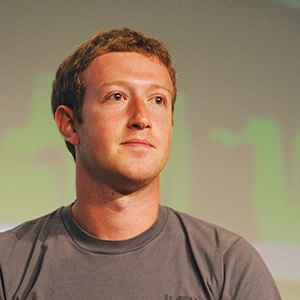

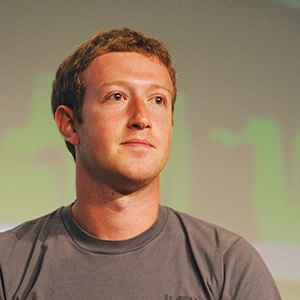

Noiselessly, Zuck padded into the conference room, staring at his smartphone, and sat down. Now the meeting could really begin.

Sheryl Sandberg kicked things off. “Mark, as you know we’ve been considering some new initiatives in Ads.”

Way to understate things, Sheryl.

The company had announced its intention to go public months ago, and the IPO was imminent. Precisely when the company was opening itself to investor scrutiny, its revenue growth was slowing, and revenue itself was plateauing. The narratives the company had woven about the new magic of social media marketing were in deep reruns with advertisers, many of whom were beginning to openly question the fortunes they had spent on Facebook thus far, often with little to show for it. A colossal yearlong bet the company had made on a product called Open Graph, and its accompanying monetization spin-off, Sponsored Stories, had been an absolute failure. The company’s senior leadership had called on the Ads team to dream up something fast to revive the lagging fortunes of the enterprise. This being Facebook, the initiatives originated not at the senior levels of the company but rather at the lower: random engineers who had conceived of a bit of cleverness, glib product managers who had managed to seduce a few people to their vision.

I knew a thing or two about the value of Facebook data. A year before, I had been hired as Facebook’s first product manager for ads targeting, charged with converting Facebook’s user data into money by whatever legal means available. This task had proved considerably more difficult than it sounds. For months, the targeting team and I had been testing and ingesting every piece of Facebook user data—posts, check-ins, shared links, friends, Likes—to see if it would improve the targeting and delivery of Facebook ads.

Almost without exception, none of it increased monetization to a substantial degree.

The miserable conclusion was that Facebook, though assumed to be a rich repository of user data, did not in fact have much commercially useful data at all.

The second and third proposals were more radical from a business, if not a legal, perspective and reflected this grim realization. The plan was to join the Facebook Ads experience to data generated completely outside Facebook. Thus far, all ads on Facebook used FB-only data, but this proposal would involve tapping into “external” data like browsing history, online shopping and offline purchases in physical shops. Historically, Facebook had been a walled garden, in which advertisers could not use their data on Facebook or use Facebook data elsewhere. From the data perspective, it was as if Facebook was absent from the Internet ecosystem, off on some island under its own complete control. Via two different technical mechanisms—one roughly in keeping with the existing Ads system, another vastly more sophisticated—we were proposing to bridge that divide at last.

The popularity of Facebook’s Like and Share buttons meant Facebook was on something like half the Web in a mature market like the United States. As you browse the Web far and wide, from shoe shopping on zappos.com to news reading on nytimes.com, Facebook sees you everywhere, as if it had a closed-circuit TV on all city streets. Facebook’s terms of service had so far prohibited the use of the resulting data for commercial purposes, but this bold proposal suggested lifting that self-imposed restriction. As ominous and powerful as that may sound, it was not guaranteed to succeed, as the actual value of that data was unknown.

Zuck and Sheryl hated projecting PowerPoint decks, so somebody had printed out the slides I had prepared and stapled them into neat packets. Brian Boland had summarized debates and meetings going back months in easy-to-parse bullet points on the first page.

That’s all anyone ever saw. My detailed technical schematics, with walk-throughs of data flows and outside integration points, were, as I suspected, completely ignored. Sheryl wouldn’t have cared about the technical detail, and Zuck wouldn’t have had the patience to go through it anyhow. As I observed more than once at Facebook, and as I imagine is the case in all organizations from business to government, high-level decisions that affected thousands of people and billions in revenue would be made on gut feel, the residue of whatever historical politics were in play, and the ability to cater persuasive messages to people either busy, impatient or uninterested (or all three).

If ads already made Zuck drowse, then privacy trade-offs would have sent him keeling over off his Aeron chair. Whatever Zuck approved, we’d engineer the legal workings.

“So do we think using the plugin data will make us more money?” Zuck asked.

My brain reacted like an old truck in winter, failing to start and cranking away futilely.

“Well, that depends . . . I mean, there are lots of things that affect monetization. We haven’t really done the controlled A/B studies, as it’s legally touchy, but it is possible that it’s unique data in some way. Of course, there’s also the issue of whether the Like button is even where we want it to be datawise, as—”

“Why don’t you just answer the question?” blurted Zuck, cutting me off.

Panic breeds focus.

“I don’t think it would move the needle much, given recent experience,” I replied flatly. Silence, as we all waited for what Zuck would say.

“You can do this, but don’t use the Like button,” he said finally. The statement percolated through the room.

“So yes to retargeting, but no to using social plugins,” reiterated Sheryl, more question to Zuck than assertion.

“Yes.”

And that’s all he ever said about the matter.

I was giddy inside. The last two months of scheming had worked out. We could build this magic targeting device I had proposed that would combine the two great Internet data streams, Facebook and the outside world, and change everything.

This edited excerpt was published with permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

C2SV

Friday, Oct. 7 11:15am

Speaker session and book signing

Chaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon Valley