home | north bay bohemian index | features | north bay | feature story

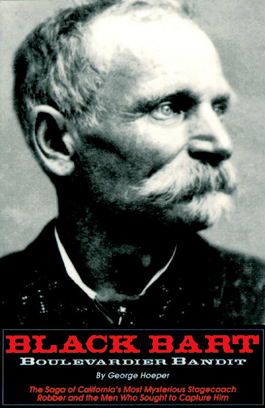

P08 Considered a 'gentleman' bandit, Black Bart killed no one and refused to take personal belongings during his heists, perferring to liberate Wells Fargo's band boxes. Last year, Cloverdale divested itself of Black Bart's name for its annual arts festival, preferring not to be associated with a celebrated criminal.

Legend and Lore

Black Bart made a name for himself in Sonoma County—one that Cloverdale now rejects

By Isaac Levinson

T hrough the wild forests and coastal plains of western Sonoma County on Aug. 3, 1877, a Wells Fargo stagecoach traveled cautiously along the beaten trail between Point Arena and Duncans Mills. After a rigorous 13-hour journey, the coach and its seven passengers eagerly anticipated their arrival into Duncans Mills. As the coach bumped and jarred along the redwood forest trail snaking close to the Russian River, a bandit with a flour sack covering his head burst out from behind a rock and pointed his shotgun directly at the coach driver.

"Stop!" The bandit yelled as he adjusted the makeshift mask covering his face, revealing only intense blue eyes underneath the dull and faded flour sack. The driver, tired and unarmed, obeyed the outlaw and brought the stagecoach to a sudden stop. "Please, throw down the box," the bandit politely but firmly commanded, keeping his shotgun pointed at the coach driver.

After giving the mailbag and the Wells Fargo box to the blue-eyed bandit, the coach started back down the forest path as the bandit courteously tipped his hat to the passengers inside. Within minutes, the outlaw disappeared into the towering redwood forest. When the authorities arrived hours later, they found only a poem:

"I've labored long and hard for bread, For honor and for riches, But on my corns too long you've tred You fine-haired sons of bitches." —Black Bart, the PO8

A few days after the holdup, Charles E. Bolton, well-dressed and impeccably mannered, strolled along the hilly, cosmopolitan boulevards of San Francisco. An avid theatergoer and a frequent guest of San Francisco's most prestigious homes and restaurants, Bolton lived the good life hobnobbing among San Francisco's elite, befriending business magnates and high-level city and police officials.

Known as a successful mining engineer, Bolton would frequently leave the city and head off toward the wilderness to conduct "business." Only later would San Francisco's high society find out that, rather than mining, Bolton (whose real name was Charles E. Boles) lived a double life robbing Wells Fargo stagecoaches all across Northern California under the alias Black Bart.

Until he was finally captured in 1883, Black Bart, "the gentleman bandit," had robbed 28 Wells Fargo stagecoaches using only an unloaded shotgun. And while accomplishing his record number of holdups, the most by a single person in Wild West history, he did so without robbing the passengers or killing anyone, a feat he was outspokenly proud of even as he entered the walls of San Quentin.

Yet Black Bart was only one of many who succumbed to a life of crime along California's fresh frontier trails. Author and historian William B. Secrest explains: "For some people, depending on your psychological makeup, it wouldn't take much to push you into a life of crime, especially in a frontier area with a lot of open spaces. You get the idea that you can do something and get away with it, so you try it once or twice. After three or four times, you get the feeling that you'll never be caught." That's probably when Bart started to become overconfident. "By the time he held up four or five stagecoaches, Black Bart probably developed a smart-alecky attitude. That's when he left that poem."

Perhaps Black Bart deserved such an ego boost with such a stunning record. "When you stick up 28 stagecoaches and don't get caught, you're pretty doggone good," Secrest says. "And I don't know of any other stagecoach robber in the West that did that."

What also differentiates Black Bart from other early California outlaws was his unorthodox decision not to use a horse or work with accomplices. This lone bandit was able to elude authorities for so long in part because investigating detectives could not believe that one man could travel such vast distances in so little time. Instead of looking for a single person, they questioned outlaw gangs believing that two or more bandits must have been involved.

Yes, the urbane bowler-hat-sporting Charles Bolton who ambled about the streets of San Francisco was also a longtime miner and Civil War veteran who had, over the years, become a marathoner of the forest and fields, hiking through unsettled wilderness at amazing speed, regularly covering 20 miles of roiling land a day. When traveling through more settled and populated areas, Bart dressed and acted like a gentleman, allowing him to move inconspicuously along Northern California's growing transportation network of railroads and ferries.

After serving four years of a six-year sentence in San Quentin, his time was reduced for good behavior, and Black Bart mysteriously disappeared. While he was not documented in public records thereafter, traces of him can still be found in Sonoma County today.

Near the site where he left his poem, the Blue Heron Restaurant in Duncans Mills commemorates Bart with an inscribed bronze plaque. The plaque, which was created in 1989, immortalizes Bart's poem and gives some information about the outlaw "poet." Although he was no Robert Frost, his rhyming poem often gets a chuckle from regulars and out-of-towners alike.

Yet Black Bart's most controversial remembrance seems to have been left in Cloverdale—in the form of a festival. After running each spring for 15 years, the Black Bart Festival was changed to the Boulevard of the Arts Festival last May to create a fresh, arts-oriented event meant to draw in new elements of Cloverdale's growing community.

Instead, the festival transformation formed a rift in the town over Black Bart's questionable reputation and place in the community. Cloverdale resident Susan Nurse says, "In Cloverdale, Black Bart's a political hot potato. There is a myth that he was a Robin Hood—he took from the rich but he gave to the poor. That's simply not the case. We have other things more positive in Cloverdale's past that we could be focusing on, and we're not."

And she poses a compelling question. "By celebrating an outlaw like Black Bart, are we somehow admiring this get-rich-quick, easy kind of lifestyle?"

Bonnie Asien, executive director of the Cloverdale Historical Society, seems to disagree. "I don't think anyone would hold Black Bart up as an example to show, 'This is how you beat the system,'" she says. "The original celebration was just about family fun. A good old-fashioned street party with a cow-chip toss, bathtub races and a square-dance party."

Asien stresses that it's more about the era. "Cloverdale did start out as a stagecoach stop, and it does have a Western heritage. It's about celebrating that."

While it's unclear whether Black Bart would have approved of associating his name with tossing dried circles of cow manure, it is evident that the controversy is not about Black Bart the man, but rather the legend. Dorothy Marder, a museum docent for the Cloverdale Historical Society, says, "He took on the persona of the novella character 'Black Bart,' so with his image, more of it is legend than reality. For most people, it's almost as if he wasn't a real person. They're not thinking about the real Black Bart during the festival."

Marder shakes her head, "Every once in while people try to get rid of Black Bart, but he always comes back. It's happened many times, but he always comes back."

Right before his disappearance, Black Bart strolled out of the gates of San Quentin and was immediately surrounded by reporters asking if he would return to a life of crime. He replied with a staunch "No." When a local Chronicle reporter asked him if he would continue to write poetry, he retorted, "Young man, didn't you just hear me say I would commit no more crimes?"

It seems that Black Bart had the last laugh.

"Here I lay me down to sleep

To wait the coming morrow,

Perhaps success, perhaps defeat,

And everlasting sorrow.

Let come what will I'll try it on,

My condition can't be worse;

And if there's money in that box

'Tis munny in my purse."

—Black Bart, the PO8

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|