While researching Latino portraiture from the 1800s, the photographer Ken Gonzales-Day found an image of a young Latino man. “Last man hanged in Los Angeles,” was written on the back.

When he read that phrase, Gonzales-Day came to the conclusion that he didn’t have a clear understanding of California history. To make sense of his discovery, he began to work on the series of photographs that’s now known as “Erased Lynching” (2006). The Santa Clara University Art Department’s exhibit “Ken Gonzales-Day” features several of his photographs from the collection.

In “Hanging Trees: The Untold Story of Lynching in California,” an episode of the KCET program Lost L.A., the filmmakers interview Gonzales-Day and author Jared Farmer. Farmer’s book Trees in Paradise: A California History is a field guide to trees from a historian’s point of view. He provides the missing context for the photographer’s discovery. “The victims of lynching were disproportionately Mexican American and Chinese American,” Farmer explains to the camera. “And the lynching rate for Mexican Americans in this time period was roughly equivalent to that of African Americans during the period of Jim Crow.”

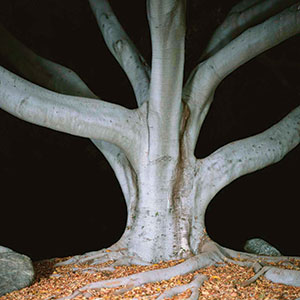

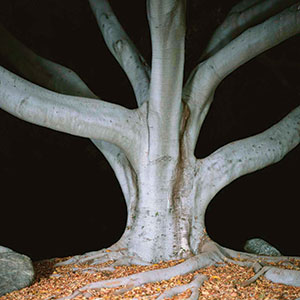

Armed with this information, Gonzales-Day decided to make the story of these lynchings visible. The photographs approach the subject in a couple of distinctly different ways. In images like Nightfall I, Holcomb Hangtree and Now he swings from a tree, two doors down from where I write, Gonzales-Day focuses only on the trees themselves. Holcomb Hangtree and Now he swings from a tree appear to be daytime shots of any rural California landscape. The angles are straightforward and well-composed. But it’s impossible to think of them as innocuous, bucolic scenes of nature in this context. If these trees could speak, they’d have terrible stories to tell.

Of the three images, Nightfall I is the most striking. He crops the elongated limbs so that the ends are cut off. If there are any leaves left on this centuries-old tree, we don’t see them. It’s also set against a background of pure blackness on the darkest of winter nights. The light cast against the trunk makes the tree’s bark look like it’s made of sinuous human flesh and bone. Even without knowing what the artist is referencing, he succeeds at evoking an ominous atmosphere.

Gonzales-Day doesn’t include any lynched bodies in his imagery because, he says, “Trying to tell a story without exploiting or victimizing the person you’re telling the story about is a common challenge for photographers in general. … I didn’t want it to be about re-victimizing the bodies.” Instead, he redirects the viewers’ attention so that they’ll consider the people in these circumstances “who would allow these things to happen.”

Those people appear in Marietta, GA (Leo Frank) and The unsolved case of ‘Spanish Charlie.’ In Marietta, GA, a group of white men gather around a massive tree. One man stands with his arms folded as he glares directly at the camera. It’s a sepia-toned image from 1915 that Gonzales-Day has altered. The psychic aftermath of despair remains in the frame even though he’s removed the hanging body from the scene of the crime. It’s an effective strategy. We look into the angry man’s eyes, studying his and the other men’s button-down shirts, belts and hats. They seem like ordinary guys who’re hanging out together for a weekend hunting party, casually standing around after they’ve lynched a man. They represent “the banality of evil” that Hannah Arendt once wrote about, but in this case, an evil that’s uniquely American.

‘Spanish Charlie’ is a chromogenic print from 2015. It’s a companion piece to the artist’s Run Up, an impressionistic short film “inspired by California’s last documented lynching of a Latino.” The well-dressed men and women look like their 1915 counterparts from Marietta, GA. But Gonzales-Day adds in two women of color at the far edge of his frame. They suggest the presence of witnesses, or the artist’s proxies, who will not forget what’s happening that day. “Erasing Latinos from history,” Gonzales-Day says, “polarizes race to black and white in the United States.” With this collection of photographs, he’s adding Latinx stories, ones that have been ignored or omitted, back into the history books.

Ken Gonzales-Day

Thru Jan. 24

Santa Clara University, Edward M. Dowd

Art and Art History Building Gallery