home | north bay bohemian index | news | north bay | news article

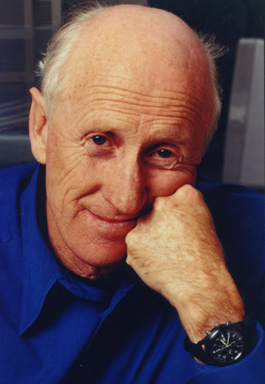

THE INDESTRUCTABLE MR. BRAND: Stewart Brand is impossible to pigeonhole.

Wild Trip

The world's oracle enigma . . . lives on a tugboat in Sausalito?

By P. Joseph Potocki

He's just back from TED, the inaugural and widely publicized Technology, Entertainment and Design roundtable for Hillary Clinton's State Department. He's fresh off a lively debate on NPR's Science Friday concerning the future of nuclear energy. And still, Stewart Brand is hardly a main-street household name.

Readers of a certain age and cultural bent might recall Brand for founding, editing and publishing the National Book Award–winning Whole Earth Catalog, or for references to him in Tom Wolfe's New Journalism psychedelic classic The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Brand is perhaps the late 20th–early 21st century's most effective and unorthodox visionary. He's a 70-year-old white guy living on a tugboat in Sausalito who engages, counsels and bills the world's wealthiest and most powerful by playing them through "scenarios" at the Global Business Network (GBN) he helped found. Less well-heeled folk, those with stakes in the artistic, cultural, technological, intellectual and political etherscapes, might well know of and either love or dislike Brand, but should they be 45 years of age or younger, they likely don't know one damn thing about him.

Brand is an Exeter- and Stanford-educated biologist and army-trained Merry Prankster who conceived and organized the Trips Festival, three days of seminal San Francisco '60s madness featuring Owsley acid, experimental film, dance, guerrilla theater and colorful amoeba-like liquid projections, all melded together with Big Brother and the Holding Company, the Grateful Dead, the God Box, spacemen, a "masturbation sermon," Allen Ginsberg and the amplified ongoing rant of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest author Ken Kesey.

The Trips Festival also featured Brand's own presentation of his multimedia roadshow, America Needs Indians. To create his show, Brand spent time on Warm Springs, Blackfoot, Navajo, Hopi, Papago and other Indian reservations. These days, Brand, via GBN, works with tribes like Dow, Bechtel, ExxonMobil, Microsoft, PG&E, Monsanto and CitiGroup.

First published in 1968, Brand's Whole Earth Catalog inspired a younger generation to head "back to the land" in order to pursue simpler, more naturalistic and organic lifestyles, leaving crowded cities and consumer-addictive suburbias behind for good. Ironically, Brand now finds the unprecedented and accelerating degree to which humanity is fleeing rural ancestral homes for gargantuan squatter cities as a positive and encouraging trend—and, what's more, because he feels it's the way to feed these masses, he's become an enthusiastic proponent of genetically modified foods.

As a Stanford biology student back in the 1950s, Brand came under the tutelage of entomologist and renowned ecologist Paul Ehrlich. Erlich's book The Population Bomb inspired Brand to organize a public fast highlighting spiraling world population growth, the consequence of which, Ehrlich forecast, would mean that "hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now." Brand says he learned an important lesson from the shattering of Ehrlich's crystal ball; in fact, the Brand of today goes so far as to suggest that we may require more, not less, people living here on planet Earth.

Brand has long been an advocate and promoter of carbon-free energy development and was an early opponent of nuclear energy. However, for the past few years, he's fashioned himself into an environmentalist lightning rod. He now advocates for the development and proliferation of nuclear energy plants across the globe. "Micro-reactor designs are coming out fast," Brand enthused recently on NPR. "These are down [to the] 25 megawatt, 35 megawatt, 50 megawatts level. They cost about a million dollars a megawatt. They're quick to build. They look like a whole different animal than the 1.2 gigawatt [or] the 1.6 gigawatt reactors."

Brand, who declined to be interviewed for this essay, seems to delight in these shifting positions, self-identifying, for example, as an environmental heretic. During the June 5 NPR Science Friday debate, Brand explained why he flipped on the nuclear energy issue after addressing human potential for harnessing solar power. "If we get solar coming down from space, where it's always on, then it's base-load power," he noted. "But it's really expensive to get there, unless we start mining asteroids. . . . So it looks to me like we're stuck with nuclear as the low-to-no-carbon source of base-load power for some decades to come."

Progressive critics have flogged Brand for his suggestion that all the world's spent nuclear rods be reprocessed at a single site, from which fuel would be redistributed. That idea, they say, is a recipe for totalitarian control. Brand, however, says our imminent and growing coal-carbon crisis eclipses that of nuclear waste, proposing that such waste either remain in dry-cast storage or be sent off to an underground salt area in New Mexico.

What Brand doesn't mention, according to Sourcewatch and the Center for Media and Democracy, is that he may not be an honest broker on this topic. They point out that over a dozen major players—those who stand to make billions should the nuclear phoenix rise again—pay Mr. Brand for his GBN services.

While convolutions and contradictions seem his stock in trade, and while a host of progressives find his latter-day causes disturbing, or even abhorrent, what's most intriguing is that each of Brand's flip-flops both make and don't make perfect sense, depending upon one's perspective. In fact, much of the controversy and confusion over his opinions derives from the simple fact that Brand deals most prominently in the future—and it hasn't yet arrived.

In a 1972 article he wrote for Rolling Stone magazine titled "Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums," Brand noted that "all historians understand that they must never, ever talk about the future. Their discipline requires that they deal in fact, and future doesn't have any yet." So since the future doesn't have any facts, just who's to say what it will look like?

Well, Stewart Brand, for one. Brand minced few words when, in 2004, he wrote, "Over the next 10 years, I predict the mainstream of the environmental movement will reverse its opinion and activism in four major areas: population growth, urbanization, genetically engineered organisms and nuclear power."

Predictions have evolved into an industry for Brand. Thirteen years ago, he cofounded the 501c3 Long Now Foundation, dedicated to "creatively foster long-term thinking and responsibility in the framework of the next 10,000 years." In 2001, he and Wired magazine's Kevin Kelly spun out their Long Bets project from within the Long Now Foundation. At Long Bets, participants predict and wager on the future, publicly, using their real names.

One contributor's prediction foresees Google Street View becoming a "Grand Theft Auto–like" gaming platform. Wagers include an $800 bet that Sasquatch will be discovered by 2025, and a $400 bet that in the year 2108 "an independent, sentient artificial intelligence will exist as a corporation, both providing its services as well as making all financial and strategic decisions."

With Brand's youthful, unbounded energy, curiosity and ideas spinning constantly in motion, his many-faceted projects were destined to be writ large in the canon of the countercultural 1960s. He was present at the founding of both the ecology and the back-to-the-land movements. It was Brand who largely popularized the metaphor of tools—from reliable ancient and low-tech tools to cutting edge technologies of the mind; from planting organic seeds to planting space colonies on distant planets.

When the time arrived, Brand likewise rode the pulse of the '70s and '80s. He wrote, organized, designed and taught. He founded the WELL, the world's first cyber community, and in the twilight of Reagan, he cofounded the Global Business Network. Almost antithetically, in 1990 Brand joined the board of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which fights both large corporations and the government, advocating for personal freedom on issues including digital communications, free speech, privacy, anonymity and consumer rights.

Brand abetted the birth of personal computing. He helped transform the internet from an obscure government project to an ever more powerful array of communicative lightning strikes. Brand's been active in emerging media and technology developments all along. He's a creative gaming visionary and an intellectual gadfly, placing bets, embracing politics, publishing and establishing the School of Compassionate Skills. And he has engaged and become friends with many of the planet's movers and shakers by projecting his talent as an envelope-pushing impresario.

Now 70, Brand still attracts great minds of the modern era. From cybernetics pioneers Norbert Wiener and Gregory Bateson to anthropologist Margaret Mead and futurist Buckminster Fuller decades ago; to the Long Term Thinking seminars he's hosted since 2003, featuring the likes of musician Brian Eno, cyberpunk writers William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, and philosopher and political economist Francis Fukuyama, Brand has exhibited an uncanny knack for connecting with the world's best and brightest.

One could place an enormous question mark around the being that is Stewart Brand, much like many puzzle that two members of the Grateful Dead, hippiedom's most revered band and Brand's own countercultural contemporaries, belong to the ultraconservative, Republican, corporate and military-industrial Bohemian Club. But if anything's clear in referencing Stewart Brand, it's that labels like left, right, conservative, progressive and radical are meaningless. Taking an extremely long view of the world's challenges may not actually provide accurate snapshots of the future, but taking the long, long view surely eats through orthodoxy like acid.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|