home | north bay bohemian index | sonoma, napa, marin county restaurants | review

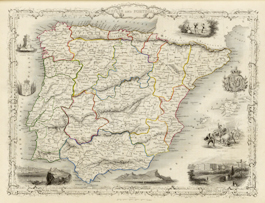

Old Yerp: As the French have protected the name of Champagne, so too do the Portuguese seek to protect Porto.

Essay: Porto isn't the same as port

Like Champagne, makers of the fortified wine known as port are fighting for a designation that demands Portugal and capitalization be part of the honors.

By Alastair Bland

The most famous fortified wine of all, Porto is as Portuguese as a Lodi Zinfandel is Californian. So how must the Portuguese feel now that wineries around the world have seized the word—which is, of course, the name of a city in northern Portugal—dwarfed the p, amputated the o and slapped the four remaining letters onto millions of bottles of a very sticky, ruby-red fortified dessert wine?

Raul Riba D'Ave, sales and marketing manager for Fladgate Partnership, a conglomerate of four respected Portuguese wine brands in Vila Nova de Gaia, across the Douro River from the city of Porto, is just amused.

"Your wine is an imitation," he laughs good-naturedly during a recent phone conversation. "It's actually forbidden to use that name outside the Douro region. You guys are breaking the law."

Porto originated as an export product for the British in the late 1600s. Vintners along the Douro River began supplying the wine, which often embarked on a second bout of fermentation in transit, leading to popped corks and cracked bottles. To alleviate this problem, shippers began adding brandy before bottling to kill the active yeasts and prevent further fermentation. As time wore on, this fortification process began to occur before shipment, often upstream in the wine country. This alcohol boost stopped all fermentation of the natural sugars in the grape juice, and the earlier this process was enacted, the sweeter the wine. The British liked the trend, winemakers never looked back, and today Portugal churns out 10 million cases of Porto per year.

Porto and port come in two major styles, tawny and ruby. The tawnys have been aged in barrels for years, have oxidized, evaporated, turned brownish-orange and exchanged most of their original fruit qualities for such delicious flavors as caramel, vanilla, tobacco, hazelnut, dried figs and velvet. (I've had velvet before, and it's quite good.)

Ruby ports are bottled-aged. Oxidation and other barrel effects do not occur, and thus these wines retain their brilliant colors and massive fruitiness. Vintage ports, made only in exceptional grape seasons, are rubies, bottled up as soon as they're ready so as to encapsulate the essences that defined that particular season.

Since tawnys bear a less terroir than rubies, they are easier to imitate, says D'Ave. But is anybody in California really imitating the Portuguese?

"Portugal has set the standards for port, and so it makes great sense to watch them and taste what they make," says Marco Cappelli, dessert winemaker for Swanson Vineyards in Rutherford. "But we're like the Australians, and we're making our own unique style of fortified wines. Port from Portugal and port from here are different animals entirely, and we should appreciate each for what it is."

Andrew Quady, owner and winemaker at Quady Winery in Madera, produces a line of dessert wines, including two that are red, fortified, sweet and strong. Quady calls them Starboard, a trademarked name.

"One of the great things about the wine business is that we mostly respect what others are doing," he says, "and nomenclature is very important for those who have been doing something for a long time. Over here, we haven't, and we can't just go and call some wine that we began making a few years ago 'port.'"

In fact, Quady feels that even comparing port to Porto is pointless. "Californian port makers need to look at their wine for what it is," Quady says. "The only things our fortified wines have in common with real port is that they're red, sweet and 20 percent alcohol. They're usually not even made with Portuguese grapes."

Actually, Quady does make one of his Starboards from four traditional Porto grapes, yet he admits that the wine is nothing like the product from Portugal—terroir at work—and he says that for a California producer to come out with a product that matches a true Porto in flavor, body and aroma is nearly impossible.

Mick Schroeder, winemaker at Geyser Peak in Geyserville, makes two fortified red wines which brazenly go around calling themselves "port."

"If it's not port, then what do you describe it as?" Schroeder asks. "If you had to call it a 'California fortified red dessert wine,' I'm not sure consumers would even know what it is."

A native of South Australia's Barossa Valley, Schroeder makes wine by subtle stylistic methods that he picked up back home, and he finds it fascinating to compare his ports—one, a tawny made from Zinfandel and Shiraz, the other, a Shiraz ruby—to those of other regions.

"It's not to be critical or to try and make them the same, but just to understand the differences between the regions," he explains. "That's what makes wine so interesting to so many people. We definitely don't want to emulate Portuguese port, but we certainly can incorporate some tried and true techniques and possibly modify them to fit our own climate and conditions."

Dixie Gill, director of marketing and communications for Premium Port Wine, attributes some of the characteristics of true Porto to the production methods: when the brandy is added; the proof of the brandy, which may range from 140 to 200; and, perhaps most importantly, the pressing of the grapes, which still involves bare feet in parts of the Douro Valley. But grape-stomping is no longer the esteemed career that it once was, and the Symington family, a leading Porto producer in Porto, has invented a machine that mimics the work of the human foot. The mechanism presses the grapes for hours, and a set of silicon toes does the crushing. Like the pads of the human foot, the silicon does not break the seeds of the grapes, which contain bitter tannins.

Producers in Portugal are pushing the E.U. to tighten restrictions on outsiders calling port "port," and this bugs Peter Prager of Prager Winery. "Porto is a place on a map, but you can't show me 'port' on a map. It's not a place. It's a word and a style of wine, and we make it in California."

Quady may have struck gold with the name Starboard, but, he concedes, it's just a name.

"Whether it's sparkling wine or Rhone style, people in California need to start thinking about what the wine we make is and stop comparing it to places in Europe," he says smartly. "Life is too short to spend it bickering about terms and names."

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|