A little after 2pm on Oct. 10, 1982, Bill Graham took to the stage at Stanford’s Frost Amphitheater. Standing before nearly 10,000 people, the legendary Bay Area music promoter had a few housekeeping items to address.

“They never used to let anyone right in the front,” Graham can be heard saying on a recording of the night. “But you’re a different species, and we’ve convinced them that you can take care of the steps here. Be careful as you’re boogieing about.”

The second item:

“Over the years we’ve had problems here of people climbing up the trees,” he says, before adding, diplomatically, “We don’t want any accidents.

“The Haight Ashbury Clinic is in the corner there. Watch what you eat, watch what you drink, have a good time.”

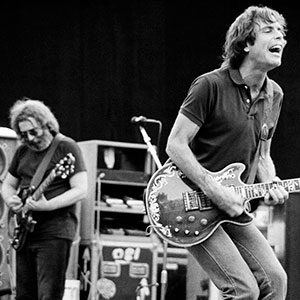

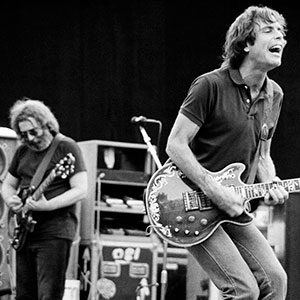

Within a minute of leaving the stage, Bay Area music history happened. The Grateful Dead played for roughly four hours that day, capping their first residency at Frost.

Diehard fans consider that day’s set their strongest of the decade. Nearly three hours into the music, the sun set over the dense canopy of oaks, bays, sycamores and spruces, and the band played on.

Throughout the ’80s, the Dead would play another 12 shows at Frost. Though the Deadicated consider these shows among some of the band’s most legendaryand while the Frost bootleg tapes are some of the most popular in the band’s sprawling canon of live setsit’s clear that Stanford administrators had differing opinions. After the Dead’s final set in 1989, Stanford let the amphitheater lapse into a dormant state for almost 30 years.

The Frost Amphitheater reopened in May, finally becoming the full-fledged venue it was always prepared to be. True to history, Grateful Dead tribute band Joe Russo’s Almost Dead is even playing one of the inaugural concerts.

But there’s a catch. Goldenvoice, the production company responsible for booking Frost’s pop music eventshas been accused of anti-competitive practices by industry insiders and has drawn criticism over its owner’s political affiliations.

LONG STRANGE TRIP

Highlighting a series of new sites on campus, the 1937 volume of Stanford Quad, Stanford’s yearbook, describes the Frost Amphitheater.

“Behind the theater is the new amphitheater, which can use the facilities of the theater for productions in the open air,” it states. “Though the class of 1937 will graduate in it, the planting and growth of trees will not be completed for 50 years.”

Officially opened on Jun. 13, 1937, the Frost Amphitheater covers 20 acres and rises more than 50 vertical feet from the stage to the back row. Designed by landscape architect Leslie Kiler, construction of the Frost included the shipment of more than 500 trees, all of which were interwoven around the venue’s perimeter, creating the feel of a dense forest, a likely influence for Graham’s tree plantings at Shoreline Amphitheatre.

Plans had already begun back in 1909. But in the 20th Century’s early years, Stanford, like many universities, experienced money problems. The first World War hit, quickly followed by the Great Depression. Then, in 1932, the school lost out on almost $3.25 million in matching donations from the Rockefeller Foundation.

Stanford always had a conservative bent and was deeply skeptical of taking a government handout, but two years after losing the matching donation, Stanford had no choice but to accept funding from California’s State Emergency Relief Administration.

Throughout this period of turmoil, John Laurence Frost studied economics at the school. On track to graduate in 1935, he passed away due to complications from polio either shortly before or shortly after graduation (reports on this topic vary depending on the source). In order to honor their son, the Frosts donated $90,000 to the school (about $1.6 million today), for the purpose of dedicating a space “for the spiritual and cultural advancement of Stanford students.”

“The idea initially was to create another outdoor arts venue on campus,” says Stanford Live director Chris Lorway. “In the early years there was a whole series of university ensembles using the space.”

In the decades that followed, concerts were intermittent, often punctuated by heavyweights in jazz and R&B. In the middle of the century, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Ray Charles and Miles Davis played Frost.

During the ’60s, the amphitheater served as the venue for a small arts festival started by a faculty member. Shortly thereafter, Stanford decided to spread its arts program over the course of the year, and focus more on fine arts. It was this very decision that led to founding of Stanford Liveoriginally named Lively Arts.

Through the ’70s, events at Frost continued on an occasional basis. Then came the Dead.

“I think the university administration put a bit of a pause on things, because with the Grateful Dead came a certain culture that wasn’t necessarily aligned at the time with the mission and values of the university,” says Lorway.

That “certain culture” was, of course, what remained of the hippie movement: the dreamers, vagabonds, traveling merchants and psychonauts for whom the Dead were standard bearers. After realizing that shows attracted these audiences, Lorway says the school became extremely selective about their live actsto the point of inactivity.

“They kind of had a period of relative dormancy pretty much from ’87 until our reopening.”

THE DEAL GOES DOWN

Chris Lorway stepped in as executive director at Stanford Live in 2016. When plans to reopen Frost began, it quickly became clear that the operation would be too big to run in-house.

“We knew that in order to make our business model work, we were going to need to do some larger-scale shows in the space,” he says. Indeed, the venue boasts a number of big name acts this season, including Odesza (Jul. 17-18), Lionel Richie (Aug. 24) and The National (Sep. 1). “These days the only way to get access to top talent in the market is to work with a major promoter.”

In the area, there were already three major promoters at work: Live Nation, Goldenvoice and Another Planet Entertainment. In order to find the right promoter for their venue, Stanford Live put out a request for proposal.

“We invited all three of the majors to put together a proposal,” Lorway says. “And we had a committee that we had to put together, some Stanford staff and some external consultants. And we just came, at the end of that process, to find that Goldenvoice made the most sense for us.”

While Lorway describes the deal matter-of-factly, one candidate found the process questionable.

“It was a charade,” says Another Planet Entertainment founder Gregg Perloff. (Live Nation declined to comment for this story.)

Of the three promoters under consideration, Another Planet Entertainment (APE) is the only true local. Independently run since 2003, the promoter books venues in San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley and Tahoe. Normally adverse to interviews, Perloff decided to go on record for this story because of some particular concerns about the Stanford RFP process.

“In no way do I have any issue with Goldenvoice being awarded the contract,” he says repeatedly throughout our conversation. “My issue is with the process. It was a very flawed process.”

For Bay Area promoters, Frost occupies crucial territory. In terms of capacity, it sits between the Mountain Winery (2,500), and the Shoreline Amphitheatre (22,500). Geographically, it is to the north of both, making it a draw for both Peninsula suburbs and cities. It’s a bid any promoter would be excited to land. So when Perloff received the RFP, he went to work on his proposal. But, he says, there were red flags almost immediately.

“From day one, there were rumors that it was always going to go to Goldenvoice,” he says. “I don’t usually pay any attention to rumors, but those rumors were out there. We’re a very small industry, and people talk.”

In addition to rumors, Perloff says Stanford requested inordinate amounts of detail in proposals, but remained unavailable for questions.

“Usually when you are in the process of bidding for things, there is somebody who will speak to questions that you have,” he says. “But Chris Lorway was absolutely unavailable for any kind of questions, phone calls, etc. He made himself particularly unavailable. The only time that he became available was on the day of a walkthrough.”

One of the items Perloff wanted clarification on was an eyebrow-raising line in the RFP, a line that, in the 15 years of running Another Planet Entertainment, he had never seen before. It stated that “under no circumstances” were bidders to have any contact with Stanford employees during the bid process, “except in the context of Stanford-initiated discussions.” Perloff perceived this as a safety measure, protecting both parties against any chance someone would claim the deck had been stacked.

“It was kind of like, ‘Don’t try to leverage your relationships at Stanford; don’t try to talk to anybody,'” he says.

Despite rumors, a lack of communication and the concerning condition in the RFP, Perloff spent several months developing a proposal. Then, when showed up to deliver it to the panel, one of the decision makers, he alleges, slept through most of the presentation.

“I know I’m not going to win any points by saying that,” Perloff says, “but that’s what happened.”

At the end, Perloff learned Stanford had decided to partner with Goldenvoice over Another Planet. The reason: Another Planet already booked the Greek Theater in Berkeley and the Bill Graham Civic in San Francisco.

“Needless to say, I was quite upset,” Perloff says. “That wasn’t something they didn’t know about. Why did I bother to bid if they were just going to say to me, the reason that you didn’t get the bid was because of something they knew ahead of time? If they chose to go with AEG-Goldenvoice, then fine. They’re a private institution. But why the charade? Why the smokescreen?”

GOLDEN CHILD

The name Goldenvoice may not immediately ring a bell for those outside the music business. However, most music fans know of Coachellawhich is put on by Goldenvoice’s parent, AEG.

In January 2017, an anti-Coachella movement began to take off online, following reports about AEG owner Phil Anschutz’s political donations.

“Coachella owner Phil Anschutz is an anti-gay GOP supporter and climate [change] denier,” read an Afropunk headline. The Daily Beast soon followed with an article titled, “Your Coachella Money Is Going to a Right-Wing Billionaire Who Funded Anti-LGBT and Anti-Marijuana Causes.”

The headlines were not unfounded. Among the many anti-LGBTQ groups to receive donations from Anschutz, one in particular stood out: the Family Research Council, recognized as an “extremist group” by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

When pressed for comment, Lorway was quick to dismiss the issue.

“From what I understand, this seems to be a story that seems to have been written five to seven years ago,” he says. “His foundation made some gifts to an anti-LGBT organization, but he has since clarified, and there’s been no future stories.”

Anschutz issued a statement distancing himself from “anti-LGBTQ initiatives” and last year donated $1 million to support the Elton John AIDS Foundation LGBT Fund. In 2018, Anschutz and his various entities also donated more than $348,000 to Republican state committees, conservative PACs and individual Republican politicians. Included in the recipients’ list were Georgia Sen. David Perdue, an active supporter of Trump’s transgender military ban, and Colorado Sen. Scott Tipton, described in Colorado’s Durango Herald as “a proven enemy of LGBTQ rights.”

“While he’s still donating to conservative causes and candidates, he’s not boosting organizations that openly describe homosexuality as a ‘Satanic perversion,’ like he used to,” the entertainment site MXDWN reported in January.

The heir to a large oil and gas empire, Anschutz is a close friend of President Trump appointee Neil Gorsuch. In 2004, Gorsuch helped Anschutz drain $368 million out of Regal Cinemas, a company whose stock was a primary source of funds for the Teachers’ Retirement System of Louisiana. Two years later, Anschultz wrote to George W. Bush, imploring the Republican president to put his friend on the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals. It was there that Gorsuch was presiding when he was tapped by Trump for the Supreme Court.

Though Stanford Live was blasé on the subject, the school’s student body was vocally opposed to the deal with AEG. In an email, Associated Students of Stanford University President Sharta Kantipamula wrote:

“The actions undertaken by AEG’s CEO are incredibly harmful to the LGBTQ community and are antithetical to the ASSU’s and greater Stanford community’s values. Therefore, we denounce these actions in the strongest terms. We were not previously aware of the relationship between Goldenvoice, AEG and Stanford Live. With this knowledge, we call on Stanford Live to reaffirm their values and commitment to diversity and inclusion and denounce these harmful actions. We also call on Stanford Live to re-evaluate all existing and future contracts to ensure that they are partnering with organizations that share our values.”

END OF HISTORY

That Stanford would partner with such a controversial entity might surprise some, but the school is no stranger to controversy. This March, Stanford was one of many institutions to be implicated in the college admissions scandal, wherein wealthy parents paid to have their kids admitted under false athletic pretenses. As a result, white-collar applicants around the Bay Area are now looking at prison time. Quick to distance itself from the scandal, Stanford expelled a student involved and fired head sailing coach John Vandemoer.

But, far from an outlier, accusations of this type have been following the school for almost 100 years. Way back in 1928, Upton Sinclair, author of Oil! and The Jungle, took the school’s athletic program under the microscope, writing, “Everything depends on victory, and to make certain of victory, there are professional coaches. … The alumni have raised a ‘yellow dog’ fund to bring in professional athletes. … A Stanford professor assured me that many of them did not even bother to get textbooks.”

In another controversy that broke recently, Stanford announced, to wide outrage, that it would cease funding the 125-year-old Stanford Press. The reason cited: “budgetary restrictions.” This despite the fact that the academic publisher brings in $5 million in book sales a year, and despite the school’s existing endowment of more than $26 billion. In a statement quoted in Inside Higher Ed, David Palumbo-Liu, a Stanford professor and one of the founding voices of the Asian-American literary movement, denounced the decision, calling it “irresponsible and shameful.”

In the ’80s, the school also came under fire from students and faculty for its sponsorship of the right wing think tank, the Hoover Institute. An article published in Stanford Magazine showed that at the time, there was only one registered Democrat among Hoover fellows, which included Reaganomics architect Jack Kemp and hydrogen bomb theoretical physicist Edward Teller.

Buried within lists of board members, internal publications and industry-specific journalism, there is at least one demonstrable link between Stanford, Hoover and AEG: Hoover overseer Scott Brittingham and AEG VP Moss Jacobs previously served on the same board together at the Santa Barbara County Bowl. There, in 2016, Jacobs engineered a business deal between the Bowl and AEG which one outlet called “Machiavellian,” a procedural ruse in which he quit the Bowl to begin working with AEG, then organized a deal between the Bowl and AEG, ousting its previous promoter.

Director emeritus of the Santa Barbara County Bowl, Brittingham joined Hoover’s board of overseers in 2012. A noted Grateful Dead fan, Brittingham commissioned a sculpture of Jerry Garcia’s right hand to be displayed at the Bowl and donated $500,000 to UCSC for an exhibit space of Grateful Dead archival materials.

Requests for clarification on Brittingham’s current role at the Hoover Institute went unanswered. An empty page bearing Brittingham’s name appears on the Institute’s website as of this writing.

ALL OVER NOW

About a year ago, KQED writer Sam Lefebvre began to notice a major change taking place in San Francisco.

“It really caught my attention when the partnership between Goldenvoice and Great American-Slim’s was announced,” he says. “For as long as Slim’s has been around, and certainly for decades with the Great American, these had been flagship independent music venues in San Francisco.”

By that time, Goldenvoice had already been operating in the city for a decade. It had begun reasonably enough, with the Warfield and the Regency Ballroom, two of the city’s biggest rooms. But now, with the 500-capacity Slim’s and the 600-capacity Great American Music Hall under their control, Goldenvoice had established a foothold at nearly every level of booking in the city.

“It sort of brought it to the point where it began to seem like a threat to independent music venues in the Bay Area,” Lefebvre says.

With Frost in its control, one of the industry’s largest players is now creeping southward, consolidating power in a business once defined by dreamers and outsiders. “I mean, if you look at the ownership of any major company these days, there are going to be things that aren’t aligned with your personal politics,” says Lorway, Stanford Live’s executive director.

That is, if nothing else, a pragmatic view.

Back on Oct. 10, 1982, as the sky went dark and night wore on, the Dead settled into their final song, Bob Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.”

“Forget the dead you left, they will not follow you,” Garcia sang, before his final words of the night: “It’s all over now, baby blue.”

After a moment’s silence, Graham took the stage again.

“There are some plastic bags out there,” he says, at night’s end. “If you can, take some of your leftovers with you so we can clean this up. Hope to god they like us, and we’ll be back here sometime next year, hopefully.”

A crowd member, caught on the bootleg recording, answers back:

“Hopefully.”