A MOVIE-LOVING thief named Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) has just helped himself to a vehicle belonging to some American servicemen. On the way home, he shoots a cop.

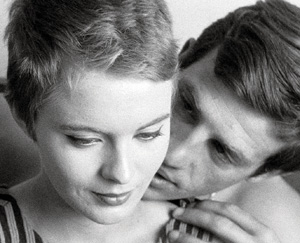

When he gets to Paris, he picks up an acquaintance, an amoral, passive American girl named Patricia (Jean Seberg) who has come to Europe to marinate in the culture. Michel thinks he sees a reflection in himself in this crop-haired blonde, someone as free as he is. But she knows how to look out for herself, and Michel figures her as a coward, who won’t join his crime spree.

Fifty years on, Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless is the kind of breakthrough cinema that’s positively viral; it makes you wish they sold movie cameras in the lobby. It was stolen off the sidewalks by ex-journalist-turned-cinematographer Raoul Coutard and cobbled together for $90,000.

The revival makes it easy to see why Breathless was the breakthrough hit of the French New Wave. It is a simple, accessible movie of adventure and romantic stalemate. The restored version, overseen by Coutard, seems faster than ever, and it must be because you can see so deep into the horizons that Michel, the clever/dumb, beautiful/homely mec, is aiming for. If you ever longed to walk into the frame before, this restoration gives you more leg room. There’s a new shine to the captured moment of streetlights flickering on the street, a fresh gleam to the silvery, diabolically cool surfaces of Seberg (whose resistance to Michel, given the outlandish ambient sexism everywhere around her, makes much more sense now than it did in 1960). The argot is cleared up in the new subtitles, even if the end of Michel’s straight-to-the-camera pronouncement about the glory of France (which could be lifted word for word for California) probably ought to have ended with a bit more profanity.

The jump cut, which made the invisible art of editing deliberately visible, was maybe the most shocking thing about Breathless, though this trick quickly became essential to the vocabulary of 1960s film. Richard Raskin’s intrepid article “Five Explanations for the Jump Cuts in Breathless” discusses the lingering controversy about Godard’s reasons, including: (1.) deliberate sabotage, (2.) a last-ditch attempt to save a purportedly mediocre film by ruthless cutting, (3.) an innovation to dazzle us novelty-loving, easily bullshitted critics. The list actually goes on past five: an homage to cubism; a summing up of the disassociated moral state of the predatory Michel; a way of creating syncopated visuals that match the jazz on the soundtrack, another innovation; and an attempt to make Breathless just as Hitchcock said a film ought to be: life with the boring parts cut out.

Just as it broke the boundaries of what was being done with character and visuals, Breathless mated the hard-boiled guilt of cheap gangster films with a few French intellectual traditions: the lust for encyclopedic definition of states of being and mind, the crafting of aphorisms, and the urge to control emotion: “Be reasonable,” is what a French mother tells her bawling toddler.

So it’s a strangely international film: Belmondo’s tenderest moment comes as he regards a photograph of Humphrey Bogart. Jean Gabin, France’s Bogart, would have felt just as at home in this plot of a criminal undone by love for an elusive, chic little sphinx.

In the midst of a summer of event movies meant to be crowded into and forgotten by next weekend, this revival is a real event. (Happy to see that Jim McBride’s ill-starred but reportedly worthwhile 1983 remake will be revived by Stanford’s Eliot Lavine at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco.)

Pauline Kael’s take, “A frightening little chase comedy with no big speeches and no pretensions,” sounds like a dis, but it isn’t. The cinema industry, which prided itself on important lessons and sympathetic characters, got faced down in Breathless; cinema had to make room for irrationalists, impulsivists and beautiful losers.

The existential abyss hasn’t shrunk in the last 50 years. Decades of calm killers and amoral molls—in the movies and outside of them—have taken away the frightening part Kael wondered at. We live in a now-familiar world that Godard helped create. Despite that familiarity, the film is a constant surprise, suffused by the freshness of a director of shattering talent, making a movie with confidence and wit.

Breathless

1960; unrated; 90 min.

Opens Friday at CinéArts Santana Row, San Jose