home | north bay bohemian index | the arts | visual arts | review

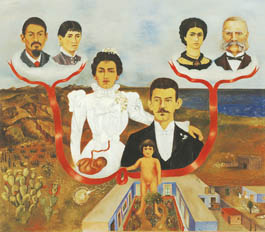

© Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY; artwork © 2008 Banco de México, Trustee of Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust

Rooted: 'My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree),' 1936.

Dogs and Monkeys

SFMOMA salutes Mexican artist and icon Frida Kahlo at 100

By Richard von Busack

At the first American show in November 1938 at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City, critics noted the "primitive but meticulous technique" of a new artist. Timeobserved, "Little Frida's pictures" have the "playfully bloody fancy of an unsentimental child." B-list Algonquinist Frank Crowninshield later described her as "the most recent of Diego Rivera's ex-wives . . . apparently obsessive with an interest in blood"—"As if they didn't have blood in their own veins," to quote Pauline Kael's remark about critics' blinkered reaction to Mexicanophile director Sam Peckinpah.

Now Frida Kahlo is honored in a centenary show of 42 paintings at SFMOMA. It's a knockout. Seeing "Frida Kahlo" is like visiting the Musée Picasso in Paris and getting the full force of that one particular talent. The difference is that Picasso's force was spread over many media and artistic stages. Kahlo's force is more tightly focused. Her study is the study of herself—that sensual hirsute face, the joined brows like the silhouette of a blackbird in flight, her face slightly turned or more often full, shining in its sense and sensuality as well as its suffering and isolation.

The show is co-curated by Hayden Herrera, whose book Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo is still essential reading. Organized at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the exhibit is augmented with an exhibit on Frida and Diego's relatively calm times in San Francisco. Key to this show is one of the treasures of SFMOMA, the 1931 painting of the then-cozy couple. "An elephant and a dove," moaned her parents.

Mostly what we see are small autoretrato—self-portraits, small panels, usually oil on Masonite or copper, sometimes tin or aluminum. The works have a Medieval flatness that recalls Henri Rousseau. They get richer and more intimate as Kahlo grew in confidence. Being a patient for most of her life led Kahlo into anatomical interest. The largest painting on view, 1939's famous Two Fridas, shows two dissected secular hearts, rather than sacred ones. Underneath her own romanticism, Frida must have realized that love is physiology.

In another retablo, Frida records her sufferings at the Henry Ford Hospital in the blistering-hot Depression summer of 1932. The division between the sick and the well appears at its most drastic in 1945's Without Hope, where Frida is paralyzed, crammed full of rotten meat with a funnel. Her dessert will be a Oaxaca-style sugar skull, with her name on its forehead.

Some question whether to place the importance of Kahlo as a world or a Mexican artist. Seeing the power of this show, I prefer the former. However, in Mexico, they make real saints out of secular figures. Jesús Malverde, a bandit hung in 1909, is still prayed to by the smugglers of today. Some travelers ask a regional saint called Juan Soldado for safe transit across the border. Frida will be getting her own prayers before long. If some blasphemer painted a mustache and a unibrow on the Virgin of Guadalupe, who wouldn't understand?

'Frida Kahlo' runs through Sept. 28 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; see www.sfmoma.org or call 415.357.4000 for details.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|