home | north bay bohemian index | news | north bay | news article

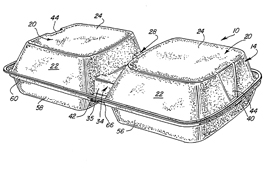

EVEN BAD DESIGN IS DESIGNED: Those hateful clamshell packages and other impossible-to-breach plastic containers have their own patent process.

Shell Shock

Theft-proof plastic packaging isn't just irritating; it's bad for your health and the planet

By Jessica Lussenhop

Many viewers found themselves howling in agreement with Larry David during a recent episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm. After two minutes of attacking a hermetically sealed plastic package with a butter knife, a screwdriver and a chef's knife, he—and many of us—wanted to know: "Why would you manufacture a product you can't open?"

Why indeed? And by far the worst part is that the damned things, often called "clamshells," are sharp, and a slip of the hand can result at the very least in the equivalent of a paper cut on steroids—and at the very worst a trip to the emergency room.

There's actually a term for this phenomenon. It's called "wrap rage." Think about it. Uncle Frank has had a couple of eggnogs by the time Little Sally comes running with her new Bratz doll, all hopped up on sugar and gift-opening adrenaline. She shrieks when her doll is still sealed in the plastic tomb five minutes later, and an agitated and tipsy Uncle Frank goes for the sharpest knife in the drawer. It's a recipe for disaster.

Emergency room physician Dr. Greg Whitley agrees. "I've definitely seen lacerations from opening clear plastic containers. Most of the injuries involve opening the containers with a knife, and people cutting themselves with the knife or with the sharp edge of the plastic," he says. "These injuries can involve tendons and nerves in the hand, so they can be quite serious."

In the last few years, something like 6,000 wrap ragers hurt themselves badly enough to get those ambulance bells jing-a-linging all to the emergency room, according to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission.

That's not the only problem. As the nation becomes increasingly concerned with going green, the seemingly indestructible cases are easily imagined whiling away the centuries in a landfill or beefing up the Pacific Ocean plastic gyre. This is not news to the packaging industry. One source in package manufacturing contacted for this article would not even talk about them, "because people hate them," she said.

"Everybody complains about these things constantly," says Dr. Fritz Yambrach, associate professor of packaging in the Applied Sciences and Arts Department at San Jose State University. "Here's the deal—it's on items that can be pilfered pretty easily. Anything people will steal and jam down their pants."

The reason clamshells are impossible to open is because they're supposed to be impossible to open. According to Yambrach, the plastic is made mostly from pellets of polyethylene terephthalate and extruded out into sheets before being molded into shape and diffusion-bonded, or heat-sealed, closed. Your puny weapons are no match against industrial-strength heat sealing.

About a year ago it was all the rage for companies to badmouth the clamshell. Sony even launched something it called the "Death to the Clamshell" campaign. But one year later, you'll probably still be able to find many of their products heat-sealed out of reach. "We're certainly cognizant of the environmental health aspects involved in packaging," says David Migdal, VP of public relations at Sony. "The rub here is, how do we effectively display some of our smaller products and keep them safe from thieves at the same time?"

There is some good news. Yambrach says the industry has steered away from making the shells out of polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which is believed by some to release cancer-linked chemicals. And some businesses are moving more aggressively toward a clamshell-free future, like Amazon.com, which launched its "Frustration-Free Packaging" initiative last year with 19 products available to be shipped in a simple cardboard box. This year, the count is up to 30 manufacturers and 350 products available frustration-free. "Wrap rage is real," wrote Amazon.com spokesperson Anya Waring in an email. "Customers have been responding very positively to the program."

Amazon, however, has the benefit of being an online business, and manufacturers say they're boxed in by the simultaneous need to draw customers in and shut thieves out.

One solution, says Assemblyman Bill Monning, in the spirit styrofoam and plastic bag bans, is political. "Extend producer responsibility," he says. "Maybe they're going to have to pay through fees that anticipate the cost of recycling and recovery. What's the real cost of that package in terms of climate change, in terms of danger to the environment, the danger to the consumer? Does that victim of the cut—do they have health insurance?"

Health insurance, climate change—one puny package can touch on some of the most crucial challenges facing our country. But that's the power of the clamshell. We have long wondered whether our creations would one day turn on us. We need only look beneath the tree in all those pretty packages to see evidence that it's happened. Consider yourselves warned this holiday season, before all shells break loose.

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|