home | north bay bohemian index | features | north bay | feature story

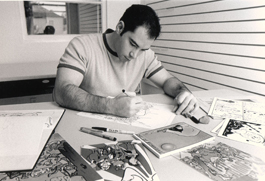

Photograph by Pamela Gerard

CLEAN LINES: Alexis Fajardo is one of four emerging cartoonists who work for 'Peanuts.'

Drawing Power

Schulz Museum's guest cartoonist program inks in new talent

By Gabe Meline

From the street, the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa appears as a monument solely to the work of one man. With permanent displays of original "Peanuts" strips; revolving shows themed around baseball allegories, musical tastes and the philosophies of "Peanuts"; and a recreation of the studio where "Peanuts" was drawn every day for over 50 years, the museum points grandly to Schulz, Schulz and Schulz.

It's all a little overwhelming. It's also safe to say that if that were all the museum focused on, even Sparky would have hated it.

Because there's another little-known side to the Schulz Museum, one that's not often on parade. Just as the museum is devoted to protecting the legacy of the famed "Peanuts" creator, it's almost equally as devoted to supporting relatively unknown, emerging cartoonists who still draw notebook sketches in coffee shops and publish their own work with sometimes gritty and dark themes far removed from the feel-good warmth of Schulz's iconic characters. And Schulz wouldn't have had it any other way.

"Any cartoonist will tell you this: he always had time for cartoonists. He nurtured them, he listened to them, he was supportive of them," says museum director and longtime Schulz friend Karen Johnson. "In a way, [this] program is continuing what he really did in life."

In the intimate setting of the museum, visitors have the chance to see cartoonists at work, to ask questions and to discuss the art form. This has manifested itself in high-profile ways, with appearances by Lynn Johnston of "For Better or for Worse," Dan Piraro of "Bizarro" and an upcoming Oct. 18 appearance by Berkeley Breathed of "Bloom County" and "Opus." The spotlighting of young artists who are self-published or under the radar is not as well known, but no less important.

Jessica Ruskin, the museum's education director, credits Schulz's widow, board president Jean Schulz, as a fierce supporter. "When I came on as the education director," Ruskin explains, "Jean said, 'This is the backbone of what we do. This is the heart of the museum's programming. It has to stay.'"

But what about local cartoonist Trevor Alixopulos, whose newest book wrestles—in rather clear imagery—with humankind's need to fight, drink, kill, do drugs and have sex? Isn't that at odds with the innocent tone of Schulz's work? Ruskin, who travels to comic conventions far and wide every year to find cartoonists for the museum's residency program, doesn't think so. "I feel like we're not here to censor anybody," she says.

"It's topics we're all used to seeing, taken up in novels and literature and newspapers. Why not see them taken up in cartooning?" Ruskin says. "We had Keith Knight here, with his recent book I Left My Arse in San Francisco. His work is sometimes very edgy, it has profanity in it, and for Jean, it's not even a question at all. It's not about the content. It's about who he is: he's a great cartoonist doing great work."

Paige Braddock, who authors the nation's premier lesbian comic strip "Jane's World," handles the vast world of Schulz's licensing and copyright. Schulz was always supportive of what he called Braddock's "appealing characters," and Braddock says that with Schulz, content was rarely an issue. "For him, it would be the craft itself, the quality of somebody's art, execution, storytelling," she says. "Some of the finer points, like lettering, the craft of using a pen, I think he appreciated. He was really old-school."

Tucked behind the museum, Braddock's office at 1 Snoopy Lane is the also home of three other cartoonists. By day, it's a fine place to broker licensing deals with German marketing companies who want to put Snoopy on a lunch box. But at night, it's a downright magical place for cartoonists to work. This is, after all, Schulz's old studio, where he drew "Peanuts" every day for over 30 years.

On a recent nightat the studio, Trevor Alixopulos admires Schulz's crow quill pen and inkwell, displayed on a shelf. He pulls out his own pen. With its metal nib, it's not that much different from Schulz's, except that Schulz's grip is cork. Alixopulos' is made from layers of duct tape.

"I've tried to use crow quill pens, like those right there, and I've got no facility for it," says Alexis Fajardo, a fellow cartoonist who works at the Schulz studio. The two are here tonight to discuss their art, and go on to talk line thickness, Japanese brush pens, controlled chaos and the Zen of drawing. "It's messy," Alixopulos admits. "I'm covered in ink all the time."

Alixopulos, 30, and Fajardo, 32, both have upcoming appearances at the museum, and while both are incredibly talented, their styles are vastly different. Fajardo's Kid Beowulf is a cleverly historical prequel to Beowulf, full of swords and kings and dragons. Alixopulos' latest, The Hot Breath of War, is a surreal rumination on war in modern society, peppered with foreign ambush, nightclubs and one-night stands. Fajardo prepares his pages with blue pencil on Bristol board before inking his panels; Alixopulos draws directly in ink to drugstore sketchbook with no borders.

Despite the thematic and stylistic gap, the two artists share the opinion that cartooning is widely misunderstood. "I say that I'm a cartoonist," Fajardo explains, "and I expect people to say, 'Oh, wow, you're a cartoonist, that's kick ass!' But lot of the time, it's just general confusion. They think it's insulting if they call you a cartoonist."

Though movies such as Dark City and Persepolis have elevated the term "graphic novel" in the public's mind, Alixopulos says the public image of comics is still mangled by superhero comics and the clichés thereof, such as the comic-book-store guy from the Simpsons. "It's really not too far from the truth," adds Fajardo. "But that's more of the traditional, dungeon-esque comic-book shop of the '80s."

Comics have come a long way since then, when DC and Marvel ruled; specifically, in the early '90s, coinciding with the rise of DIY subculture and its attendant fanzines, cartoonists began photocopying their art and stapling their own books to sell at comic conventions. It was a boom not just in quantity but in style, as small comics gained in popularity to expand the parameters of the medium.

Both Fajardo and Alixopulos have paid their dues at the Xerox machine, preparing for conventions. They've both collected rejection letters from publishers and syndicates. Fajardo's work was once even shredded in a harsh letter of criticism from Johnny Hart, the overtly religious conservative cartoonist. ("He had some salient points," Fajardo admits.)

In any other area of the country, Fajardo and Alixopulos would rely on independent bookstores and comic-book stores for in-person appearances. The Schulz Museum carries a special mark of prestige, and in Alixopulos' case, the request to appear at the Schulz museum was especially flattering. His work, after all, is rather unusual. "People usually ask, 'What is it about?'" he says.

By contrast, Debbie Huey's cartoon series "Bumperboy" falls more in line with the innocence of "Peanuts." She hesitates to describe her works as a children's comic, as most people seem to do, but calls the simple, bulbous Bumperboy a character "for that 'all ages' label, definitely appropriate for the kids." Huey, 30, lives in Redwood City and was recently invited to the Schulz Museum for an appearance.

"I'm one of the few comic creators today who did not read comics as a kid," she says. "Occasionally, I would read newspaper strips like "Garfield." But I didn't actually search for the newspaper funnies." One day in 2000, she created Bumperboy in her sketchbook, and the image stuck. She drew the character every day afterwards, and refers to "him" as one might speak of a good friend.

In 2002, she brought her self-published mini-comics to the Alternative Press Expo in San Francisco, and a love affair was born. Two books followed, and throughout, Huey has continued to work with ink instead of a computer. "All you need is just a pen and paper to create comics, and there's a certain magic about that," she says.

Approached by Ruskin at a comic convention in San Diego, Huey was thrilled at the invitation to appear at the museum. But, she notes, it points to a larger thread of the cartooning world, a circle of encouragement. "I think that's one of the awesome things about the comics industry," she enthuses. "Most everyone is trying to support each other and helping spread the word of comics, and to improve comics."

Which echoes the spirit of Charles Schulz, who, based on those who knew him, was one of the biggest supporters of all. "I always have the feeling," says Johnson of the museum's outreach efforts, "that he's looking down saying, 'This is great! Giving all these people opportunities in my name!' I really believe that."

The guest cartoonist program is an ongoing series. Trevor Alixopulos appears on Saturday, Sept. 20, at 4pm, and Alexis Fajardo appears Sunday, Sept. 28, at 1pm. Charles M. Schulz Museum, 2301 Hardies Lane, Santa Rosa. Free with museum admission. 707.579.4452. For an artist-on-artist discussion with Alixopulos and Fajardo, see [ http://www.bohemian.com/bohoblog ] www.bohemian.com/bohoblog.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|