home | north bay bohemian index | music & nightlife | band review

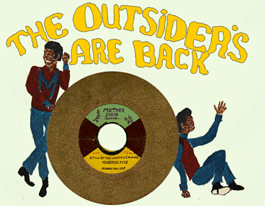

Faux Audio: Cardboard cutouts stand in for vinyl in the private oeuvre of Mingering Mike.

Essay: Mingering Mike and Beirut

Two oddball artists draw inspiration from copious amounts of time spent alone.

By Sara Bir

The most striking music story of the year, the one that's inspired thousands of blog posts and indie press odes, is the tale of a musician who has not released a single note of recorded music. He's never performed live, either, because he does not exist.

The tale of Mingering Mike broke several years ago, when a crate-digger named Dori Hadar stumbled across a treasure trove in a Washington, D.C., flea market. While flipping through old records, he came across an unusual hand-painted cardboard sleeve for The Mingering Mike Show—Live from the Howard Theater. It contained not a vinyl LP but a cardboard stand-in with a homemade label glued on. Hadar searched further, finding dozens more of these curious nonreleases. He bought them all and, both puzzled and beguiled, posted pictures of some on the forum Soulstrut.com.

The pretend records struck a chord with readers, and Hadar set out to find the real man behind this Mingering Mike fellow. After a decent amount of private detective–style legwork, he located a meek but guarded middle-aged man: the real Mike.

The book Mingering Mike: The Amazing Career of an Imaginary Soul Superstar (Princeton Architectural Press; $24.95), which came out this summer, ties together the loose ends for people who heard about Mingering Mike on the radio or read about him in the New York Times. It contains images of Mike's records—hundreds of them—that create a testament to the soothing power of private fantasies and the depth of seemingly ridiculous, unattainable dreams.

The appeal of the Mingering Mike saga is its odd mix of familiarity and futility. How many of us doodled logos for our own imaginary bands on notebook covers or sang off-key songs a cappella into a tape recorder? But most of us stopped at that. The astounding thing about Mingering Mike's vaporous enterprise is the scope of it. Flipping through the LPs and singles and album gatefolds in the book, you realize what a delicious escape Mike created for himself, an empire of music so elaborate that no amount of actual songwriting and recording could match its perfection.

Mingering Mike is heartbreaking in a way, because even though its artwork and faded black-and-white snapshots of the real Mike are captivating, a reader can never fully get inside them; it's a constructed world too sprawling for an outsider to feel fully comfortable visiting, because he didn't craft it with the intention of sharing it with the outside world. If Mike really wanted to be the superstar Mingering Mike, he'd have pursued an actual musical career, which has many pitfalls and few breaks. In his fantasy, Mike had total control.

Actual music starts out in the same way, though—in an artist's cloistered headspace. And with many iconoclastic songwriters, the coziness and intimacy of creating music alone in a bedroom or basement will always be part of their image. Zach Condon is one such fellow.

Condon performs as Beirut with a shifting ensemble of musicians, eschewing the standard drums-bass-guitar setup for accordion, glockenspiel, strings and horns. By the time he dropped out of high school at age 16, he'd already recorded reams of songs in his bedroom, where he also recorded the majority of last year's Balkan-happy Gulag Orkestar, which charmed the NPR and indie-music blog set. That he was only 19 at the time simply added another layer of color to the package.

Condon has lightened up the Gypsy fetish of Gulag Orkestar, and on Beirut's new album, The Flying Club Cup, moved on to the France of cafes, chain-smoking, berets and baguettes. Condon's use of melancholy horn arrangements in particular reflects an affection for the consummate French pop storyteller, Jacques Brel. Unlike Brel, whose keen lyrics could prompt tears and laughter in the same verse, Condon prefers to emote not in words, but in a warble recalling another neo-vaudevillian, Tiny Tim, albeit with the falsetto unplugged. It's Beirut's best asset and worst enemy, sometimes sweet and sometimes cloying.

Beirut isn't about authenticity, but rather cherry-picking certain elements to establish a nostalgic sound-picture of the Europe that exists solely in the minds of overimaginative Americans. Condon has spent time in France, but The Flying Club Cup is more about the idea of France.

And perhaps Beirut is not about Condon, and Mingering not about Mike, but our idea of an artist: precocious, na´ve and dreaming big in the bedroom.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|