On the vibrant campus of Santa Clara University is the de Saisset Museum, a beacon of cultural exploration that offers inclusive exhibitions and educational programming that resonates with both art lovers and scholars.

This year marks de Saisset Museum’s 70th anniversary—a fortuitous time to find out more about the ideas of Dr. Ciara Ennis, the still relatively new museum director. Prior to her tenure at de Saisset, Ennis built the program at Pitzer College Art Galleries in Claremont.

“I love working in academic environments because you can do really exciting programming and you don’t have to worry about making sure your program is acceptable to huge amounts of people. You can be more risky in terms of what you do,” Dr. Ennis says. “It’s a space for experimentation.”

The museum today is a testament of the work of former de Saisset director Lydia Modi-Vitale, who shaped the museum’s vision and experimental legacy in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Now, drawing inspiration from Modi-Vitale’s innovative spirit, Dr. Ennis aims to revitalize the concept of a “Museum in Progress” at the de Saisset. “There were a number of new initiatives that I started, one being the cycle of contemporary research-based exhibitions,” Ennis says, “and that really is looking at artists whose exhibitions expand way beyond the art world.”

Her previous curatory museum work in Southern California and her academic journey, which culminated in a Ph.D., explored “16th and 17th century museums as a model for rethinking contemporary curation, or contemporary curatorial practice.”

Her approach transcends conventional museum structures by fostering interdisciplinary connections while embracing “transhistorical dialogues.”

“The ‘Museum of Progress’ is based on the idea that unlike traditional museums, which are slow to change—as we know, museums really do need to change in terms of their elitist and classist molds, they need to be more inclusive—the ‘Museum of Progress’ is all about fluidity, and being open to respond to new ideas and change,” Ennis says.

As for she means by an “interdisciplinary transhistorical model,” Ennis explains that works in the permanent collection—whether they’re from the 17th or 18th century, or other eras—are presented in conversation with contemporary shows and programming.

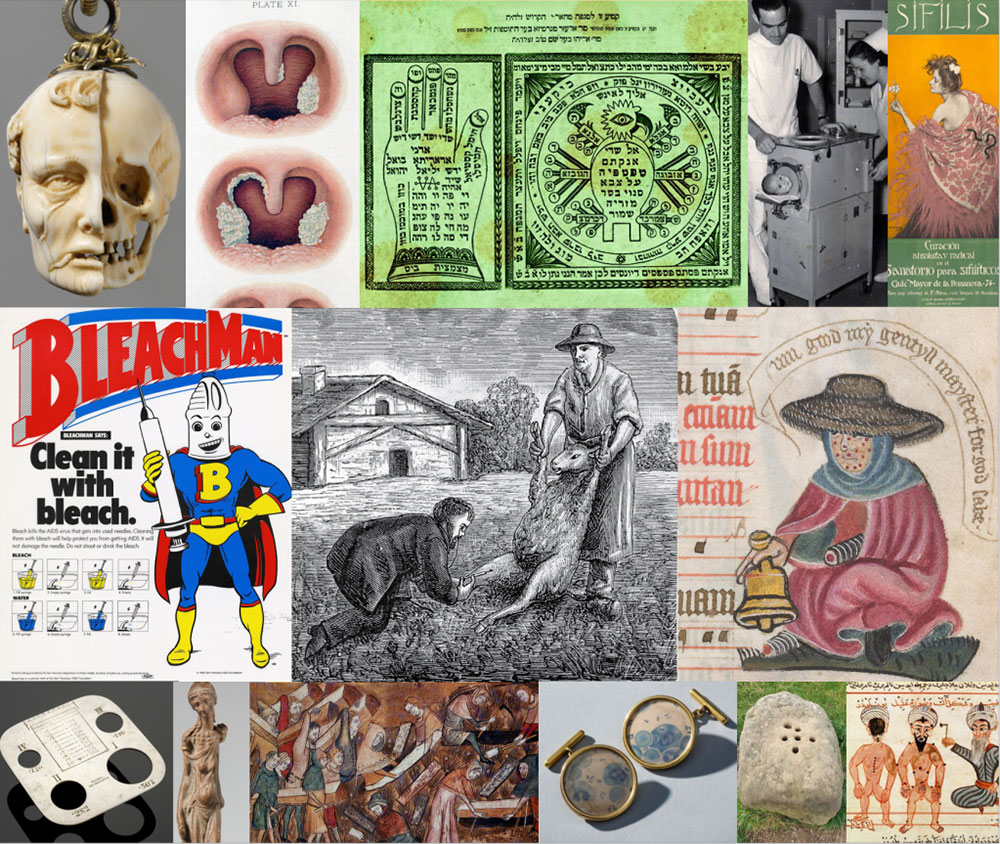

The upcoming contemporary exhibition—“The Plague Archives,” by Maya Gurantz—exemplifies this new approach. Spanning centuries and continents, the new installation delves into the cultural and social perceptions of plague, inviting visitors to contemplate historical amnesia and collective memory loss.

“Maya Gurantz’s show takes a closer look at the history of plague and how we define plague—both socially, culturally and otherwise,” Ennis says. “So, this looks at it from a huge historical lens—from the twelfth century to present day. I’m really excited about artists, like Maya Gurantz, who have research-based practices and whose projects expand beyond the museum because I am always searching for ways to provide access to non-art people,” she says. “I feel sometimes the art world is very myopic in its thinking.”

Just as important, however, is that ideas are “multilayered, interdisciplinary, and visually very exciting. You could have the most interesting ideas in the world, but if they are not presented in a visually exciting or seductive manner, you’ve lost everyone. So, the artists that I tend to work with have a very exciting visual language.”

Ennis’ vision for the future of de Saisset emphasizes the potential of academic environments in nurturing experimental programming. Universities provide a fertile ground for bold ideas and interdisciplinary collaborations, she explains. Leveraging the expertise of faculty and staff across disciplines, the museum enriches its programming with diverse perspectives and its expansive permanent collection.

An ongoing permanent exhibition, “California Stories from Thámien to Santa Clara,” is a testament to reexamining historical narratives in collaboration with Indigenous communities. Continuously revised to address historical erasure, this exhibition underscores the museum’s commitment to inclusivity and historical accuracy.

Her vision extends beyond the walls of the museum, though the director emphasizes the potential of an academic environment like de Saisset for nurturing experimental programming like the Wunderkammer model. The basis of her dissertation, the Wunderkammer is the “cabinets of curiosities” on which early museums were based.

Ennis argues that Wunderkammers, maligned as trivial or non-serious, “were incredibly progressive in how they were organized, and structured in the sense that they put together different subjects from different disciplines and historical eras, and as a result of that, they inspired new associations and new ideas.”

This is largely what her research was about, she says, and now she aims to materialize this experimental model to some degree. “After I finished my dissertation in 2018, one of my goals was to think about how radical Wunderkammers were and how they have been misrepresented historically.” I think it’s important to break down traditional hierarchies. If we look at collections hierarchically, we think about how decorative objects are viewed further down the scale than, say, paintings and sculptures, which are at the top. All of this is being changed or challenged” with Wunderkammers.

Wunderkammers act “in contrast to more traditional museums” that have one collection classified in rigid ways, Ennis says. “It’s about opening up those classifications and seeing how we can make them more expansive and put them in dialogue in a way that creates more ideas, rather than shutting them down.”

Ennis’ proposed initiatives for the development of the de Saisset represent a paradigm shift in museology. “I hope this is a lasting movement,” she asserts. “Something has to break this very rigid museological model.”