home | north bay bohemian index | music & nightlife | band review

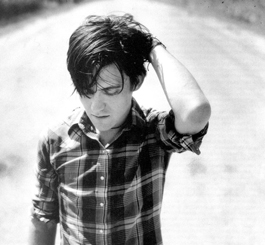

Big for his Britches: Conor Oberst's new self-titled disc is a so-what-er.

Steppin' Out

Did Conor Oberst really need to make a solo record?

By Gabe Meline

Last year, I was at O'Leavers Pub in Omaha, Neb., an old haunt of indie wünderkind and Bright Eyes sensation Conor Oberst. People in Omaha are very friendly, and while enjoying the Fugazi on the jukebox, the easy-listening LP decór and the complete lyrics to L. L. Cool J's "I Need Love" graffiti'd on the wall, I asked my fellow pub-goers about Oberst. Every one told a variation on the same story.

"That guy," said one particularly whiskey-mottled barfly, "slept with every girl in town."

Whether or not it's true—small towns being small towns—the rumor only adds to the enigmatic reputation of Conor Oberst, 28, who next week releases his first major solo album outside of the Bright Eyes steam train that's provided one of the most illusory and fleeting catalogues of American music in the last 10 years. Unfortunately, that train has pulled into a station called Blandsville, and Conor Oberst is a predictable layover in safe territory. The sharp edges of idiot and genius on either side of his previously dichotomized spectrum have been shaved smooth, and what's delivered is an album as lazy and as flat as Oberst's boyish bob.

I always root for Oberst, even though his records are full of pretentiously calculated "spontaneity"—taxing field recordings, long interviews with himself and ingratiating, pointless storytelling—because, on the other hand, each album has contained absolute gems. "Let's Not Shit Ourselves (To Love and to Be Loved)," "Landlocked Blues"—these are songs that will be sung 30 or 40 years from now, and others, such as "When the President Talks to God," have already made history. (His short-lived 2002 side project, Desaparecidos, warrants an entire separate column.)

Recording since he was 13, Oberst has grown up in public with fame thrust upon him quickly, manifesting in strange ways. At a recent Omaha show, for example, Bruce Springsteen invited Oberst up onstage to sing "Thunder Road," which Oberst thoroughly butchered. There are hundreds of thousands of people who'd give their right arm to sing with Springsteen onstage, and Oberst didn't even bother to memorize the words.

In his own material, though, he's exuded a strong sense of believing his own prominence. When this works, it's great; when it doesn't, he delivers insipid ideas ("If you want to see the future / Look into a cloud") with awkward conviction. Often, he'll become so immersed in the "truth" in his lines that he'll punctuate them with screaming, passionate agreements with himself, such as "That's a fact!" or "Oh yeah, we will!"

So here we have Conor Oberst, recorded in Tepoztlán, Mexico, with plenty of free time and open air. This is a bad thing. Oberst excels best when put under constraints, be they of time or of the heart, and the scenes he's conjured—of sleeping on the beach, refilling his canteen, watching the fireplace—rest on their own breezy banality instead of his talent for insight. Musically, the record is a stab at mediocre alt-country; it makes me miss the jagged ridiculousness of his early lo-fi efforts even more.

"Sausalito," for example, moseys over a loping bass line, with Oberst singing about living easy on a houseboat, and "I Don't Want to Die (In the Hospital)" is a bona fide roadhouse romp that finds Oberst ditching any idea of musical originality and latching on to the Bakersfield sound hook, line and twang. "Help me get my boots back on," he sings, "I gotta go, go, go, 'cause I don't have a home."

Elsewhere, Oberst's imitative voice sounds at times exactly like Tom Petty, Gordon Gano or even, in the spitfire consonants accented on "Cape Canaveral" or "Get Well Cards," a little like Eminem. This is also a bad thing. In the record's token screamed agreement with himself—"ˇClaro que sí!"—he sounds less like the eruptive Oberst we've come to know and more like the Frito Bandito. Maybe it's a joke?

Oberst's Townes Van Zandt influence comes to the fore on "Milk Thistle," a fragile song which is the album's best. "If I go to heaven, I'll be bored as hell," he sings, "like a little baby at the bottom of a well." It's a line so good, he uses it again to close the record, and one can't help but remember when lines like this whizzed in and out of him at lightning speed.

Longtime fans of Bright Eyes might find reason to worry, but let's hope Conor Oberst isn't a sign of Oberst's future direction. It's a casual vacation, nothing more; he flew down to Mexico and recorded some songs, that's all, and I'm willing to bet that the girls down there are prettier than the ones at O'Leavers.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|