home | north bay bohemian index | news | north bay | news article

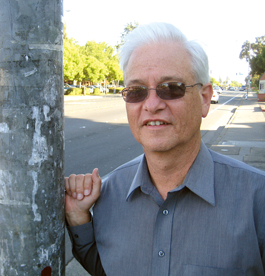

Photograph by Gabe Meline

SEEN THE LIGHT: Santa Rosa Public Works director Rick Moshier leads a unique energy-saving program that casts light on unnecessary spending for streetlights.

Darkness on the Edge of Town

Why Santa Rosa public works director Rick Moshier is on a campaign to turn off the lights

By Gabe Meline

It's not that Rick Moshier hates streetlights. Several years ago, just for fun, he made a construction-paper collage of a nighttime street scene, with tall lamps shining brightly on the empty streets, and won a ribbon for it at the county fair; now it hangs prominently on the wall of his office as the director of Public Works with the city of Santa Rosa.

But Moshier, who has worked for the city for 28 years, does hate waste. To that end, he has recently implemented a radical cost-cutting program that will turn off more than half of Santa Rosa's 10,000 streetlights for good, with even more lights placed on timers, set to go dark nightly between midnight and 5:30am. The first phase in the junior college area has already been completed, and in the next two years, Moshier says, the lights-out program will cover every neighborhood in the city.

"The energy bill for the streetlights is a big number—it's $800,000 per year," Moshier explains. "As the city over the years would have budget stress, I would be told to cut my budget. But that was a number we couldn't cut. It was just there." Instead, Moshier, who recently saw the public works budget cut by 23 percent, was forced to ignore potholes and reduce maintenance on storm drains, not to mention having to lay off the people who would normally perform those jobs. "It was getting pretty severe," he says.

Moshier estimates that turning off streetlights can cut that energy bill in half, down to $400,000 or more. "That's the goal," he says. "Well, it's more than the goal—that's what we committed to do. We cut that much out of my budget. I mean, I gave away the money. So we're committed to saving half our energy bill."

Not all streetlights in Santa Rosa will be shut off. The lights will stay on for high-density areas such as Fourth Street, at all intersections and crosswalks, beneath the Third Street underpass and along the Prince Memorial Greenway, and public feedback may dictate further areas stay illuminated. Due to a recent car break-in on Carrillo Street, the decision was made to leave one light on in the middle of blocks longer than 600 feet long.

Though budget cuts and energy savings have swept the nation, no other city in the country is turning off such a large percentage of its streetlights, which are traditionally considered to equal public safety. National outlets such as USA Today and Fox News have been calling Moshier's office, asking why a city would turn off its streetlights. He instead chooses to ask why so many were turned on in the first place.

"The statistics and the research that the police department has done find that there isn't a correlation between more light and more safety," Moshier says. "It's just something we evolved into. At first glance, it makes common sense, having more light; it resonates. We just incrementally got used to more and more light, and we came to expect it."

Moshier cites a handbook that all cities receive with suggested standards for lighting. "They say that you should only have so much variation from the darkest point to the lightest point, and that you should have some light everywhere," he says. "When you add it all up, man, you have to put in a lot of light!

"We don't need it in most locations."

It's not surprising that the 50-year-old handbook, written and distributed by General Electric, aggressively encourages the use of lights. Moshier thinks it's an outdated thought process developed for larger cities like San Francisco by an industry association that stood to profit from more lighting, and it's simply been allowed to run for too long. "Fifty years later," he says, "we're all concerned about greenhouse gases and we're all concerned about money, and you look around for what you can do about those things, and this is one of the fairly big and, I think, relatively painless solutions."

Nearby cities have taken notice. Nader Mansourian, assistant director of Public Works in San Rafael, has certainly wrestled with his own budget cuts. "We had layoffs and we had early retirements. We won't do any more pavement repairs. We'll just fix the potholes, unless it's an overlay job," he says, but he's never considered turning off any of San Rafael's 4,400 lights. "I would imagine we would save $5,000 to $6,000 a month," he estimates, "and for that much money, I would rather have the safety."

In his time at the Public Works department, Moshier has worked directly on the restoration of Santa Rosa Creek, the Prince Memorial Greenway, bike lanes on Mendocino Avenue and Montgomery Drive, smart-technology traffic signal software and hybrid city buses. Many in his department ride bikes to work, one employee coming from as far as Novato. Turning off streetlights fulfills that same environmental need, he says. "We've got to do all the small things, everything we can do about greenhouse gas, to even have a prayer of being on track," he says.

"We're hoping, and we think that this is something the community will accept. We don't expect everyone to like it, we don't expect everyone to be a proponent of this. We hope for people's patience, and I hope people can acknowledge that we're taking on a difficult task for the right reasons and have a little understanding that this is a worthwhile thing to be working on."

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|