In The Merchant of Venice, that sense of tragedy never quite dissolves, but in Bill Rauch's endlessly inventive staging, Shakespeare's controversial dark comedy is all the richer for its sense of lingering pain. Rauch handles the inherent Elizabethan anti-Semitism of the text by tackling it head-on. Propelled by Rauch's psychologically rich vision, this is not just a play about a merchant who owes a Jewish moneylender a pound of flesh.

By emphasizing and expanding the play's numerous other examples of bigotry, prejudice, suspicion and distrust—and in taking a light comedic touch with the show's various subplots about golden chests and lost rings—this Merchant becomes a potent examination of the way people judge the worth of their fellow human beings.

That Rauch has found the coherence in this stylistic clash of storylines is in itself a marvel. What pushes his Merchant to the level of greatness is the quality and clarity of the performances. Shylock (along with Romeo, the only Shakespearean character whose name has become an independent noun), is a wealthy Jewish businessman whose lifetime of abuse at the hands of Christians has left him smoldering with resentment and pent-up anger. When the merchant Antonio (a riveting Jonathan Haugen) talks Shylock into lending him 3,000 ducats, which he then lends to his friend (and apparent secret love interest) Bassanio (Danforth Comins), he berates the moneylender for his practice of charging interest.

On a whim, Shylock instead offers to accept a pound of Antonio's flesh as guarantee on the loan. When Antonio eventually defaults, an incident that coincides with Shylock's daughter stealing 2,000 ducats and eloping with a Christian, the heartbroken Jew sees a rare opportunity to win out over his oppressors. He demands payment and takes Antonio to court to collect his ghastly collateral.

Bravely and beautifully played by Anthony Heald (in six seasons at OSF, he's never been better), this Shylock is certainly monstrous, but understandably so. While the Christians he confronts all blame his Jewishness for his actions, Shakespeare shows Shylock's human heart crying out for justice, and allows us to see what they do not: that their casual everyday cruelties are ultimately no more acceptable than is Shylock's one, long-delayed explosion of rage.

Henry IV, Part One, with its introduction of Shakespeare's beloved Sir John Falstaff, is the story of a future king, Prince Hal (John Tufts), right at the moment he evolves from hard-partying youth to inspirational leader. As written, the play is like a tasty cupcake buried in too much icing. The simplicity of the story is easily lost amid so much talk and clever wordplay. The festival has established a reputation for making even the most difficult of Shakespeare's histories interesting and gripping. Unfortunately, under the placid direction of Penny Metropulos, even with excellent performances by Tufts, David Kelly as Falstaff, and Kevin Kennerly as Hal's joyfully aggressive rival Hotspur, the production demands quite a bit of audience effort and concentration in order to reap its many rewards.

Following last season's Pleasantville-esque staging of The Music Man (and overlapping OSF's recent announcement of a major grant to develop four original musicals), the infectious 1963 confection She Loves Me (by Fiddler on the Roof's Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick) should allay any fears that the company's dalliance with musicals is an attempt at pandering to popular tastes. With this mostly forgotten charmer, remarkably well directed by Rebecca Taichman, OSF proves itself a gutsy and sly interpreter of the American musical artform.

Based on the play that eventually inspired the movie You've Got Mail, She Loves Me is the sweetly hilarious story of two shy salespeople who fiercely dislike one another, not knowing that each is the other's longtime anonymous pen pal. With its theme of secret identities and the ultimate triumph of love, this tuneful must-see delight is nothing short of Shakespearean.

OSF runs through Oct. 6. www.orshakes.org.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|